Saving shellfish

State agency, Virginia Institute of Marine Science (VIMS), also is part of William & Mary

Saving shellfish

State agency, Virginia Institute of Marine Science (VIMS), also is part of William & Mary

John T. Wells can see from his office when harmful “red tides” are spreading on the York River.

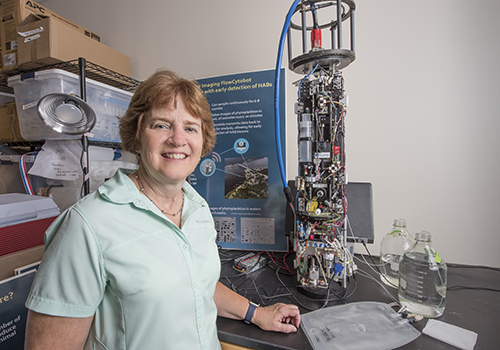

But now researchers at the Virginia Institute of Marine Science (VIMS) are working with a new device known as a cytobot that can detect toxic algal blooms well before the murky reddish threat to marine life is visible. “It offers an early warning that’s going to be a huge benefit to the shellfish industry,” says Wells, dean and director of the institute.

Such research underpins much of what happens at VIMS — it’s the reason shellfish lovers can eat oysters year-round, for one thing. But the institution’s impact runs much deeper. “On the surface, it looks like any other marine science institution,” Wells says.

But VIMS is both an independent state agency and a part of the College of William & Mary, with responsibilities that are mentioned in 36 sections of state code, he says.

Based in Gloucester Point at the mouth of the York River, a major tributary to the Chesapeake Bay, the institute’s triple mission is to research, educate and advise policymakers, industries and the public. “That makes us very unusual as a marine science institution,” Wells says. “Everybody checks that service box — ours is actually mandated and deeply embedded in our operations.”

William & Mary’s new president, Katherine A. Rowe, visited VIMS in August with the university’s board of visitors. By email, she describes the work as crucial to the future of understanding and sustaining marine resources. “It is a rare and wonderful thing to have an advisory arm of the state also serve the dual role as William & Mary’s School of Marine Science,” she says.

Plastic pollution

The institute, which has satellite campuses on the Eastern Shore and Rappahannock River, enrolls about 90 master’s and doctoral students who work closely on research projects with 55 faculty members. “Our students are deeply engaged with faculty researching real-world problems,” Wells says.

They have seen firsthand the tragic consequences of plastic pollution on marine life: In July, an osprey chick had to be euthanized when it became entangled in fishing line brought by a parent to a nest that was being monitored by live-video stream.

Research teams are studying biodegradable plastics to lessen the threat. A new type of cull ring on crab traps, for example, would prevent “lost crab pots from continuing to fish in perpetuity,” Wells says.

The so-called ghost crab pots break away from their buoys and settle on the bottom of the bay, continuing to catch crabs that can’t escape or be harvested. Biodegradable panels provide an escape hatch by slowly dissolving to give captive crabs a way out.

Algal blooms

VIMS research, Wells says, ranges from “global down to molecular in scale.”

Unusually heavy rains during the summer reduced salinity in the York River, keeping toxic algae in check but also slowing several research projects.

Kimberly S. Reece, chair of aquatic health sciences at VIMS, says the cytobots are being programmed to recognize phytoplankton species common to the region.

With current monitoring techniques, it can be days or a week before the blooms are noticed and the species identified, she says.

The goal is to deploy cytobots at strategic spots near shellflish growing areas to more quickly notify growers of HABs, which also can threaten human health.

Clams and oysters

The state now leads the nation in hard clam aquaculture and is second to Washington state in oyster production, he says, and scallop aquaculture could be established soon.

No longer seasonal, oyster and clam aquaculture provides year-round work for people who “are basically farmers, not watermen,” Luckenbach says.

The 2017 “farm gate” value for Virginia shellfish aquaculture was $53.4 million, with sales of $37.5 million for hard clams and $15.9 million for oysters, according to the Virginia Shellfish Aquaculture Situation and Outlook Report.

Clam research, primarily at the Eastern Shore campus, has helped develop techniques to grow and more quickly bring to market the prized little neck clams that are difficult to harvest in large numbers in the wild.

Oyster research was necessitated by disease and habitat destruction that decimated the population.

But the research also led to the development of oysters that are edible through the summer. “We didn’t eat oysters in the summer,” Luckenbach says.

Historically, that was because of bacterial contamination during hotter temperatures. Refrigeration lessened the risk but didn’t solve the taste problem, which results from spring spawning that leaves wild oysters almost flavorless.

That problem was solved through a breeding technique that yielded a sterile oyster. Luckenbach describes the process as something “like growing a seedless watermelon.”

However, he says, the need for continuing research and selective breeding for commercial hatcheries is ongoing and will keep VIMS closely entwined with oyster growers. “You can’t breed a disease-resistant oyster and forget about it for decades,” he says. “The diseases evolve.”

Founded in 1940

VIMS research is funded through more than 300 grant and contract awards worth $20 million in annual expenditures but with a multiyear value of more than $65 million.

The fiscal 2019 operating budget totals $50.3 million, including $22.8 million from the state’s General Fund.

VIMS opened across the river in Yorktown in 1940 as the Virginia Fisheries Laboratory and moved to its current location a decade later. The School of Marine Science opened in 1961.

A William & Mary biology professor, Donald W. Davis, was the institute’s founding father and is the namesake for the newest building on its campus, a $14.4 million, 32,000-square-foot facility dedicated in April.

Davis Hall provides research and office space for five departments, including programs that form the core of the institution’s advisory and outreach education activities.

VIMS was launched with a separation of powers that seems prescient today but actually reflects political sensitivities that existed then as well.

Davis worked with the General Assembly to create the enabling legislation that attempted to ensure that the institute would be immune from political pressure. “He was very clear that the agency that makes marine regulations was not the agency that conducts research that leads to those regulations,” Wells says. “There is a very clear operating separation.”

No hiding in offices

VIMS doesn’t make policy but provides the science that helps state agencies such as the Virginia Marine Resources Commission make regulatory decisions. With its advisory mandate, the institution also assists industry on a range of issues, including determining the impact of dredging plans.

Beach communities can get data from VIMS on offshore resources for sand replenishment projects and learn whether that sand would be compatible with their beach, Wells says.

And the new Commonwealth Center for Recurrent Flooding Resiliency was established in 2016 to provide localities with research and technical support to adapt to sea-level rise.

The center, a joint effort with Old Dominion University and W&M’s Coastal Policy Center, will provide “street-level information” to help with zoning and development plans, he says. “That’s a really big deal,” he says. “If you’re going to build a hospital you want to know where to put it in terms of rising waters over the next 50 years.”

The mission of VIMS to broadly communicate research goes far beyond policymakers and industry, Wells says.

Students, faculty and staff take part in about 360 outreach programs a year that include after-hours lectures, discovery labs, fishing clinics and “Science Under Sail” voyages on the York River.

“We don’t hide in our offices,” Wells says.

Connecting with the public is especially important now, given “the questioning of what science is telling us,” he says. “We’re trying to say it’s got real value in all of our lives.”

-