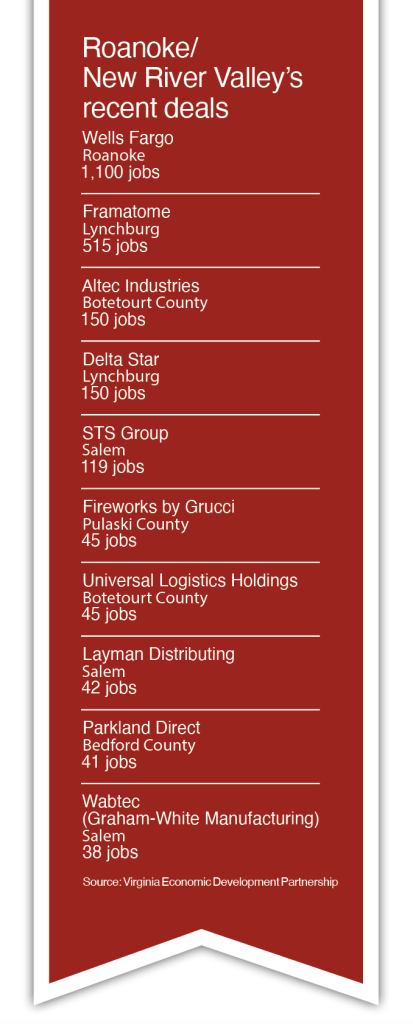

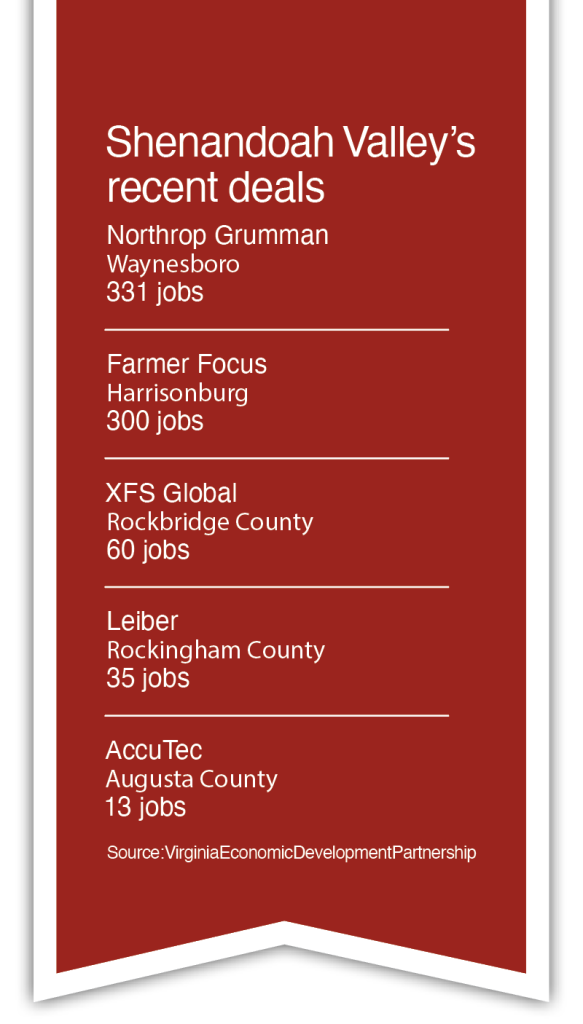

Just a couple years later, an $821,000 site development grant awarded to the Shenandoah Valley Partnership by the state’s GO Virginia economic development initiative has already been paying off, says Jay Langston, the partnership’s executive director.

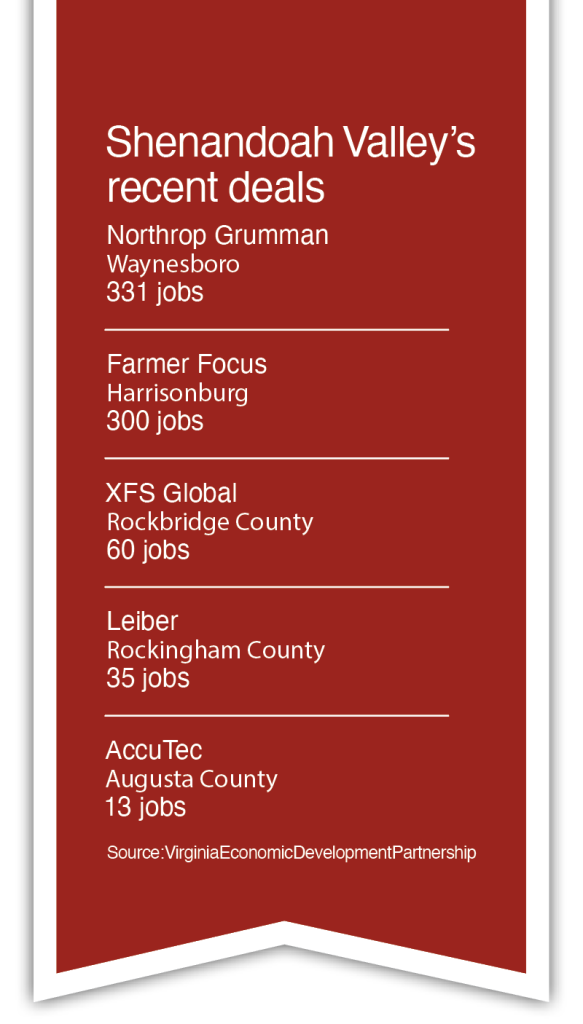

The grant, which paid for work including site evaluation and related environmental reviews and surveys, was focused on improving six regional sites for development. And now, Langston says, two of those sites that the partnership did due diligence on through the 2021 grant are being developed for some of the past year’s biggest economic development announcements — Northrop Grumman’s $200 million advanced electronics manufacturing and testing facility in Waynesboro (see related story) and Leiber’s $19 million plant in Rockingham County.

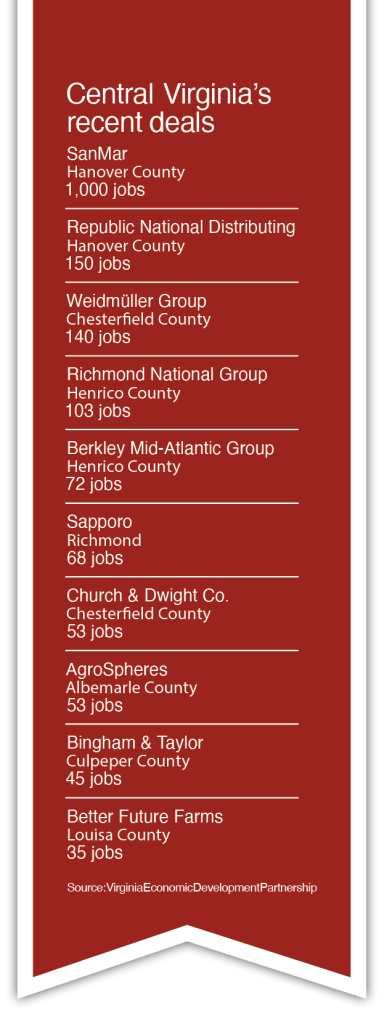

In fact, the Shenandoah Valley saw $339 million in investments announced last year, with plans to create a total of 793 jobs. “We had a good year,” Langston says.

The region was able to diversify its manufacturing base and strengthen its agricultural business environment, Langston says. “While we are led by food and beverage manufacturing, … we are always working to recruit companies.”

Augusta County

Manufacturing and distribution continue to be the largest workforce sectors in Augusta, boosted by the May 2023 opening of a new 1 million-square-foot Amazon.com fulfillment center in Fishersville, creating 500 jobs. Amazon has opened more than 30 fulfillment and sorting centers and delivery stations in Virginia since 2006.

Speaking at a ribbon-cutting for the center, Augusta County Administrator Tim Fitzgerald said, “It is a testament to making economic development a strategic priority for the county.”

Additionally, early this year, Washington, D.C.-based fast-casual Mediterranean restaurant chain CAVA was poised to open its $30 million, 57,000-square-foot processing and packaging facility at Mill Place Commerce Park in Verona, a project expected to create more than 50 jobs.

“All in all, 2023 was a stable year with some steady growth,” says Rebekah Castle, the county’s director of economic development and marketing.

Culpeper County

Culpeper is carving out a niche in data centers. A pair of rezonings in the town and county paves the way for Peterson Cos. to build a 150-acre, 2 million-square-foot data center campus along McDevitt Drive and East Chandler Street. Additionally, cloudHQ has acquired 116 acres along the same corridor with reported plans for the similarly sized Copper Ridge Data Center Campus.

“In the last two years, we’ve added about 10 million square feet of data space,” says Bryan Rothamel, the county’s director of economic development.

Frederick County

Frederick County

In Frederick, developers are seeking tenants for two large spec industrial parks.

Colliers is marketing One Logistics Park, a $150 million, 2.7 million-square-foot industrial complex being developed by The Meridian Group and Wickshire Group just outside Winchester. Meanwhile, Peterson Cos. is promoting its Valley Innovation Park, a 145-acre industrial park near Interstate 81, which has the potential to house nearly 2 million square feet of manufacturing, industrial and life science facilities.

“The property is already graded. Having large sites project-ready … will give us good options to be competitive,” says Patrick Barker, executive director of the Frederick County Economic Development Authority.

In other county economic development news, packaging manufacturer Monoflo International announced in September 2023 the completion of its new 325,000-square-foot warehouse facility on the border with Winchester. Additionally, ZM Sheet Metal, an HVAC steel component manufacturer, announced plans to expand in Frederick. ZM purchased 23 acres in Stonewall Industrial Park and plans to start construction on a new 160,000-square-foot manufacturing facility in the second quarter of 2024. The company says the facility will be able to accommodate 300 workers.

Harrisonburg

Farmer Focus, which handles processing, packaging and sales of poultry products for about 100 regional farmers, embarked on a $17.8 million expansion of its Harrisonburg processing plant last year, aided by a $3.6 million U.S. Department of Agriculture grant. The company plans to add 300 jobs by 2025.

“Farmer Focus was a startup in 2014 and has now surpassed 1,000 employees and has become our largest private sector employer in the city,” says Brian Shull, Harrisonburg’s economic development director.

In September 2023, Montebello Packaging, a manufacturer serving the pharmaceutical and cosmetic industries, announced a $12 million expansion with a new production line.

Additionally, Staunton Innovation Hub co-founder Peter Denbigh is renovating the historic Wetsel Seed Complex in downtown Harrisonburg into the $4.5 million Harrisonburg Innovation Hub, scheduled to open by the end of this year.

Page County

Luray RV Resort on Shenandoah River, previously Outlanders River Camp, opened in August 2023 following a $30 million expansion by its new owner, Blue Water. Campsites increased from 73 to 350.

Rockingham County

“We like focusing on the food and beverage industry because of our agricultural base. It is what comes naturally for our community,” says Joshua Gooden, the county’s economic development and tourism coordinator.

In September 2023, Leiber, a German manufacturer that processes brewers’ yeast into animal nutrition, biotechnology and nutraceutical products, announced it would invest up to $20 million to establish its first U.S. manufacturing facility in the county’s Innovation Village. It’s expected to create 35 jobs, with plans to open by late 2025.

Also, Veronesi Holding, an Italian cured meats producer, opened its first U.S. production operation for its Negroni deli meats brand in the Innovation Village at Rockingham. The nearly $100 million project broke ground in 2022 and plans to hire more than 150 workers. Currently, the company has 50 employees there.

Among the most anticipated county economic development projects underway is Virginia’s first Buc-ee’s travel center. The Texas-based convenience store chain broke ground on the project in January during a ceremony attended by Gov. Glenn Youngkin and Buc-ee’s founder and CEO Arch “Beaver” Aplin III.

Located at the intersection of Interstate 81 and Friedens Church Road, the 74,000-square-foot center will include 120 fueling positions. Buc-ee’s expects construction to take about 17 months, according to a spokesperson, and it plans to hire more than 200 workers.

Shenandoah County

Shenandoah County continues to see growth in tourism and investment in the downtown Mount Jackson area with retail shops and restaurants.

Alexandria-based Logan Food is investing $15 million to build a meat-processing facility, with plans to add up to 60 jobs. It’s expected to open in 2025, according to Jenna French, the county’s director of economic development.

Warren County

Last year, Warren County had success with industrial and commercial economic development as well as “re-engaging with the small business market,” says Joe Petty, the county’s director of economic development and tourism.

Nature’s Touch Frozen Foods moved into its new 126,000-square-foot, $40.3 million facility, adding more than 70 employees.

And the Port of Virginia’s Virginia Inland Port (VIP) is partnering with the Virginia Department of Transportation to construct a bridge over the Norfolk Southern Railway on Route 658. The $20 million-plus project is funded by a U.S. Department of Transportation grant and scheduled for completion in 2025.

“This is a huge capital improvement project that will add rail capacity for VIP and, ultimately, uninterrupted access for the community,” says Petty.

Waynesboro

“I’m very pleased with this past year,” says Greg Hitchin, the city’s director of economic development and tourism. “We’ve had a lot of success on different fronts.”

The city landed the largest deal in the region with global aerospace and defense technology company, Northrop Grumman, investing more than $200 million to build a new advanced electronic manufacturing and testing facility, which plans to hire more than 300 workers over the next five years.

Additionally, Innovation Management, which manages the Staunton Innovation Hub, is opening a 6,000-square-foot innovation hub in Waynesboro in spring 2024 in the former Virginia MetalCrafters building. The hub will provide coworking space, private offices and conference rooms.

“It’s really gratifying to see the reuse of an historic building,” Hitchin says.