‘You have to have a new ride’

Pipeline of new hotel properties expected to make Virginia more competitive

‘You have to have a new ride’

Pipeline of new hotel properties expected to make Virginia more competitive

“It doesn’t feel like we’re in Norfolk anymore,” Dana Jo Decker remarked to friends while standing in line recently to check in at The Main, Virginia’s newest luxury hotel and conference center. “It feels like we’ve been transplanted somewhere else.”

While Norfolk’s downtown landscape was visible from the lobby’s glass atrium, a festive gala was underway inside during The Main’s soft opening in late March. Hotel staffers served champagne to guests waiting to collect room keys, while dancers — whose costumes evoked Norfolk’s mermaid sculptures — performed under giant helium-filled balls.

Visually, there was plenty to take in. A hot-pink ice cream sculpture stood near the elevators while a red, baby-grand piano added to the ambiance of Varia, the hotel’s Italian restaurant. Another stricking feature was a bookcase that opened into a private dining room.

“It was just a great vibe — happy, uplifting, energetic,” Decker, a local resident and member of a prominent business family, says of the $175 million, 22-story property.

Across Virginia, 46 new, expanded or renovated hotel properties are scheduled to open later this year and next year, representing an investment of $1.1 billion and more than 6,000 guest rooms.

According to HotelMarketData, which tracks projects in the planning and construction stages, the full pipeline of projects now in the works in the Old Dominion includes a projected 171 properties, with up to 25,000 rooms and a potential development investment ranging from $2.4 billion to $3 billion.

That’s a pretty healthy indicator, says Eric Terry, of the improved fortunes of Virginia’s hotel industry. It struggled after the Great Recession and the 10-year lows in occupancy and “RevPAR” (revenue per available room) seen during 2010. “I’m really encouraged by the amount of new investment that we’re seeing in the state,” says Terry, president of the Virginia, Restaurant, Lodging & Travel Association.

Driving the growth is Virginia’s thriving tourism and meeting industry, which drew more than 41 million domestic visitors to the commonwealth in 2015.

Those travelers spent $63 million a day, with total tourism industry revenue reaching $23 billion in 2015, a 2.3 percent increase over 2014. A portion of that business comes from the meeting and convention sector, which can pull in a weekend crowd of more than 1,000. (Tourism figures for 2016 will not be available until later this spring.)

Rita McClenny, president and CEO of the Virginia Tourism Corp. (VTC), the state’s promotional arm for the industry, says she is “thrilled” by the new development. “If we want to compete with other states, and we want more people to come to Virginia, one way to grow tourism is to have new product.”

New properties also offer amenities that today’s travelers are looking for: cutting-edge technology, keyless entry systems and high-end beverage and restaurant service that immerses visitors in the local culture. In other words, they give Virginia the modern “vibe” that Decker liked at The Main. One of its amenities is Grain, a fifth-floor beer garden and restaurant that serves 100 craft beers in a space that offers live music, a photo booth and two outdoor terraces, one with waterfront views of the Elizabeth River.

Geographic diversity

McClenny notes that new development is occurring not only in urban centers, but also in areas of Virginia that are turning to tourism as a way to diversify struggling local economies.

For instance, in far Southwest Virginia where coal used to be king, the Western Front Hotel in St. Paul is scheduled to open in September. The $7.2 million, 30-room boutique hotel will have a restaurant, Milton’s, run by Travis Milton, an award-winning chef known for preserving the culinary traditions of his native Appalachia. Other amenities include rooftop dining and a banquet and music hall. The hotel is close to Spearhead Trails, which offer more than 100 miles of trails for ATV enthusiasts. The hotel is expected to create 25 jobs in its first year.

The project’s developers are Williamsburg-based Cornerstone Hospitality and Roanoke-based Creative Boutique Hotels. The partners specialize in revitalizing historic buildings, transforming them into boutique hotels. Cornerstone Hospitality has several other hotels in the works: The Virginian Hotel in Lynchburg, a 115-room property scheduled to open by the end of the year; Hotel Weyanoke, a 70-room property in Farmville that plans to open in April 2018; and the Sessions Hotel in Bristol, a 70-room hotel opening in late 2018. The Sessions Hotel is located next door to the Birthplace of Country Music Museum and also will have a Travis Milton restaurant called Shovel and Pick.

Kimberly Christner, president and CEO of Cornerstone Hospitality, says boutique hotels represent one of the fastest-growing segments of the hospitality industry. “The neat thing about each of these properties is that they are all very different. This creates an opportunity for a traveler to go to different destinations in Virginia and experience the community that they’re in.”

Tourism gap financing

The Hotel Weyanoke in Farmville is one of five hotel projects that have taken advantage of the state’s Tourism Development Financing Program begun in 2011. The capital cost is $12.2 million, and the developers applied for 22.5 percent of that cost, or $2.7 million, in gap financing. The hotel is expected to create 76 full-time jobs.

Gap financing money isn’t taken from the state’s general fund. “All the money the state contributes is from the new taxes from the new revenue that the project creates,” says Wirt Confroy, director of business development for VTC. “It’s up to the developer to make the business a success. If for any reason, it ceases generating revenue, the locality and the state are not liable for anything. It’s a performance-based tax rebate, really.”

The program is designed to compensate for a shortfall in project funding that can’t exceed 30 percent of a project costing under $100 million or 20 percent of a project greater than $100 million. To get financing, a developer must partner with a locality. “The locality has to decide, ‘Do we have a deficit in the tourism business? Do we need lodging, dining or something new?’” says Confroy.

The program supports larger-scale tourism development projects that create jobs, tax revenue and visitor spending. VTC will assist a locality in creating an application for the financing, which must be submitted to and verified by the state comptroller. Applicants pay a $500 application and processing fee. If an application is approved, the project doesn’t get money until it opens for business and generates revenue.

At that point, the developer, locality and the state begin paying an amount equal to 1 or 1.5 percent (for projects over $100 million) of the project’s quarterly revenue to the lender until the gap’s debt service is complete. So, if a project’s quarterly revenue was $1 million, for example, the three parties would each pay 1 percent, or $10,000, for a debt payment of $30,000.

Developers still must get financing, and they still own all the debt, explains Confroy. State gap financing, however, reduces the amount developers would need from lenders.

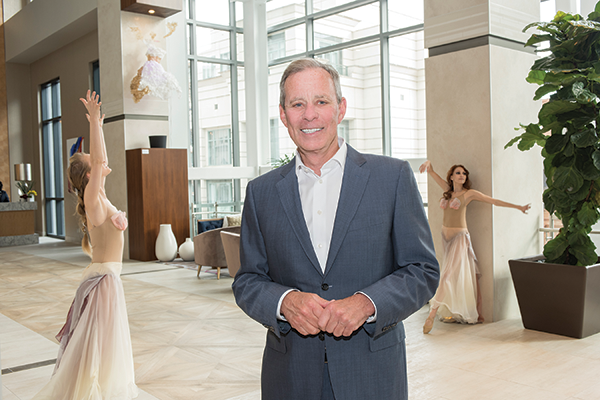

Bruce Thompson and his partners got gap financing on two projects: The Main in Norfolk and the ongoing renovation of the historic Cavalier Hotel in Virginia Beach. According to Confroy, the Norfolk project was approved for 9 percent in gap financing on $77.5 million for the hotel portion only. The city of Norfolk also kicked in nearly $87 million for the conference center and parking garage for the project, with the developer responsible for coming up with the rest of the $175 million total. The Main is expected to create 250 full-time jobs.

On the Cavalier, the state approved 12.4 percent in gap financing, or $18 million, for what was expected to be a capital cost of $145 million (for the Cavalier renovation and a new 300-room hotel on the oceanfront). However, Virginia Beach plans to update its application, Confroy says, since the City Council recently voted to let the Cavalier’s development group borrow an additional $6.5 million to build a third hotel at the resort complex.

Originally Cavalier Associates LLC planed to invest more than $300 million in the project, including more than $90 million in private investment, to renovate the Cavalier, build a Marriott Hotel across Atlantic Avenue on the oceanfront and add town homes, condos and a beach club. Plans to include a timeshare property were scrapped, with the developers opting to build an Embassy Suites Hotel to add more rooms and conference space to the oceanfront market. The Cavalier and Marriott projects are projected to create 385 full-time jobs.

Thompson says that, if it weren’t for public/private programs, major projects like The Main and the Cavalier “would never have been built.” During a recent hospitality roundtable sponsored by Virginia Business, Thompson acknowledged that he had a hand in shaping the gap financing legislation while serving in 2010 as chairman of a tourism subcommittee under then-Gov. Bob McDonnell’s Commission on Economic Development and Job Creation. Now the program “sits in the toolbox ready to go to provide the differential between market-rate deals and the aspiration of where a community wants to be to fill a void or gap in the market.”

Doing a gap-financing project, though, isn’t easy. “You have to have a lot of patience and some thick skin to get through the process,” says Thompson. “You know when you get involved that it’s going to be highly contested politically and the second piece … while there’s a lot of economic incentives that come along with public/private partnerships — it’s expensive to do from a documentation and legal standpoint, and it’s lengthy.”

Case in point: The rerouting of Atlantic Avenue to accommodate the renovation and expansion of the Cavalier resort complex has taken more than a year. In addition, Thompson says, he has been castigated in the local media on a regular basis, with members of the public questioning whether he has received preferential treatment over other developers and challenging whether public/private partnerships are appropriate for hotel projects.

New brands

Virginia Beach also welcomed its first Hyatt House hotel last month. The 19-story, 156-room oceanfront hotel cost nearly $80 million.

Another new brand is The Graduate Hotel. It opened in Charlottesville about a year ago, and AJ Capital Partners plans to open another of its college-themed hotels near Virginia Commonwealth University in Richmond this spring.

The hotel industry is segmenting products to broaden its appeal, and the fact that it wants to put new design concepts in Virginia helps give the state an edgier feel, says McClenny.

In another effort to make Virginia tourism-friendly, the VTC has launched a campaign to be more inclusive. “We are expanding our outreach to include LGBT travelers,” says McClenny.

Under Gov. Terry McAuliffe, the state created an LGBT (Lesbian Gay Bisexual and Transgender) Tourism Taskforce in 2014. Out of that initiative came new information that’s posted to the VTC website about how Virginia tourism businesses, communities and attractions can maximize their tourism potential with LGBT visitors, a group with high discretionary income that tends to spend more and stay longer than other visitors, according to the VTC.

Robert G. Roman, a Norfolk businessman who served on the taskforce, says he’s pleased with the efforts. “When people go on vacations, they want to be welcomed. And in certain parts of the state, it would be difficult to go and have a good experience. When the governor of the state says Virginia is open for business, it’s open to the LGBT community, we want them to come and we want them to come to our hotels and our cities … It sends a message of inclusivity.”

Travel officials only need to look to neighbor North Carolina for a cautionary tale. In late March, the Tar Heel state repealed its year-old “bathroom bill,” which required transgender people to use public restrooms that corresponded to the sex listed on their birth certificates.

Backlash from the legislation cost the state economy millions and, over a dozen years, could have cost as much as $3.76 billion, according to an analysis by The Associated Press. Some major companies, including PayPal and Deutsche Bank, canceled plans to expand in North Carolina. In addition, the NBA moved its All-Star Game from Charlotte, and the Atlantic Coast Conference and NCAA canceled plans to hold football and basketball championship games in the state. Since the repeal, the NCAA has said it would reconsider North Carolina as a host for future championship events.

Travel bans create uncertainty

International travelers have been on edge this year after President Donald Trump issued two executive orders prohibiting travelers from several Muslim-majority countries from entering the U.S. The orders have been blocked by federal courts.

Trump says the travel bans are intended to protect national security. While the U.S. Travel Association supports efforts to improve security, it has urged Trump’s administration to welcome legitimate travel. “Mr. President, please tell the world that while we’re closed to terror, we’re open for business,” Roger Dow, CEO and president of the country’s largest travel organization, said in a recent statement.

Drawing international visitors through Washington Dulles International Airport in Northern Virginia has typically been a benefit for Virginia, because frequently visitors coming to see the nation’s capital take side trips to Virginia. So far, Trump’s travel bans don’t seem to be having a negative impact, with international traffic up 12 percent in January at Dulles International.

Yet travel bans contribute to an environment of uncertainty, which isn’t good for travel. “Our industry is doing everything we can to get the administration’s attention on that,” says Jonathan Grella, executive vice president of public affairs for the U.S. Travel Association. “We hope that the president’s hotelier industry instincts kick in, and they issue a statement of some type of reassurance. If international travel dips, we’ll end up with two problems: the security problem and an economic problem.”

-