Reaching the “major league” in academic research boosts Old Dominion University‘s clout in attracting top talent and grants, emphasizes the university’s vice president for research.

Achieving the R1 research classification “enhances the reputation of the university,” says Morris Foster, and “helps in the talent [recruitment] area … [because] some students will only go to an R1 school, [and] some faculty will only work at an R1 school.”

In December 2021, the Norfolk-based research university joined the ranks of 146 U.S. four-year institutions that have earned Research 1 classification, the top research ranking awarded by the Carnegie Classification of Institutions of Higher Education. To qualify for the designation, the university had to meet benchmarks in 10 areas, including number of research doctorates awarded, total research expenditures, aggregate level of research activity and number of research staff. Four other Virginia universities — George Mason University, the University of Virginia, Virginia Commonwealth University and Virginia Tech — have R1 status.

Having R1 status also provides an “intangible benefit’ when applying for research grants, according to Foster. “It helps to be seen in that big league. It’s recognized at the international level.”

ODU, with more than 18,300 undergraduates and 4,600 graduate students, is “a comprehensive university,” Foster says, with seven major colleges and schools: the College of Arts and Letters; the Strome College of Business; the Darden College of Education and Professional Studies; the Frank Batten College of Engineering and Technology; the College of Health Sciences; the College of Sciences; and the School of Cybersecurity. Additionally, Eastern Virginia Medical School is expected to merge into ODU as of Jan. 1, 2024, which would include medical, nursing and public health schools. ODU is also working to establish a new School of Supply Chain, Logistics, and Maritime Operations, as well as a School of Data Science.

‘Stamp of approval’

Kevin Leslie, ODU’s associate vice president for innovation and commercialization, calls the R1 classification “a lagging indicator. … It’s a public acknowledgment of what we already know internally that we can do. This is a stamp, a seal.”

So far, Leslie says, there isn’t enough data to determine how the R1 designation has helped attract faculty, students and industry partners, but “it gives people one more reason to attend or be employed here. It shows you have sustainable opportunity” at a time when “everybody is competing for doctoral students.”

Foster and Leslie note that ODU is already known for its strong maritime research, and the school has received recognition for its business, education, engineering, nursing, career development and cybersecurity programs. The university has longstanding collaborations with NASA, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and the U.S. Department of Energy’s Thomas Jefferson National Accelerator Facility (Jefferson Lab).

New growth areas for ODU, Leslie notes, include data science and biomedical and health research.

ODU’s proximity to the Port of Virginia makes it an ideal place to conduct wide-ranging maritime-related research, according to Foster, covering “everything from resilience to supply chain to oceanography. A large percentage of our graduates go into jobs in maritime — shipbuilding, shipping activities, the military.”

ODU’s associate vice president for maritime initiatives, Elspeth McMahon, believes the university’s R1 designation helps make it even more marketable in the region, especially when working with federal entities like the Navy and Coast Guard. She calls the designation “a huge win for the university. There’s so much opportunity. It’s been a whirlwind.”

McMahon coordinates ODU’s extensive and varied programs related to the maritime industry. That includes being involved with the university’s Virginia Modeling, Analysis, and Simulation Center (VMASC), a multidisciplinary applied research and enterprise research facility in Suffolk. Two entities there have a maritime focus: One is the Virginia Digital Shipbuilding Program (VDSP), which conducts applied interdisciplinary research and development to speed the adoption of digital innovations in the industry. The other is the Maritime Industrial Base Ecosystem (MIBE), which works to strengthen the Hampton Roads economy through collaboration among the region’s business, academic and government partners.

Helping train a skilled workforce is a key part of that mission, according to McMahon. To attract future maritime workers, “we create programs for high schools and middle schools. We use virtual reality to show what maritime skills are.” In return, “we receive a great amount of support from the industry.”

She also works to promote maritime career awareness among graduate and undergraduate students in ODU’s Batten College of Engineering and Technology.

One of the university’s newest ventures is the School of Supply Chain, Logistics, and Maritime Operations, which is awaiting approval from the State Council of Higher Education for Virginia (SCHEV). The school’s approach will be interdisciplinary, “with a maritime flavor,” McMahon says. “Maritime corporations in Hampton Roads need people in IT, HR, logistics, operations, cybersecurity.”

Last year, ODU co-hosted OCEANS, a biannual conference for global marine technologists, engineers, students, government officials, lawyers and advocates, co-sponsored by the Marine Technology Society and the IEEE Oceanic Engineering Society.

It’s just another example, says McMahon, of how “ODU is really getting out there nationally and internationally. This puts us on the map as a maritime-centered university.”

Applied research

Tom Allen, an ODU professor of political science and geography, also says that while the R1 designation is “an acknowledgement, a recognition, of the volume and the quality” of research being conducted at the university, it also provides an advantage when he and fellow researchers submit grant proposals to agencies such as the National Science Foundation.

Allen’s research focuses on coastal resilience and rising sea levels. ODU’s waterfront campus in the coastal city of Norfolk makes it an ideal laboratory for research on flooding and climate change. In March, the Virginia Institute of Marine Science (VIMS) reported that Norfolk had the highest rate of relative sea-level rise on the East Coast for the fifth year in a row.

Allen leads the climate and sea level rise program at ODU’s Institute for Coastal Adaptation and Resilience (ODU-ICAR), which partners with cities, businesses, nonprofits and rural communities to test out practical applications for university research.

“We approach with broad and deep technology,” he says. “We have street sensors that predict flooding impacts. Drones are being used to map some of the problems better. We work with autonomous systems vessels that are operated remotely.”

The program is using a dense network of sensors and computer models to monitor the impact of rising sea levels on wetlands in Hampton Roads.

And with funding from a $1.2 million NASA grant, Allen and his fellow ODU researchers are harnessing artificial intelligence to construct a digital replica of the Hampton Roads area — complete with buildings, homes and a transportation network — for modeling sea level rise. “The focus of our digital plan is on people and flooding,” he notes, but he says the model also could be used for other types of research projects.

The goal is to “bring things together and see the future,” he says. “What if something like Hurricane Isabel happened again? We could predict the impact and then go back–

wards and work with planners and say, ‘What might we need to change for a better outcome?’”

Not all their coastal resiliency efforts are high-tech, though.

For instance, to help protect area wetlands, ODU is planting tidal marshes, echoing a federal approach used in the Gulf of Mexico. “If we lose wetlands,” Allen says, “there’s the risk of a ripple effect on fisheries, beaches, water quality and tourism.”

Additionally, each year, during the highest tide of the year, ODU faculty, staff and student volunteers use blue flags, eco-friendly paint and chalk lines to take data and project future high tides. The “Blue Line Project” is a collaboration between ODU, Norfolk and NOAA.

‘Icing on the cake’

One of the next big steps for ODU, Foster notes, is its planned integration of Eastern Virginia Medical School. “It would be a significant transformation to add a medical school campus and a chance to grow our population health studies,” he says.

For Leslie, ODU’s “next stage” involves improved efforts to advance biomedical research from the lab to the marketplace.

“We want to coordinate better as a whole. We want to support things from start to finish,” says Leslie, who previously was executive director of the Hampton Roads Biomedical Research Consortium before this year joining ODU, where he oversees marketing and commercialization of staff and student research.

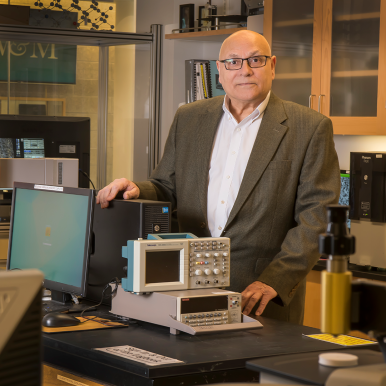

Gymama Slaughter, executive director of ODU’s Center for Bioelectronics, points out that the university has a long list of biomedical research projects in the pipeline. “We’re looking at targeted drug delivery that would enable the body to kill cancer. There’s biofabrication, the printing of organs. We’re collaborating on triple-negative breast cancer research. We’re looking at what prevents wounds from healing,” she says. The goal is to “propel research that we can take all the way to consumers.”

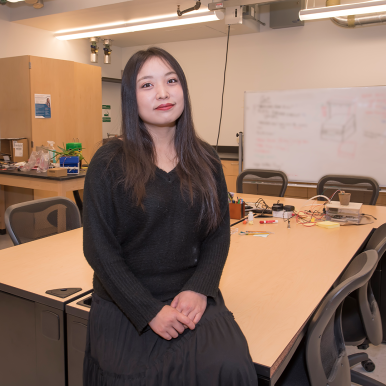

Slaughter, who was already on ODU’s faculty when it received the R1 designation, says she joined ODU “because of the tremendous amount of resources available to underrepresented groups,” such as ODU’s Graduate Research Training Initiative for Student Enhancement (G-RISE), a program designed to boost diversity among Ph.D. candidates in biomedical-related disciplines.

G-RISE is funded by a National Institute of Health NIGMS grant; it accepted its first cohort in May 2021. Among the benefits of G-RISE are a 6-week summer doctoral bridge program, internships at biotechnology companies and government national laboratories, and academic and social workshops.

Now, “being R1, we have the visibility” to put even more resources into recruiting and providing benefits for underrepresented groups, says Slaughter. “We have done a tremendous amount of work to get us here. Now people recognize us and the research that happens here. It’s an historic moment.”

One doctoral student in the G-RISE program is Erem Ujah, who is studying biomedical engineering and recently co-published a journal article on an “ultrasensitive tapered optical fiber refractive index glucose sensor” designed to detect early prostate cancer.

As an R1 research institution, “our research will be seen more, and we’ll be able to continue” working toward their long-term goal of extending life expectancies for prostate cancer patients, Ujah says, adding that the designation “puts us on the status of Johns Hopkins or Massachusetts Institute of Technology.”

Alexander Hunt, another G-RISE scholar who also is researching early prostate cancer detection, says ODU researchers are now working with human samples “to see if these devices will actually work. We’re working on being able to take the test at home. The end goal is to commercialize it.”

Hunt earned his undergraduate degree from ODU and was acting on Slaughter’s recommendation to pursue a Ph.D. when ODU landed the coveted research designation.

“I already knew what the university had to offer,” he says. “R1 was the icing on the cake.”

At a glance

Founded

Old Dominion University was founded in 1930 as a two-year college to train teachers and engineers as an extension of William & Mary and Virginia Tech. It gained independence in 1962 as Old Dominion College and began offering master’s degrees in 1964 and doctoral degrees in 1971. It was renamed Old Dominion University in 1969.

Campus

ODU has seven major academic colleges and schools. Its 337-acre Norfolk campus is bordered on two sides by the Elizabeth and Lafayette rivers. The school also operates regional higher education centers in Virginia Beach, Portsmouth and Hampton.

Enrollment1

Undergraduate: 18,363

Graduate: 4,656

In-state: 20,178

International: 717

Students of color: 11,5902

Employees

1,595 instructional faculty;

3,405 total employees

Tuition and fees

In-state undergraduate tuition and fees: $12,262

Out-of-state undergraduate tuition and fees: $32,662

Room and board: $14,652

Average financial aid awarded to full-time freshmen seeking assistance: $15,987

1 Fall 2022 enrollment statistics | 2 2021-22 data | 3 2023-24 rates