The road ahead

Officials are deciding how to spend new transportation funds.

The road ahead

Officials are deciding how to spend new transportation funds.

In the early 1990s, members of the Hampton Roads Chamber of Commerce started to see the need for additional transportation money in the region.

Congestion was only getting worse in the region’s network of roadways, bridges and tunnels, and the Virginia legislature had last put significant new money into the commonwealth’s transportation system in 1986.

“The only thing that we had seen was declining sources of revenues and increased needs and increased congestion,” says Jack Hornbeck, the president and CEO of the Chamber, who is retiring in September after 26 years at the organization.

The chamber had no idea how long it would have to wait. After 27 years of partisan bickering, failed regional referendums and a 2007 regional taxing plan that was ultimately struck down by the Supreme Court of Virginia, the General Assembly delivered the first significant boost of ongoing statewide and regional revenues for transportation.

Through a series of contentious new taxes and fees that start July 1, Virginia’s statewide transportation system will see an estimated $4 billion in additional revenues during the next six years, or about $880 million a year by 2018. Through regional components, the plan will also raise an additional $1.9 billion for Northern Virginia and $1.3 billion for Hampton Roads during the next six years.

“This bill is a game changer for Virginia,” says Transportation Secretary Sean Connaughton. “Not only does it put our transportation program on a stronger foundation, but it also provides enough revenues to expand roads, rail, transit, air, airport and seaport projects. This legislation will mean more investment and more jobs for Virginia.”

Yet years of inaction have taken their toll on Virginia’s transportation system, and the cost of projects has gone up. And so while the new monies will pump new life into Virginia’s transportation system, its effectiveness will rely on how wisely the money is spent.

“If we choose wisely, then we can really get some significant traction and really make some progress over the next 10 years on fixing transportation,” says Bob Chase, president of the Northern Virginia Transportation Alliance, a group of business leaders that has advocated for more transportation funding. “At the same time, there are so many projects on the ‘wants’ list as opposed to the ‘needs’ list that, if we don’t choose wisely, we could spend money on things that don’t have a great return on investment.”

An aging network

A lack of new transportation funds has left Virginia’s transportation infrastructure with a long list of high-priced needs. The 17.5-cents-per-gallon gasoline tax, the state’s largest revenue source for transportation, today is only worth 45 percent of its 1986 value. Since 2002, $3 billion has been diverted from Virginia’s construction funds to keep up with maintenance of the roads. And no funds have been available in the construction formula since 2009. (Any construction over recent years has been funded with matching money from federal grants, public-private partnerships and bonds that were part of previous transportation packages.)

The plan that starts July 1 makes Virginia the first state to eliminate its gasoline tax, which has become an unreliable source of transportation revenue as cars become more fuel-efficient. Instead, Virginia’s new plan includes a percentage-based tax on wholesale gasoline and diesel, allowing the revenue to rise with inflation and gasoline prices.

The plan also raises revenues through a $64 registration fee on hybrid and alternative vehicles, an increase in the statewide sales tax and an increased share of general fund revenues. (See chart on this page for more details.) Virginia also would dedicate a share of sales tax collected ($380 million over six years) if Congress passes the Marketplace Equity Act. It would allow states to collect sales tax from online retailers. If that bill does not pass by Jan. 1, 2015, the wholesale tax would increase further.

Northern Virginia residents will see additional sales, hotel and home sales taxes, while Hampton Roads will have additional sales and wholesale gasoline taxes to fund their own plans.

The state plan certainly has its critics. Among the complaints:

- Elimination of the gas tax separates the funding of transportation from the users of the transportation system;

- The poor will be disproportionally affected by the new taxes;

- The plan adds a registration fee for alternative-fuel vehicles;

- It doesn’t produce enough revenue to cover all of Virginia’s transportation woes;

- And, of course, it faced huge criticism for raising taxes.

Yet, controversy surrounding the bill reveals why it took almost three decades for the General Assembly to pass a transportation funding overhaul. In the end, even supporters admitted they weren’t pleased with all aspects of the bill.

“It was a pleasant surprise that it came out the way it did,” says Chase, giving specific praise to McDonnell, Speaker of the House Bill Howell, Senate Republicans and House Democrats. “It clearly was an example of people being willing to give up a little to get a lot.”

So, what now?

So, with so many needs, how will this money be spent?

The Commonwealth Transportation Board (CTB) is currently holding public hearings on its plumped up six-year improvement plan, which will be finalized in June.

Connaughton says that he expects statewide revenues to fund or spur more than $5 billion in capital projects during the next six years, as well as support a fully funded maintenance program. In addition to a variety of new construction projects, the new funds will speed up some public-private partnership projects and add money to mass-transit priorities. “We believe it’s essential that the public see as many projects moving forward as quickly as possible,” he says. “The public needs to see the benefits of the additional money they are spending.”

The first $500 million of construction money each year must be divvied up according to a temporary funding formula passed by the General Assembly last year. The formula dictates that spending will follow these guidelines: 25 percent to bridge repairs, 25 percent toward advancing high-priority statewide projects, 25 percent to pavement reconstruction, 15 percent to public-private partnerships, 5 percent to paving unpaved roads and 5 percent to smart roadway technology.

When revenues provide for more than $500 million in construction money, starting in fiscal year 2017, the money will be divided according to the 1986 formula, which is divided among primary, secondary and urban roadways. “The money wasn’t enough to get projects done,” under the old formula, says Connaughton. “What the temporary formula allows us to do is focus on things that we could move forward very quickly on real projects.”

Some of the projects included in the draft six-year plan are: extension of passenger rail to Roanoke, increased train service between Richmond and Norfolk, Interstates 95/64 overlap improvements in Richmond, I-66/Route 28 interchange improvements, I-95/Route 17 improvements over the Rappahannock River, I-64 widening between Williamsburg and Newport News, Route 29/Route 666 interchange improvements in Culpeper and the Dulles Metrorail project.

Drivers should expect to see major paving operations begin soon to improve Virginia’s roadways, making for a smoother ride and less wear and tear on vehicles, says Connaughton. “You will see historic levels of effort on pavement,” he says. The state expects to spend $450 million annually on pavement operations during the next few years — double what it normally spends. “We believe the primary and secondary systems will be at their highest level of pavement condition in our history.”

Regional authorities

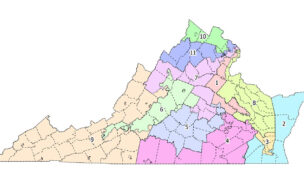

The transportation plan provides for additional relief for Virginia’s most congested hotspots: Northern Virginia and Hampton Roads.

The additional taxes and fees are expected to bring in more than $300 million a year for the Northern Virginia Transportation Authority and more than $200 million a year for the Hampton Roads Transportation Planning Organization. The new plan has created a good, but complicated, issue for these organizations: figuring out how to best spend the new money.

“It won’t fund everything we need,” says Dwight Farmer, executive director of the Hampton Roads Transportation Planning Organization. “When I add up all of the mega-projects [needed in Hampton Roads], the cost estimates for the next 20 years range from $19 billion to $23 billion.” He plans to present a plan to the HRTPO board for the organization to divide its money among mega-projects in the area, regional interstate projects and local projects. “The $200 million [a year] is a great addition to our revenue stream, but it doesn’t really fund those mega-projects that are multiple billions of dollars.” Any mega-project, he says, certainly will need another revenue component, tolls.

The organization will be aided by its list of 155 candidate projects that each contain cost estimates and prioritization score rankings.

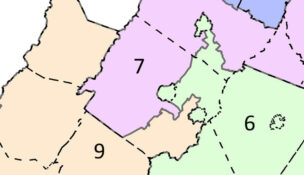

The Northern Virginia Transportation Authority has set up working groups to perform the same arduous analysis of the region’s proposed projects. Thirty percent of the money collected in the region through additional taxes on retail sales, hotel stays and home sales must stay in each locality to be used for transportation projects that improve congestion.

The rest of the money goes to the authority, which is currently identifying shovel-ready, cost-effective projects that will provide the most relief for the region.

“The lack of infrastructure investment has really created a crisis,” says Martin Nohe, chairman of the authority. “What we’re focused on at the Northern Virginia Transportation Authority is getting projects on the ground that improve people’s commutes as soon as possible.”

Both authorities are hoping to leverage their money by pooling funds with state resources to focus on specific projects, such as moving projects in the Virginia Department of Transportation’s six-year plan up a couple of years.

Now that the state has added new transportation money, the Northern Virginia Transportation Alliance ’s new role is trying to make sure money is spent on projects that will benefit the region rather than individual localities. “The business community understands that there’s not a Fairfax economy and a Loudoun economy,” says Chase, the head of the alliance.

“You’re talking more than $3 billion [in regional money over 10 years],” he says. “Which, if you leverage that and combine that with state money and federal money, you have the ability to really make a difference in terms of not only improving your transportation network, but providing the capability to sustain longer-term economic investment and global competitiveness.”

New taxes and fees in the transportation bill

- Eliminates the 17.5 cents-per-gallon gasoline tax.

- Adds 3.5 percent wholesale sales tax for gasoline, 6 percent on diesel.

- $64 annual registration fee for hybrid vehicles, alternative fuel vehicles and electric motor vehicles.

- Raises statewide sales and use tax from 5 percent to 5.3 percent.

- Motor fuel tax on gasoline will increase from 3.5 percent to 5.1 percent Jan. 1, 2015, unless the federal government passes the Marketplace Equity Act, allowing Virginia to collect sales tax on Internet sales.

- Increases share of existing sales tax dedicated to transportation from 0.5 percent to 0.675 percent, phased in over four years.

Funding highlights over five years

- Grows construction program by $2.4 billion

- Generates $1.8 billion in additional funding for maintenance

- Increases funding for Virginia’s transit providers by $509 million

- Provides $256 million for intercity passenger rail

- $300 million to support Dulles Rail project

Regional taxes

The law applies additional state taxes and fees in planning districts meeting certain population, motor vehicle registration and transit ridership criteria.

Northern Virginia:

- New taxes: 2 percent transient occupancy tax, 15 cents per $100 of assessed value on home sales, additional retail sales tax of 0.7 percent (bringing total in the region to 6 percent)

- Designation: 30 percent of money collected stays in locality where it is collected for local congestion mitigation projects. Remainder goes to Northern Virginia Transportation Authority to use on regional projects.

Hampton Roads:

- New taxes: Additional sales tax of 0.7 percent, 2.1 percent tax on wholesale distributors of motor fuels.

- Designation: Revenues generated are to be used on new construction of roads, bridges and tunnels as approved by the Hampton Roads Transportation Planning Organization.

o