Shifting trade winds

Virginia companies try to avoid being capsized by tariffs

Shifting trade winds

Virginia companies try to avoid being capsized by tariffs

Companies worried about a possible trade war are importing more goods, building their inventories before more tariffs take effect.

As a result, ports around the country — including the Port of Virginia — actually have seen a recent surge in cargo volume, which also has been driven by a strong economy and consumer demand.

But while Virginia’s maritime and logistics companies may be seeing a short-term increase in activity, the long-term consequences of a trade war could be widespread, damaging the entire national economy.

“This is such an ever-changing situation,” Huffman says of the escalation of trade tensions. “It’s difficult to keep our clients informed properly and to know what lies ahead … We don’t know how the wind is going to change. We can’t predict that.”

Short-term effects

International trade disputes have erupted in recent months, particularly between the U.S. and China. After President Donald Trump instituted steep aluminum and steel tariffs this spring, he added tariffs on more than $34 billion in Chinese goods.

Now the administration is proposing a far more wide-reaching wave of tariffs on 6,000 Chinese products worth more than $200 billion. At the same time, President Trump and Chinese leader Xi Jinping are meeting in November in hopes of easing tensions.

China is the Port of Virginia’s biggest foreign trading partner in total value and volume of exports and imports. The port, for example, handled $11 billion in imported goods from China last year.

China is not the only country in Trump’s crosshairs. Steel and aluminum tariffs also affect European Union countries, Canada and Mexico. Negotiations with Canada and Mexico over revisions in the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) are ongoing.

Effects of the trade disputes so far have been muted at the Port of Virginia and Virginia companies involved in the international supply chain.

Virginia soybean farmers already are feeling the pinch. In 2017, soybean farmers produced almost 26 million bushels of soybeans each year, accounting for $187 million in economic output. Much of the commonwealth’s soybeans are grown in the eastern and southeastern portion of the commonwealth. Since the spring, prices have dropped 16 to 20 percent. In July, President Trump announced $12 billion in relief for farmers affected by the trade war, but the funding still hasn’t been finalized.

While some importers are hedging against future tariffs, many are hoping the trade spats end soon.

That group includes Martinsville-based Hooker Furniture, which gets many of its products from China. “For now, we are monitoring the situation closely, evaluating the potential effects, communicating our concerns to Washington and our trade association, and, like everyone else, hoping cooler heads will ultimately prevail,” says Scott Prillaman, Hooker’s vice president of casegood operations.

Officials at Virginia Beach-based Stihl Inc., the U.S. headquarters of the German power-tool manufacturer, say it’s too early to measure the potential effects of more tariffs.

“We understand some of the issues the administration is trying to address with their recent decisions, and while we benefited from favorable tax changes earlier this year, any new tariffs on raw materials like steel and aluminum will have an impact on Stihl Inc.,” says its president, Bjoern Fischer. “As for long-term implications, we believe it is too early at this time to predict the full extent and implications of the tariffs.”

At the heart of the commonwealth’s maritime commerce is the Port of Virginia, which says so far it hasn’t seen any negative effects from tariffs. In its fiscal year ending June 30, the port handled a record 2.8 million 20-foot equivalent units [TEUs], the standard shipping measure for containerized cargo.

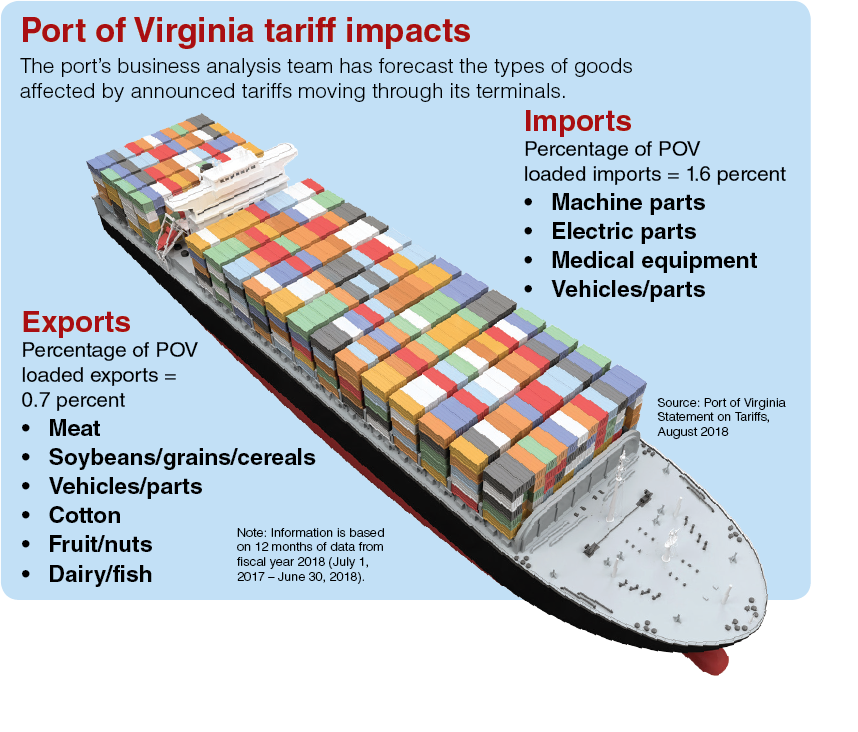

The port is analyzing the situation, but it says tariffs already announced will affect only a small percentage of cargo moving through its terminals.

“We are closely monitoring the current trade environment and the effects that additional tariffs are having on our business,” says Joe Harris, spokesman for the Port of Virginia.

The port does not have an analysis available on the impact of additional tariffs threatened by Trump. “We are focused on what we know, and we’re always concerned when there’s a shift in the trade policy,” says Harris. “But right now we have our eye on what’s happening, and we’ll have to address any changes as they come. Our focus at this point is completely on the expansion of our terminals.” (See related story on the port’s expansion).

Long-term harm?

But as tensions continue to rise, observers believe a trade war could harm the U.S. supply chain as well as the entire economy.

The 6,000 tariffs under consideration could have a much bigger impact.

Importers are nervous, Huffman of CV International says. Their worries are focused not so much on what is happening right now “but what the future holds … there will be a more far-reaching impact if the next round of tariffs goes into effect.”

Those tariffs, Huffman believes, could affect traffic at ports around the country.

The American Association of Port Authorities agrees. It says a trade war could hamper the $6 billion worth of goods that move through the U.S. seaports each day. The association says enacted and proposed tariffs would affect almost 9 percent of total U.S. trade by value and almost 14 percent of containerized trade.

Global Port Tracker says the biggest impact would be on West Coast ports, which handle the majority of Chinese trade. But a trade war still could make a big difference on the East Coast. Last year, about one-quarter of containerized cargo and one-fifth of exports handled by Virginia’s port were to and from China.

“If they think there’s more risk attached to that trade in the United States, they’re likely to look to other countries that they think are going to be more stable in terms of the tariff and trade barriers situation,” says Bingham.

Ultimately, a trade war’s biggest threat to the U.S. economy is uncertainty, he says.

If businesses are unsure of what their costs are going to be, executives may delay investment. If prices increase, consumers may be reluctant to spend. “That’s really the biggest-picture risk,” he says, “that you push the overall confidence and the attitudes of people engaged in commerce down enough that then you end up in a recession.”

Is a recession likely because of trade disputes? It depends, Bingham says.

“Do you take some of the members of the administration at their word that they truly are believers in free trade and all of this is an attempt to negotiate stronger positions for the United States?” says Bingham. “Or is this just somebody trying to punish certain countries because they’re our enemies … on a geopolitical basis? It’s hard to sort through all that to know what to expect.”

r