The new Midtown Tunnel

Promising relief for motorists, the $2.1 billion job is the state’s most extensive public-private project to date

Virginia Business //March 27, 2015//

The new Midtown Tunnel

Promising relief for motorists, the $2.1 billion job is the state’s most extensive public-private project to date

Virginia Business //March 27, 2015//

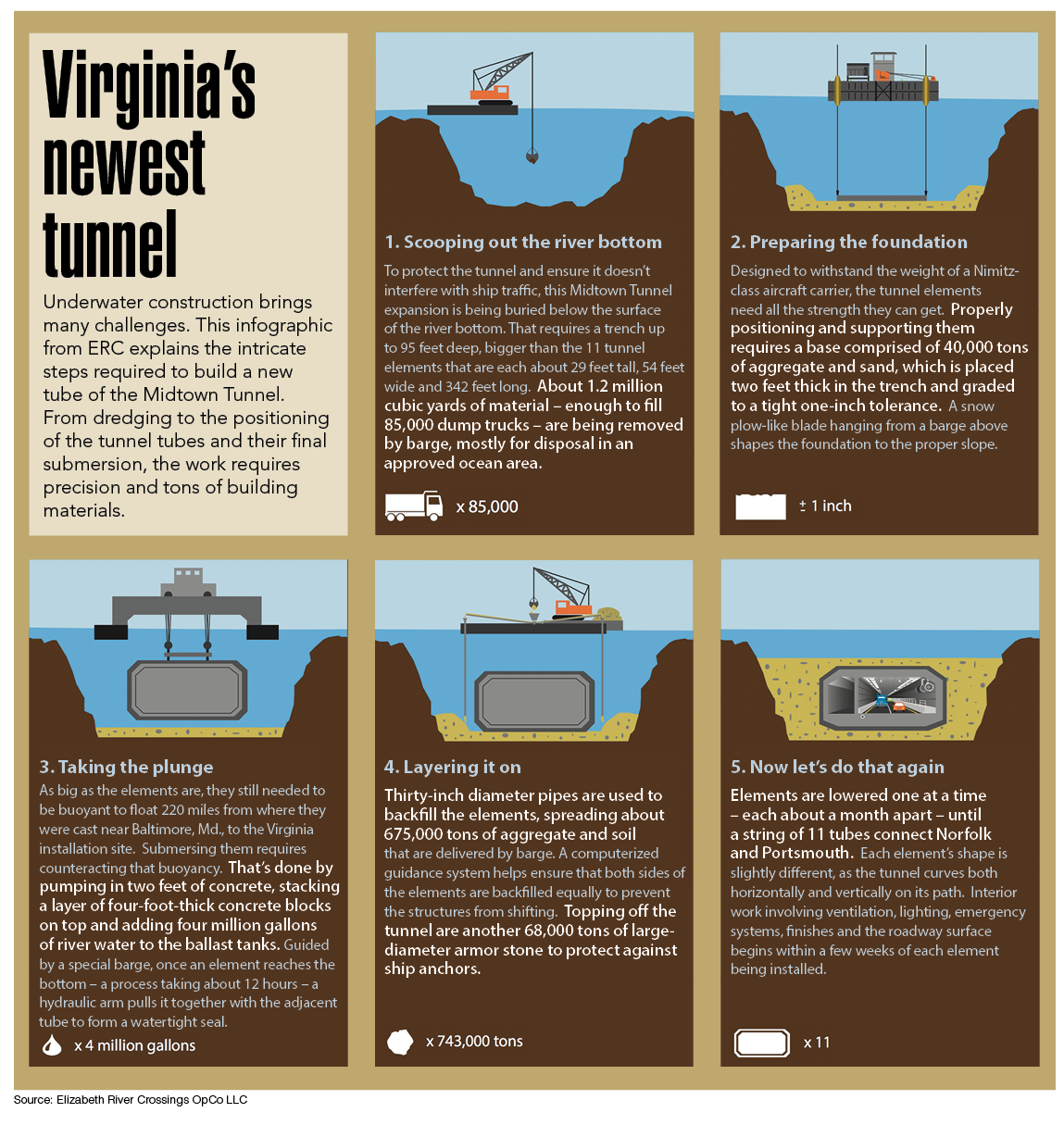

Precision is key when it comes to towing 16,000-ton concrete elements down the Chesapeake Bay before submerging them below the bottom of the Elizabeth River to create the new U.S. 58 Midtown Tunnel.

It will take 11 of these elements — each the size of a football field — to construct the centerpiece of the state’s most complex public-private transportation project to date. Still more than a year from completion, the long-awaited expansion of the tunnel — which links the cities of Portsmouth and Norfolk — already has won national acclaim because of the scope of its engineering challenges. Yet its biggest beneficiaries will probably be Hampton Roads’ motorists who have endured decades of hair-raising congestion on what is the most heavily traveled, two-lane road east of the Mississippi. During the work week, nearly 40,000 vehicles a day travel through the narrow, 23-foot tunnel.

A dry dock at Sparrow’s Point, Md., near Baltimore is the construction site for the reinforced concrete elements. The work is being done in Maryland, because no dry dock in Hampton Roads large enough to meet the construction schedule was available. That means each element, which measures 29-feet-tall by 54-feet-wide and 342-feet-long, must be individually floated 220 miles to its new underwater home. Then a special barge submerges each piece into a trench as deep as 95 feet below the river bottom — a delicate process that takes 12 hours. A hydraulic arm connects the element to an adjacent tube, forming a watertight seal. So far, six of the elements have been put in place. The final five are expected to be immersed by September. By October, construction workers should be able to walk from one end of the nearly mile-long tunnel to the other.

The Virginia Department of Transportation owns and oversees the project, while ERC operates and maintains the infrastructure until 2070. A joint venture between Skanska Infrastructure Development, a global construction firm with offices in Virginia, and the New York-based firm of Macquarie Group and Real Assets, ERC was formed to design, build, maintain and operate the 51 highway miles of infrastructure.

The new Midtown Tunnel is Virginia’s largest road building project in 20 years and represents one of the most extensive public-private partnerships in the nation. The new tunnel and connecting highway extension are expected to cost $1.47 billion, with operations and maintenance totaling $2.2 billion over the life of the project. Funding sources include $675 million in private activity bonds, a $463 million Federal Highway Administration loan, $272 million in private equity, and $169 million in project revenue during construction. The state also kicked in $391 million initially to reduce the cost of the tolls and later made another contribution of $113 million to defer the commencement of tolls, which began on Feb. 1, 2014. In January of that year, Virginia’s Commonwealth Transportation Board approved another $82.5 million over three years to further reduce the tolls amid much controversy about making motorists pay while the project was still under construction.

Some public officials expect the improved transportation network to unleash an economic bonanza in a region frequently passed over for corporate headquarters in part because of highway congestion. According to figures from ERC, the project is expected to generate a $170 million to $254 million annual increase in Hampton Roads’ gross regional product. The thinking goes that improved connectivity between cities would lead to greater military readiness and additional access for trucks traveling to and from the Port of Hampton Roads. Plus, officials expect a reduction by 30 minutes in daily commute times for motorists who can expect to save $66.3 million in annual fuel costs since the tunnel will be less congested.

So far, work on the tunnel is ahead of schedule. That’s good news for Greg Woodsmall, ERC’s chief executive officer, and Dallas Marlow, the project’s construction director. These men have labored over the details of construction, especially when it comes to submerging the new tunnel. “It’s a tremendous amount of engineering technology that requires tremendous job planning,” Marlow says. “You only have a one-inch tolerance between each element to get them in place. We can’t risk being wrong.”

Designed to withstand the weight of a Nimitz-class aircraft carrier, the new tunnel is only the second in the nation composed entirely of concrete, instead of a traditional steel-shell. The concrete makes the structure easier to seal and less likely to develop leaks. “We ran over 100 test batches of concrete for the tunnel tubes to ensure that they would meet the specifications and workability requirements,” Marlow says.

Built to last 120 years, the tunnel includes jet fans, a deluge system, fire sensors, motorist aid phones, video monitoring and a separate escape corridor.

At mid river, the bottom of the element reaches 95 feet below the surface of the river’s bottom, while the road deck is 90 feet below, and the top of the tube sits at 65 feet below the river’s bottom. This positioning protects the tunnel and prevents it from interfering with ship traffic.

In addition, the tunnel boasts a 10-foot-high drainage system. It’s designed to prevent flooding and protect one of the region’s major routes for hurricane evacuation. “We almost lost the Midtown Tunnel during Hurricane Sandy,” Marlow says. “The drainage system backs up at an elevation of 6½ feet. The water got up to seven feet. Water was rushing in, and we were frantically pumping it out. Luckily the river backed off at the last minute.”

Such enhancements are one reason Roads & Bridges magazine recently named the project the No. 1 Road Project in North America for 2014. The trade publication, which honors the top 10 projects for successful navigation of challenges, the scope of the work and regional impact, cited ERC not only for constructing a new tunnel, but also taking on the rehabilitation of the existing tunnels and extending the Martin Luther King Freeway Extension with minimal disruption to traffic.

Boosting safety in the tunnels was a major impetus for the long-delayed project, ranked by the Hampton Roads Transportation Planning Organization as the region’s top priority. The overhaul gives the Downtown Tunnel a repaved road bed and new lights, ventilation and traffic control systems. “The new lights are 10 times brighter,” Woodsmall notes, adding that incidences in the westbound tube have dropped dramatically with the improved lighting. ERC will begin rehabbing the existing Midtown Tunnel once the new tunnel is opened. That work will repair leaks and tiles and bring the installation of a new ventilation system. Rehabbing all three tunnels carries a price tag of nearly $120 million.

“When that’s done, it will look very much like the westbound Downtown Tunnel,” Woodsmall says, referring to the soon-to-be rehabilitated tunnel. The project will eliminate the harrowing bi-directional traffic that motorists have put up with for years, since the new tunnel will carry westbound traffic from Norfolk to Portsmouth while eastbound traffic will use the old tunnel.

Along with improving transportation, the expansion has added to the region’s employment rolls. About 1,700 jobs have been created. Currently, between 700 and 725 people work locally on the tunnels project. They include more than 500 employed by SKW, the joint venture of Skanska, Kiewit and Weeks Marine that’s serving as the project’s design-build contractor. Also onboard are 120 ERC employees, 20 to 35 subcontractors and 75 ERC Customer Service Center employees. The remaining 1,000 jobs are positions within the community, industry and suppliers. SKW has subcontracted more than $311 million locally, while ERC has spent nearly $15 million locally to operate and maintain the infrastructures.

Then there’s the intrinsic value of the project’s on-the-job training program for about 70 carpenters, laborers, electricians, ironworkers and other craft workers. “When this project is over, the region will have a huge trained workforce for any future projects,” Marlow says.

Despite the good news, the project has not been without controversy. ERC officials hope motorists will focus on new jobs and shorter, safer commutes instead of tolls and tunnel closures. While there’s no dispute that an overhaul of the 52-year-old tunnel is long overdue, many motorists decried the tolls placed on the Midtown and Downtown tunnels in February 2014 before the project’s completion.

At that time, motorists with an E-ZPass paid $1 to drive through the tunnels during peak travel periods and seventy-five cents during off-peak times. Tolls went up 25 cents this January — to $1 and $1.25 — and will go up another 25 cents in 2016. Yet, it could have been worse. Until the state stepped in, the tolls were supposed to be $1.59 per trip for cars during off peak hours and $1.84 for peak drive-time hours (from 5:30 to 9 a.m. and from 2:30 to 7 p.m). These were the rates with an E-ZPass. They were higher if drivers opted for another payment method.

Compounding motorists’ frustration has been the regular nightly and weekend closures of the downtown tubes. Portsmouth business and political leaders have been especially incensed, fearing that the tolls could cause drivers from Norfolk and beyond to avoid the city.

“None of us, if we had our druthers, wants tolls anywhere,” says Portsmouth Economic Development Director Charles Rigney. “But we need to make transportation enhancements in the region to do a better job of linking communities together, and they do cost money.” Rigney adds that while some drivers may have shied away from using the tunnels when the tolls were first imposed, many have determined that taking alternative routes is just as costly in fuel or additional travel time.

Instead, Rigney says businesses have been more affected by weekend closures of the Downtown Tunnel’s eastbound tube. “It needs to be clearly understood when the tunnels are open and closed. If you miss that message and come to Portsmouth, you need to understand how to get to a secondary route.”

Combine periodic closures with the tolls, and frustration ensues for businesses and motorists. “Tolls only grease the skids to toll more facilities in the region,” Goodwin adds. “Eventually, people’s personal budgets won’t be able to justify paying tolls.”

On the flip side, Goodwin believes that as tolls increase, people living on the Norfolk side of the tunnels but working in Portsmouth will reconsider housing arrangements. “I can guarantee it will make people think twice about living in Virginia Beach and driving to and from work on the Portsmouth side. They’ll say why spend an extra $600 a year just to get to work.”

Goodwin says that situation will benefit new apartment complexes springing up in Portsmouth and northern Suffolk. “We’ve needed market-rate apartments for decades,” he adds. “We can obviously use this as a way to bank those apartments.”

Motorists hoped they had seen the last of the tolls on the Elizabeth River Tunnels when 25-cent fees were removed in 1986, 34 years after the Downtown Tunnel opened. Goodwin thinks it was a mistake to jettison tolls. “What the quarter toll could have done from 1986 to this point — we probably could have had another tunnel around 2000,” he says. “Now we’re playing catch up.”

Calling VDOT’s contract with ERC, which sanctioned tolls, the “worst deal I’ve ever seen,” Gov. Terry McAuliffe stepped into the fray shortly after taking office last year. He authorized the state to pay ERC $82.5 million to lower the tolls. Still, the tolls, along with annual increases, are destined to remain in effect until ERC hands operations over to VDOT in 2070. ERC’s contract with VDOT allows for annual toll hikes of 3.5 percent after year 2017 or the rate of the Consumer Price Index, whichever is higher, meaning that motorists could pay $21 to cross the Elizabeth River by 2070.

ERC has shouldered much of the criticism for the tolls, both for the amount and collection methods. Woodsmall, however, disputes the notion that ERC is lining its pockets with toll revenues. “Tolling is the funding source,” he says. “Without tolling, this project would not have been built. If we waited until the end of construction to put tolls on it, the toll would have been over $2.”

Depending on traffic, expenses and toll collection, ERC stands to accrue a 13 percent return on its $272 million equity contribution to the project. “That doesn’t occur until 2021 at the earliest,” Woodsmall notes. Meanwhile, the company must fund its operations, including maintaining the tunnel infrastructures. “The public doesn’t understand why we have to raise tolls, but going forward, it’s tolling that pays the debt and the operation and maintenance costs.”

Hampton Roads motorists likely will find it hard to escape tolls as the state tackles substantial highway projects throughout the region. They include the construction of a new eight-lane, high rise bridge in Chesapeake. “Those are very expensive projects,” says Virginia Transportation Secretary Aubrey Layne. “All are in the billions of dollars, and it will be a long time unless additional revenue sources are considered. That’s something we have to come to grips with.”

Nonetheless, Layne believes that pre-tolls should be taken off the table. “That’s a bad policy,” he says. “Motorists in Hampton Roads are paying for a facility that’s not expanded. Never again should we see pre-tolling of facilities.” Layne adds that motorists should always have the option to use either the tolled lane or a “free” lane, similar to those found in Northern Virginia. “If you want to pay, you join the HOT (high occupancy toll) lanes. If you don’t want to pay, you stay in the free lanes.”

Aside from tolls, the public-private partnership added another wrinkle to the public’s perception of the funding process, Woodsmall says. “It’s a new mechanism to this region, and there have been a number of challenges with all the entities to understand their role and responsibilities. But, I think we’ve finally overcome those challenges.”

Layne believes public-private partnerships are a viable procurement method, although he adds that the state should have initially invested more money in the tunnels project. “We’ve already done that in buying tolls down. It would have been much better to put the money in upfront and kept the tolls lower.”

Del. Chris Jones (R-Suffolk) agrees that tolls would have been much lower if the state had invested additional funding before the project got underway. Addressing the unpopular toll structure and the derailed project to build a new, tolled 55-mile leg of U.S. Route 460, Jones sponsored a bill during the recent legislative session that establishes new oversight and accountability for public-private partnerships in transportation projects. An advisory committee would review highway deals and determine if they serve the public interest, while VDOT would be required to identify high-risk projects and mitigate risks before significant funds are dispersed. “If this law had been in effect, the general terms of the tunnel toll agreement would have been released to the public before it was signed and certified to be in the public’s best interest,” Jones says. “Those terms of agreement should never have been signed. At the end of the day, they did a disservice to the region with those terms and conditions.”

Still, Jones believes the project will be a plus for the region. “The new tunnel will double capacity at the Midtown Tunnel,” he notes. “This is certainly going to be significant at peak traffic hours.”

In the end, ERC hopes that will be enough to dissolve any lingering animosity motorists have toward tolls and closures. “Our message is Elizabeth River Crossings is here to deliver,” Woodsmall says. “We’re doing our best to deliver and live up to the expectations of the project.”

>