Yvonne Aiken has been able to keep her rent affordable despite living in one of the most expensive areas in the country.

For the past five years, she has lived in Arlington Mill Residences in Arlington County, where she pays less than $1,800 a month for a two-bedroom apartment in an area where the monthly rent at a comparable property averages $2,387.

Aiken, a project coordinator and executive assistant, says it would be difficult to live in Arlington if she had to pay going rates. But Aiken’s apartment is unusual. Arlington Mill Residences are owned by nonprofit developer Arlington Partnership for Affordable Housing. The complex represents one example of the efforts local officials and nonprofits are making in Virginia to create less expensive housing.

“Affordable housing is keeping rent at a rate that we can afford based on our income,” Aiken explains, which typically means devoting no more than 30 percent of a household’s income toward rent.

Amazon’s impact

The scarcity of affordable housing is not a new issue in Virginia, but it’s become a hot topic since Amazon announced plans to locate half of its second headquarters, known as HQ2, in Arlington and Alexandria. The move will bring $2.5 billion in investment to the area and 25,000 jobs over 12 years paying annual salaries averaging $150,000.

The project also is expected to attract more people to a region that lacks enough affordable housing. The number of affordable units in Arlington and Alexandria has fallen dramatically in recent years despite efforts to boost the number of apartments reserved for lower- and middle-income tenants.

“We’re seeing a rapid disappearance of what we call market affordable housing,” says Nina Janopaul, CEO of the Arlington Partnership for Affordable Housing. “The older apartment complexes that used to be affordable to middle- and lower-income folks are now being gentrified and upgraded.”

In Alexandria, only 7 percent of privately owned apartment buildings were considered affordable to families earning 60 percent of the area’s median income, which stood at $117,200 last year.

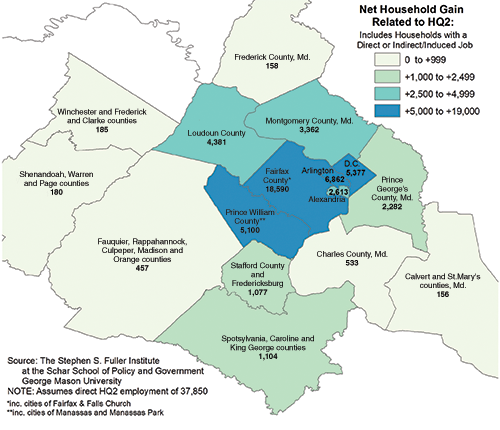

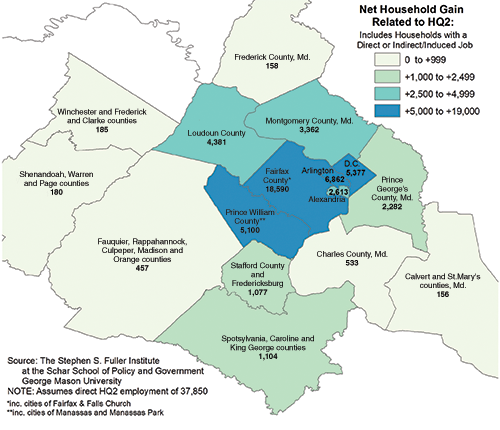

A report by the Arlington-based Stephen S. Fuller Institute at George Mason University says Amazon’s arrival will have minimal impact on the region’s housing stock and affordability.

A report by the Arlington-based Stephen S. Fuller Institute at George Mason University says Amazon’s arrival will have minimal impact on the region’s housing stock and affordability.

The tech giant’s move likely will raise home sales and rental prices but only slightly above increases that would occur if it didn’t locate in the region, according to the study.

Amazon’s presence will boost housing demand, the report says, but that increase will be gradual and many of the company workers will settle throughout the region instead of concentrating in one area.

These projections, however, are irrelevant because the affordable housing problem already exists, says Michelle McDonough Winters, executive director for the nonprofit Alliance for Housing Solutions, which works to increase the supply of affordable housing in Northern Virginia.

“It’s going to add to the demand, so we need to add to our supply and … our policy toolbox to address these issues,” she says.

In connection with the Amazon announcement, the Virginia Housing Development Authority has pledged to provide an additional $15 million per year to the region for affordable workforce housing. Details on how the money will be used and distributed are still in the works.

Alexandria expects to spend at least $8 million annually on affordable housing during the next 10 years. About $1 million of that amount will be earmarked to meet housing needs created by Amazon. Arlington, meanwhile, expects to allocate about $7 million per year on affordable projects in the neighborhoods near Amazon’s headquarters.

David Cristeal, director of Arlington’s housing division, is confident the county will be able to accommodate the influx of new Amazon workers, but he also believes they will put pressure on housing prices.

“That’s been happening anyway,” he says. “I don’t think Amazon coming here is going to change the direction of where we’re going.”

Arlington continues to look for creative ways to increase its housing stock, Cristeal says. For example, his division plans to recommend that the county board adopt an ordinance allowing property owners to build small, detached residences on their properties. (Think of a small cottage for grandma.)

Current law allows a small living space, such as a basement apartment, to be created from an existing structure but does not allow new buildings on the same property.

Future strategies also could include allowing two 2,000-square-foot houses to be built where one 4,000-square-foot structure once stood. “Theoretically, that would make one home half the price and be expanding affordability,” Cristeal says.

Officials also are keeping a close eye on properties that originally were built as affordable housing but have completed the compliance period required for keeping rents below market rate. These properties often are sold to the highest bidder and upgraded to command higher rents. Virginia localities are working with VHDA to find ways to keep these properties affordable.

Localities and nonprofit developers also are helping turn unconventional properties into housing. The Arlington Partnership for Affordable Housing, for example, bought the American Legion Post building on Washington Boulevard, hoping to turn it into 160 affordable housing apartments. The bottom floor will serve as the new headquarters for the American Legion Post 139, and veterans will be given preference in renting the apartments. The partnership hopes to secure funding and permits for the project by June and start construction next year.

In Alexandria, AHC Inc., a nonprofit developer, is working with the Episcopal Church of the Resurrection in the city’s Beauregard neighborhood to convert it into 113 affordable apartments and a new church building. Construction should begin this year and be finished by 2021.

Affordability in other areas

Amazon’s headquarters project has shined a spotlight on housing issues in Northern Virginia, but lower- and middle-income families throughout the commonwealth face problems finding affordable places to live.

A state-commissioned report found that one in three Virginia households in the state in 2015 were spending more than 30 percent of their income on rent or mortgage payments. In response, Gov. Ralph Northam has proposed adding $19 million in the current two-year budget to address housing issues.

The report found that affordability problems were most acute in Hampton Roads, where 52 percent of renters spent more than 30 percent of their income for housing, followed by Richmond (47 percent) and Northern Virginia (44 percent).

In fact, eviction rates in Richmond and Hampton Roads are among the highest in the country, according to a 2016 analysis by the Eviction Lab at Princeton University. In Richmond, 11.4 per 100 renter homes were evicted that year, giving it an eviction rate of 11.4 percent. (No. 2 among the nation’s larger cities). Hampton, Newport News, Norfolk and Chesapeake also ranked among the top 10 with eviction rates ranging from nearly 8 percent in Chesapeake to almost 10.5 percent in Hampton.

During the past decade, Richmond has attracted a wave of new residents and private investment, leading to the redevelopment of many long-neglected parts of the city. Rising rents, however, have been blamed for pushing out lower-income residents.

The Better Housing Coalition, a Richmond nonprofit, wants to ensure people with modest incomes have access to high-quality housing. “Long-term residents that have been in a community when it was struggling want the opportunity to stay when the community gets better,” says Greta J. Harris, the group’s president and CEO.

Harris was co-chair of a housing task force appointed by Richmond Mayor Levar Stoney. The group’s mission has morphed into a bigger project, examining housing affordability issues throughout Central Virginia. Richmond and Chesterfield, Henrico and Hanover counties are working with the nonprofit Partnership for Housing Affordability to orchestrate a regional strategy. The group hopes that by the end of this year the localities will have a framework for tackling affordable housing issues individually and collectively.

Regional cooperation would be helpful, for example, if localities wanted to implement “mandated inclusionary zoning,” which is in place in some areas of Northern Virginia.

That type of zoning would require developers to designate a portion of their projects for affordable housing in exchange for receiving incentives. Implementing the zoning change would require Virginia General Assembly approval for each locality. Such legislation, supporters believe, would be more likely to pass if requested by a regional group rather one locality.

The Better Housing Coalition also supports implementing property-tax ceilings, which cap the taxes residents pay based on their age, income and the length of time they’ve lived in an area. Harris says the move would allow families to stay in neighborhoods while properties appreciate in value.

These methods may help tackle affordable housing problems, but there is no easy answer, Harris says.

“It’s a long game,” she says. “It’s not something that has a quick fix.”

A report by the Arlington-based Stephen S. Fuller Institute at George Mason University says Amazon’s arrival will have minimal impact on the region’s housing stock and affordability.

A report by the Arlington-based Stephen S. Fuller Institute at George Mason University says Amazon’s arrival will have minimal impact on the region’s housing stock and affordability.