Waiting for the ax to fall

Government contractors throughout Virginia are facing the consequences of automatic federal budget cuts scheduled to take effect on Friday.

The cutbacks,known as sequestration, could push the commonwealth into a recession costing more than 200,000 jobs.

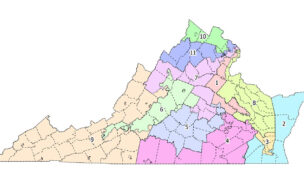

Virginia is especially vulnerable to the effects to sequestration because federal spending represents about a third of the state economy. Last year, the federal government awarded $54.6 billion in contracts in the Old Dominion, according to Bloomberg Government.

“All in all, this is the dark ages of federal contracting,” says Gary Lisota, president and CEO of Valkyrie Enterprises in Virginia Beach. “It’s a nervous time.”

Sequestration is part of an effort to reduce government spending by $1.2 trillion during the next 10 years. Originally, $85 billion in cuts were scheduled to take effect this fiscal year. The Congressional Budget Office, however, says $44 billion in cuts will take effect now, with the remaining $41 billion being spread over coming years.

Half of the automatic cuts will come from defense spending, which make up about 70 percent of Virginia’s federal contracts.

In addition, the Defense Department is expected to furlough 90,000 civilian employees in Virginia beginning the last week of April. The employees would be forced to take one day of leave a week without pay for 22 weeks, reducing their gross pay by $648.4 million.

Also, Army base operation funding would be cut by about $146 million in Virginia, and the Navy would cancel the maintenance of 11 ships based in Norfolk, a move that could cause shipyard layoffs in Hampton Roads..

Two economists — Stephen Fuller, director of the Center for Regional Analysis at George Mason University, and Christine Chmura, president and chief economist of Chmura Economics and Analytics in Richmond — last summer collaborated on a study predicting sequestration will cost Virginia 207,571 jobs.

“Some of the cuts have already occurred,“ Chmura says. “State employment is growing at a slower rate than the national [average]. And professional business services employment growth — a sector that has greatly benefited in the past from federal spending — has slowed considerably.”

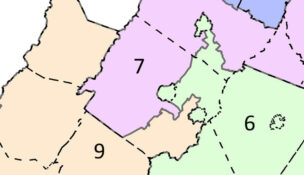

While she does not expect sequestration to cause a national recession, Virginia’s economy would retreat, with Northern Virginia and Hampton Roads being the hardest hit. Without sequestration, total employment in those regions was expected to rise 1.4 percent and 0.8 percent, respectively. However, the effects of automatic cuts could be short-lived. “We expect a deal will be worked out,” Chmura says.

Analysts say major defense contractors such as Fairfax County-based General Dynamics and Northrop Grumman, Virginia’s largest Fortune 500 companies, will not be affected immediately by sequestration because they have contracts that cover several years.

The story, however, is different for small contractors supplying a specific product or service, many of whom already have seen a slowdown in government business.

Valkyrie, an engineering and technical services firm primarily serving the U.S. Navy, last year was recognized as the fastest-growing company in Virginia, with revenue rising 4,732 percent from 2007 to 2010. Lisota had expected revenue to leap another 67 percent this year.

Now, however, “it’s really hard to see that we can achieve that level of growth,” he says. “If I had 25 percent growth this year, I would consider that to be a victory.”

Lisota says all new project starts have been delayed, in many cases indefinitely, because his government customers still don’t know how much money they will have to spend.

“For us, in this case, we have no weather vane at all …it’s scary,” says Lisota, who employs 202 workers “We’re holding back on investment in people, hardware, software, all kinds of things. It is difficult to predict what the impact is going to be in terms of the current work we have as well as growth.”

John Braun, president and chairman of Dynamis Inc. in Arlington, says a contract that his company expected to be renewed for 12 month instead was renewed for only two.

The company provides advice, analysis, IT solutions, training and analytical support to senior government leaders, principally in defense and homeland security.

It now has 50 employees after recently laying off two. Braun describes the current business environment as chaotic.

“The most important thing to be successful in business is to know your environment, and a business can’t survive in periods of instability because you need stability to be able…to keep your company going,” he says.

Jeffrey D. Wassmer, president and CEO of Spectrum in Newport News, still is waiting to hear how sequestration will affect his consulting company, which employs 360 people. But the uncertainty surrounding the budget cuts already has cost him several good engineers who have left the company to work in other industries.

Wassmer says sequestration has become a political football in a contest between Republicans and Democrats.

“Campaigning is one thing, but execution and government is another thing,” he says. “These guys have to find ways to compromise. Look at our statehouse. We passed a transportation bill by not everybody getting what they wanted. That same attitude has to exist in Washington.”

The Wall Street Journal reported Thursday that the White House and Republican congressional leaders were willing to let the March 1 deadline pass without action because they believed the start of budget cuts would strengthen their respective bargaining positions.

Ironically, no one thought the sequestration process would get this far. The cuts were designed to be draconian so that Congress would be forced into a bargain on federal spending. That deal never took place.

The Budget Control Act of 2011, approved by Congress to end a battle over the debt ceiling, set up a bipartisan committee of 12 lawmakers who were to find an additional $1.2 trillion in savings in the budget.

The automatic cuts were to take effect this year only if the committee failed to come up with an agreement. Those talks collapsed with no resolution. Sequestration was supposed to start in January but was postponed until March 1 by a last-minute agreement on tax cuts and tax hikes enacted to avoid the “fiscal cliff.”