‘Behind the eight ball’

Officials rush to correct looming site shortage

‘Behind the eight ball’

Officials rush to correct looming site shortage

David Manley had a good feeling. The site visit was going well.

During their spring 2021 tour of the Progress Park industrial site in Wytheville, the leaders of a manufacturer of nitrile gloves — those blue, disposable pieces of personal protective equipment that have become ubiquitous during the pandemic — seemed intrigued by the prospect of the location serving as the future home of their factory, which would bring with it 2,500 jobs.

During that visit, “their eyes essentially lit up,” recalls Manley, executive director of the Joint Industrial Authority of Wythe County in Southwest Virginia.

With a graded site, a rail hub, utilities and telecom infrastructure ready to go, the location clearly appealed to the glove execs. The county had begun work on the 233-acre parcel in the 1990s. Over the years, with support from the county, the state Tobacco Region Revitalization Commission and others, about 165 of its acres had been graded and infrastructure put in place.

But would it be enough?

Room for improvement

If you build it, they will come — that has long been the driving philosophy of site development, the work done by economic development agencies and authorities to identify and prepare industrial sites for future businesses.

But lately in Virginia that mantra has shifted. Business leaders have become increasingly concerned that if they don’t build it, businesses will go elsewhere.

Since 2016, Virginia missed out on more than 42,000 jobs and $75 billion in capital expenditures because companies were unable to find acceptable ready-to-build locations in the commonwealth, according to a September 2021 analysis by the Virginia Economic Development Partnership, the state’s economic development arm.

![“Until recently, [Virginia] just didn't invest in sites,” says Chris Lloyd, chairman of the national Site Selectors Guild and a senior vice president with McGuireWoods Consulting. The current site shortage, he says, “has been 30 years in the making.” Photo by Rick DeBerry Photo by Rick DeBerry](https://virginiabusiness.com/wp-content/blogs.dir/1/files/1/2022/02/DSC_0013-copy-386x386.jpg)

Those losses have come despite Virginia’s business-friendly reputation and high marks on metrics such as governmental support for business, not to mention its world-class seaport, well-educated workforce and desirable mid-Atlantic location.

“Virginia has been pretty heavily underperforming on the bigger projects,” says Stephen Moret, who was VEDP‘s president and CEO from 2017 through the end of 2021 and played a key role in Wythe County landing the Blue Star NBR LLC nitrile glove factory last year. “And the vast majority of the time the biggest factor has been the lack of a well-prepared site.”

One recent example: a $5.6 billion Ford Motor Co. factory with 5,600 jobs. Ford decided against building in Virginia — largely, Moret says, because Virginia didn’t have a site ready to go within the company’s timeline. In September 2021, Ford announced it would open the plant near Memphis, Tennessee.

The issue, Moret and others in Virginia economic development say, is a historic lack of funding for site development in the commonwealth. That has left Virginia lagging other states in the current era of high-speed business decision-making, a point emphasized by Virginia’s new governor, Glenn Youngkin, while on the campaign trail.

“Until recently, [Virginia] just didn’t invest in sites,” says Chris Lloyd, a senior vice president and director of infrastructure and economic development at McGuireWoods Consulting LLC who serves as chairman for the national Site Selectors Guild. The situation, he adds, “has been 30 years in the making.”

Shovel-ready shortage

Virginia has a few structural disadvantages when it comes to landing coveted large-scale industrial projects like multibillion-dollar chip factories, Lloyd says. One is Virginia’s unique governmental structure in which cities and counties, by law, are independently governed. This can create a disincentive for, say, a county government to partner on a development project in a neighboring city for which it would not see any direct tax benefit. Another impediment is the way Virginia’s utilities regulation can discourage investment in projects that do not have a clear, foreseeable outcome.

But those hurdles can be overcome, Lloyd says. A little-noticed aspect of the state law governing economic development authorities — the Virginia Regional Industrial Facilities Act — allows them essentially to set up revenue-sharing agreements, for example.

More significant has been Virginia’s historic lack of urgency around the issue, say Lloyd and others. Virginia has luxuriated in a healthy tax base and heavy federal spending in Northern Virginia and Hampton Roads, and in the past few decades, the work of luring large factories seemed less than critical.

But in recent years that attitude has changed as, one after another, companies planning large industrial projects have surveyed Virginia and found it lacking.

In the past five years, Virginia has ranked ninth out of 11 states in the South — ahead of only West Virginia and Maryland — in the number of manufacturing jobs from “greenfield” construction projects (those built on previously undeveloped land), VEDP found in a recent internal analysis.

Since 2015, of the 81 new industrial projects in the Southeast United States that required 250 acres or more, Virginia has won exactly zero, according to VEDP. Those projects generated more than $22 billion in capital expenditures and an estimated 38,000 jobs; North Carolina won seven of them, totaling more than $1.4 billion in investments and creating 5,600 jobs.

The situation is largely because of Virginia’s shortage of shovel-ready, large-scale industrial sites, say development experts. Between 2018 and 2021, large projects requiring 250 acres or more comprised 15% of companies’ site-search requests in Virginia, but 51% of total jobs and 78% of potential capital expenditures, VEDP found.

Economic development officials are looking to land such large projects because “that’s what really moves the dime,” says Shenandoah Valley Partnership Executive Director Jay Langston. “That is where we’re spending a lot of effort. There are a lot of companies now that are looking for the larger acreage.”

One problem: When Langston’s team looked at 46 sites in its region that might meet that criterion, just two were shovel-ready, with sites prepared and equipped with infrastructure like power and water lines. The rest required years of work.

The issue goes far beyond the Shenandoah Valley, adds Langston, who in 2015 was a lead author on a statewide report drawing attention to Virginia’s looming site shortage. “This is something that we are going to have to work at for probably the next 10 to 20 years, probably beyond my tenure in economic development.”

Megasite investment

The shortage began decades ago. As existing development sites found tenants, Virginia lagged in spending on establishing and preparing new sites.

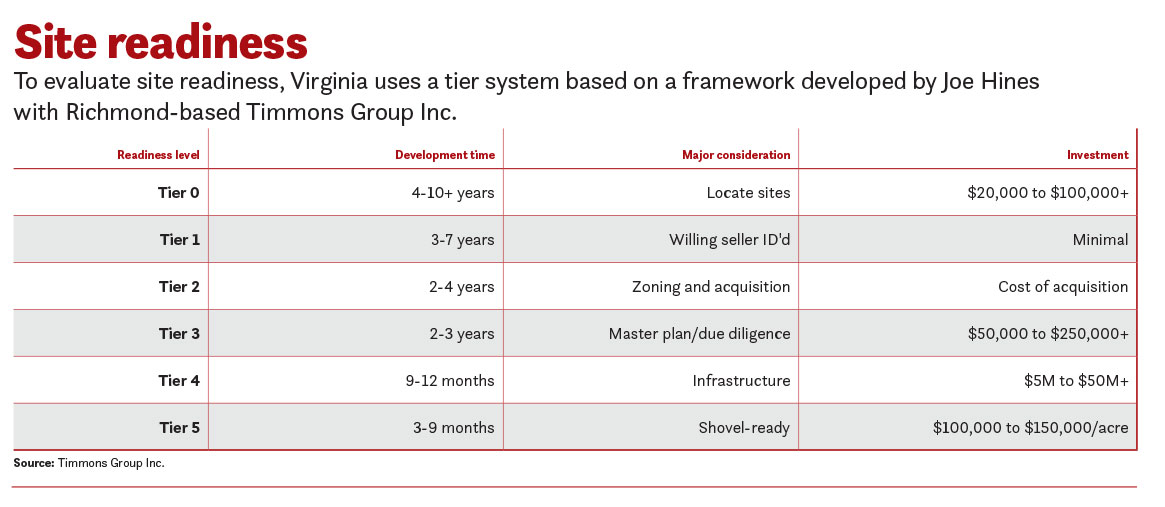

“We all of a sudden found ourselves behind the eight ball,” says Joe Hines, senior principal and director of economic development at Richmond-based engineering firm Timmons Group Inc. “All the smart money had bought up the good dirt.”

Hines, who has worked extensively in site development and analysis, has conducted research indicating that competing states have been spending consistently to develop sites in the past decade, with North Carolina spending up to $100 million and Georgia up to $75 million annually. Virginia, meanwhile, has spent far less, and far less consistently per year, on site development, Hines says.

It takes up to 10 years to ready a site for shovel-ready occupancy, Hines says, which means Virginia will continue to lose projects — including enormous ones, such as the two semiconductor manufacturers currently shopping for homes for their $20 billion, 3,000-plus-employee factories.

And these projects are moving fast. Hines recently took a close look at 11 large development projects in Virginia, South Carolina, Georgia and Alabama totaling $8.5 billion in capital expenditures and 14,725 jobs.

He found that nine of those projects took less than five months from initial contact to a publicly announced deal. The largest of them, a joint venture Mazda-Toyota factory now slated to open near Huntsville, Alabama, comprises $1.6 billion in capital expenditure and 4,000 jobs. That project moved from first contact to final deal in five months.

State officials have taken notice. In January, at the end of his term, Gov. Ralph Northam announced $7 million in state grants to support development of sites larger than 100 acres across Virginia.

More dramatically, Northam’s proposed state budget included $150 million to support site development. That figure matched VEDP’s 2021 recommendations: $100 million toward developing “megasites” of 250-plus acres and another $50 million divvied up across the state. The partnership highlighted five megasites across Virginia that would require a total of $118 million to be project-ready on short notice, including a 2,100-acre site in Pittsylvania County and the 1,000-acre Mid-Atlantic Advanced Manufacturing Center in Greensville County.

In all, the partnership said in its unpublished report, this new state expenditure could result in up to 58,000 new jobs and $179 million in state revenue per year.

In an amendment to the 2023-24 biennial budget, Youngkin proposed spending an extra $29 million for site development, plus establishing a $20 million baseline for annual site investment.

On the ground level

While budget talks go on in Richmond, economic development officials are fielding contacts from prospects and wooing potential investors. But they’re fighting to keep pace.

In Virginia Beach, the 35-year-old Corporate Landing Business Park was no more than half developed a few years back. Today, all of it is under construction or under a letter of intent, says Taylor V. Adams, the city’s deputy city manager and director of economic development. A new location, the 155-acre Innovation Park, has all of its 90 developed acres entirely under negotiation or under a letter of intent, Adams adds.

With the upgrades and expansions of developed parcels, “we thought we’d have an inventory,” Adams marvels. “But we found that every time we got a parcel upgraded … we sold it.”

Adams agrees that when opportunity knocks, economic developers have to open the door fast — or lose the sale.

“If your site is shovel-ready, you’ve got a chance,” Adams says. “If it’s not, you’re at the back of the line.”

Back in Wythe County, Manley’s initial optimism was borne out. A few months after that spring 2021 visit, the company — Alexandria-based Blue Star Manufacturing LLC — announced it would build its $714 million factory in the prepared development.

Blue Star NBR’s first manufacturing facility broke ground in January. The first gloves are expected to roll off the line by early 2023.

The romance of Wythe County and Blue Star had been a whirlwind courtship. But it was one that had been decades in the making. By the time Manley showed the site to Blue Star last spring, the deal needed only a relatively small nudge from state coffers in the form of $8 million to upgrade water and wastewater facilities.

The lesson? Be ready, Manley says. “Site readiness is no longer an option. It’s imperative if you want to compete.”

-