The play is under review

Scrutiny of economic incentives is growing throughout the country

Robert Burke //February 28, 2017//

The play is under review

Scrutiny of economic incentives is growing throughout the country

Robert Burke //February 28, 2017//

It’s been a tough time lately for the Virginia Economic Development Partnership. First came a bad review last fall by the state’s watchdog agency, the Joint Legislative Audit and Review Commission (JLARC). “VEDP is not an efficient or effectively managed organization” says the first sentence in the JLARC summary.

That public spanking was followed by a legislative turf battle between Gov. Terry McAuliffe and General Assembly Republicans, with each arguing their side should have more power over the commonwealth’s top economic development organization.

In the midst of all this, VEDP employees were getting used to a new boss — Stephen Moret, an economic development executive from Louisiana, who became CEO on Jan. 1 (see interview).

It may be, however, that the most important change the VEDP needed is already in effect. Legislation approved in last year’s General Assembly session created a JLARC unit to evaluate — in a more diligent way than had been done so far — whether VEDP incentives and strategies actually work.

Experts in the field of state-level economic incentives say that type of change is a big deal. “Virginia actually took a really important step last year by creating a new unit within JLARC to regularly study the results” of its incentive program, says Melissa Maynard, who studies economic development tax incentives for The Pew Charitable Trusts’ state fiscal health and economic growth project. “Every state uses incentives, but lawmakers have often lacked good information about how incentives are working,” she says.

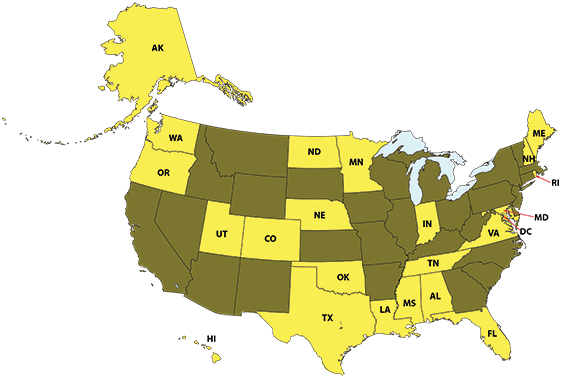

22 states and D.C.

The Virginia legislation requires regular review and evaluation of all major incentives, including grants and tax preferences. That includes measuring the economic benefits to Virginia of the total spending on economic development initiatives at least every other year.

The Virginia legislation requires regular review and evaluation of all major incentives, including grants and tax preferences. That includes measuring the economic benefits to Virginia of the total spending on economic development initiatives at least every other year.

While it would seem obvious that states want to know how their incentives are working, many apparently don’t have a strategy for finding out. According to Philadelphia-based Pew, 22 states and the District of Columbia have enacted similar incentive evaluation programs in the past five years. Last year alone, six states — including Virginia — created review projects.

Research and advice from Pew are two of the reasons more states are taking this step. People such as Maynard work with state lawmakers, agencies like VEDP and economic development officials to develop programs that fit a particular state’s needs.

A Pew study shows how common it is for states to mismanage the money spent on economic development efforts. Every state has some kind of incentive program in place, and most have several. Nonetheless, many states don’t have a dependable way to measure incentives’ effectiveness.

Inaccurate estimates

In other cases, states that implemented high-quality evaluations are finding out how wrong their previous estimates have been. In Minnesota, for example, state officials estimated that each job created in its Job Opportunity Building Zones cost about $5,000, according to Pew research. But Minnesota’s legislative auditor found each job actually cost the state five or six times more.

In the past, the absence of more rigorous evaluations of incentives allowed state leaders to claim that all was well, Pew reports say. Just before the recent recession hit, for example, Pennsylvania’s economic development program said the state’s Keystone Opportunity Zone program had created nearly 64,000 jobs during an eight-year span. A year later, it lowered that estimate to fewer than 35,000 jobs, and the next year a legislative review declared that neither figure was reliable.

What makes states lose track of the effectiveness of incentives? “One of the challenges is a lot of the spending is through the tax code,” Maynard says. Those incentives don’t go through the budget process, so they often don’t get the scrutiny that budget spending does.

JLARC ‘well-equipped’

Of course, such evaluations don’t always find failure. Sometimes states discover an incentive program is working but learn ways to make it even better. Maynard says that, a few years ago, Minnesota’s angel-investor tax credit was set to expire, and lawmakers were trying to decide whether to extend it. An evaluation found the incentive was cost effective. As a result, legislators not only extended it; they expanded funding from $12 million to $15 million.

Rigorous evaluations turn up details that matter. Ohio took a close look at some of its incentive programs that required matching funds from local governments for companies to be eligible for grants. But an evaluation showed that the local match requirement also forced companies to accept subsidies they didn’t want in order to qualify for the incentive program they did want. And, the money spent by businesses on lawyers and accountants to process those unwanted incentive programs was more than the benefit. So Ohio dropped the local match requirement.

“The high-quality evaluation that we like to think of is way beyond ‘yes’ or ‘no’ verdicts,” Maynard says. “So, even when an incentive is working well, evaluations can point out ways that they can be even more effective.”

35 recommendations

Pew researchers also say another advantage of setting up a regular schedule of evaluations is that the process lets businesses know when an incentive they might want to use is going to be reviewed. Businesses generally don’t like surprises.

Among the 35 recommendations in its VEDP review, JLARC does have something to say about incentives. The report recommends, for example, a more consistent approach in evaluating projects that might be considered for incentives. JLARC also calls for regular audits of the job creation and wage claims of companies receiving incentive grants. That kind of effort would require some data from the Virginia Employment Commission and the state’s Department of Taxation.

The watchdog agency also calls on VEDP to create a separate division that would be responsible for administering incentives. It wants at least three people in this division to “have the qualifications and training necessary to perform the work assigned to them,” according to the JLARC recommendations.

(Legislation passed by the General Assembly in Februrary will create a VEDP division to oversee financial incentives. It also will reduce the partnership's board from 24 to 17 members.)

Compared with other states, Virginia is seen as a “light” incentive state, awarding $384 million in state grants over the past decade. Yet prior to January 2016, JLARC reported that the awards were made without a formal, written due-diligence process, a situation that exposed the state to possible fraud and financial loss.

Political distractions

JLARC’s report wasn’t just about VEDP’s mission and how to accomplish it, but also about how it works, or doesn’t work.

Clemente was named to the board by then-Gov. Bob McDonnell in 2014 and became its chairman last year. “I think VEDP has done fabulously well, considering the circumstances,” he says. He rejects criticisms that focus on specific failures of VEDP efforts with some companies. “If you’re running a bank and you don’t have bad loans, then you’re not working hard enough,” he says.

He thinks the current amount of involvement VEDP has with any governor’s cabinet is a distraction. In addition to Northam, four current cabinet members and community college Chancellor Glenn DuBois are ex-officio board members. In his proposed legislation, McAuliffe wanted to make the secretary of commerce and trade the permanent chairman of the VEDP. “You’ve got the entire cabinet sitting on your board, and every time the governor goes overseas, you’ve got to stop to help the governor,” Clemente says.

Plus, Clemente says, the partisan split that regularly occurs in Richmond doesn’t help VEDP. “You should not be in a position where one year you’ve got a champion, and the next year you don’t,” he says. “Who is your boss? The General Assembly says they’re the boss, and the governor says he’s the boss. The taxpayers are the real boss, and they don’t get a say at all.”

Clemente says the state should give VEDP a dedicated source of funding, and then focus on the outcomes.

“They could give us benchmarks. If we did not produce, then they could adjust the funding,” he says. “So it’s not like a blank check. That’s the way I’m going to present it in any further discussions. Give us the funding and give us the benchmarks instead of trying to run the place.”

VEDP gets 98 percent of its dollars from the state. This year that funding will be $27 million, not including money for incentive programs. (During this year’s session, the General Assembly was considering a move to put an additional $1.5 million in the current two-year budget — earmarked in part for marketing initiatives — into a reserve with contingencies that the money be released only if VEDP began implementing changes recommended in the JLARC report.)

“The way the VEDP works now is under the thumb of the governor,” Clemente says. “The VEDP staff has to draw up a proposed budget; they have to sell that idea to the governor; and … then he has to sell it to the legislature. I don’t know how you run a company when you have no idea what your revenue stream will be.”

Some states have a different approach.

In South Carolina, the Coordinating Council for Economic Development receives a dedicated stream of revenue, capped at $20 million a year, from utility taxes. And in Ohio, the operation of the state’s liquor stores provides funding for the state’s economic development efforts. In 2015 that revenue source tallied $90 million.

Clemente says the common desire of governors to claim credit for big job growth means that too much attention goes to urban areas like Northern Virginia and Hampton Roads. Those regions are going to get jobs anyway, he says.The places that really need the help of VEDP are the rural regions. “I think we have a moral responsibility at VEDP to figure out how to create jobs in those areas,” Clemente says. “If all we are is a booking service for the governor, so he can say he created 20,000 jobs, that’s not helping the state.”

Focus on site development

In that argument Clemente has an ally in Moret, VEDP’s new CEO. Getting a consistent funding stream is “the Holy Grail” for economic development efforts, Moret said in a late January interview.

And the state’s rural regions “need a much more robust, customized workforce training program. I think doing something not unlike what Louisiana and Georgia and Alabama have done would make a world of difference for rural Virginia.”

Virginia also needs a better supply of ready-to-go sites. “We need to place a bigger focus on site development,” Moret says. “I don’t want to seem like I’m harping on rural Virginia over and over, but I just really want to see us be successful across the commonwealth. And that’s a place where some other states have put a lot of investment, in developing sites and getting sites prepared.”

Moret and Clemente’s view suggests at least a different measure of what defines success. “Some folks think this is all about incentives,” Moret says. “Incentives have a place, but it’s just one piece of what a great state economic development organization does.” The ideal organization would be “professional, fast, creative and innovative.”

And, says Clemente, it will deliver results to those places that need help the most.

-