What if Hillary was Trump’s vice president?

A new book by Bob Woodward and an anonymous op-ed piece in the New York Times paint a disturbing picture of the Trump White House.

They describe senior officials striving to restrain Trump’s impulsive actions.

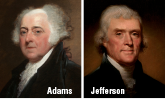

Some have called this White House power struggle “unprecedented,” but it is not. The president and vice president once were the leaders of opposing parties. Imagine the trouble Trump would have if Hillary Clinton was his vice president? That was what essentially happened after the 1796 election.

The pairing of two people from opposing parties in the same administration didn’t seem so odd at the time. But the groups that Adams and Jefferson represented would become locked in a death struggle in the next election.

In “Friends Divided,” Pulitzer Prize-winning historian Gordon Wood recounts the long, complicated relationship between the two men.

Jefferson and Adams met in the Continental Congress and were assigned to the committee preparing the Declaration of Independence. Adams insisted that Jefferson compose the document because the Virginian was the better writer.

They became close friends while serving as envoys in France during the Revolutionary War. Both returned to the U.S. to serve in Washington’s first administration.

That’s when their ideas began to collide. Adams and Jefferson were united in their quest for independence, but their political philosophies were very different.

Despite being a Southern aristocrat, Wood writes, Jefferson had absolute faith in democracy and the collective wisdom of the public. He favored a government with limited powers.

Adams, on the other hand, feared rich oligarchs would take control of the U.S. government. Therefore, he supported a strong presidency with powers similar to a king’s. Adams in fact proposed addressing the president as “His Highness.” Luckily, Washington insisted on “Mr. President.”

During Washington’s tenure, the battle lines between Federalists and Republicans were drawn. Jefferson repeatedly clashed with Alexander Hamilton, a Federalist leader who was treasury secretary, about expanding the powers of the federal government.

The Federalists didn’t see themselves as members of a political party: They were simply “the government.” Their opponents were “Jacobins,” supposed agents of the French revolutionaries.

France, in fact, became a flashpoint in a growing rift between Adams and Jefferson. As president, Adams worried constantly about war with France, which was in the throes of violent revolution.

Jefferson, meanwhile, remained sympathetic to France, hoping it would become a republic similar to the U.S.

Political tensions rose to the point that the Federalists passed the Alien and Sedition Acts, legislation aimed at limiting U.S. citizenship and stopping attacks on the administration by Republican newspapers.

In reaction, Jefferson and James Madison secretly authored the Kentucky and Virginia Resolutions. Passed by the legislature of each state, the resolutions argued that the Alien and Sedition Acts were unconstitutional.

Convinced that a French attack was eminent, the Federalists enlarged the U.S. Army and effectively made Hamilton its commander. In his book, Wood describes Hamilton at this time as “a Napoleonic figure” whose grandiose plans included invading and breaking up Virginia.

The conflict between Republicans and Federalists finally came to a head in the 1800 election. Each side considered victory by its opponent as a death knell for the young nation. The campaigns waged by both parties are considered among the most vicious in U.S. history.

Hamilton helped seal Adams’ defeat by scheming to throw the election to the president’s Federalist running mate, Thomas Pinckney. Hamilton also wrote a scathing, 54-page critique of Adams that fell into the Republicans’ hands.

Crushed by his defeat, Adams refused to attend Jefferson’s inauguration and retreated to his New England farm.

His fellow Federalists consoled themselves with the notion they would be back in power in four years. Instead, the party never elected another president.

Luckily, the nation did not fall into ruin under Jefferson’s leadership. Despite his preference for limited government, he negotiated the Louisiana Purchase without knowing for certain if the deal was constitutional.

Adams and Jefferson never saw each other again. Nonetheless, at the urging of a mutual friend, they began corresponding in 1812. During the next 14 years, they exchanged 158 letters.

“You and I, ought not to die, before We have explained ourselves to each other,” Adams said in one letter.

He died on July 4, 1826 — the 50th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence. Adams’ last words were, “Thomas Jefferson survives.” But he was wrong. Jefferson had passed away earlier the same day.

e