Preparation is essential in landing a business prospect

A presidential political campaign used to take months. Now it takes years.

By contrast, economic development projects that once required a year or more now are taking shape in a matter of just a few months.

The communities landing business prospects, and the jobs they create, are those that are prepared. They have invested in infrastructure and cleared away obstacles to compete a fast-paced race to rank among the finalists for a project and then seal the deal.

That’s one of the messages that Joe Hines is giving to elected officials around Virginia in speeches and webinars on economic development.

“Economic development is a long-term commitment,” Hines says. “Not an election-cycle buzzword.”

Hines speaks from experience. He is principal-in-charge of economic development with Timmons Group, a Richmond-based engineering firm. He has been involved in some of the biggest economic development deals in Virginia in recent years, including The Vitamin Shoppe’s distribution center in Hanover County, Rolls-Royce jet components plant in Prince George County, and two Amazon.com fulfillment centers in Chesterfield and Dinwiddie counties.

(In the interest of full disclosure, I should mention that Hines and I are not strangers. We were classmates in LEAD Virginia, a statewide leadership development program.)

Hines points out that, in part because of the slow recovery from the Great Recession of 2007-09, competition for business prospects is fierce and the speed of the site selection process is quickening.

For example, when Roll-Royce picked Prince George County for its jet components factory in 2007, the official announcement was made nine months after the company’s initial contact with the county. When Amazon.com and The Vitamin Shoppe came calling in 2011 and 2012, respectively, that time had been reduced by almost half, five months in each case.

One reason that the process is moving faster, Hines notes, is that, because of the Internet, 80 to 90 percent of the site selection search has been completed before the first contact with a local economic development office is made.

Once a company makes a decision to build a facility, construction can be speedy. On Aug, 31, 2012, then-Gov. Bob McDonnell announced The Vitamin Shoppe’s plans to build a 312,000-square foot distribution center in the Virginia Transportation Park in Ashland. Three weeks later, on Sept. 17, the site was fully graded. Two and a half months after the governor’s announcement, on Nov. 15, the walls of the building were standing. The building was substantially completed by the following April, and by mid-October 2013, the distribution center was fully operational, shipping products to Vitamin Shoppe stores.

The quickening pace of “time to market” on economic development projects means that potential sites must be ready to go for a city or county to be competitive. That means that utilities and infrastructure are in place on the site, and fast-track permitting is available.

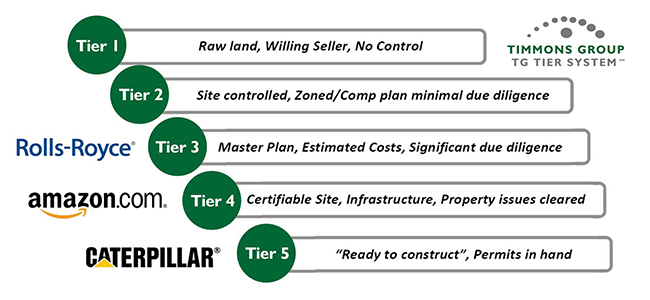

Hines has developed a multi-tier system (on a scale of 1 to 5) to evaluate site preparedness.

- The first tier is the lowest, with raw land and a willing seller.

- The site is controlled by the locality. It is zoned and part of a comprehensive plan, but minimal due-diligence has been conducted.

- The site is part of a master plan, costs of development have been estimated, and significant due diligence has been done.

- The site is certifiable (meaning it meets rigorous standards), infrastructure has been added, and all property issues have been cleared.

- The site is ready for construction and all permits are in hand.

As more preparation is done on a site, Hines says, the chance of success in landing a business prospect goes up, from less than 10 percent under the first tier to more than 90 percent under the fifth tier. He likens it to “gamblers odds”, noting that each level you move up gives you a higher likelihood of success.

Getting to the fourth or fifth tier, however, can require time and money. Southampton County spent more than eight years developing a Tier 5 tract, spending $13 million on infrastructure and $30 million on a wastewater system upgrade. The investment paid off. In 2011, the county closed a deal with Enviva Pellets for a $91 million wood pellet manufacturing facility on the site that would employ 72 full-time workers. The site also was a finalist for a Caterpillar factory that eventually wound up in Athens, Ga.

Events enter warp speed when a site is picked as a finalist. Usually only two or three potential sites are under consideration before the company makes its choice. Officials are given a short time (15 minutes in the case of Amazon.com) to make their best pitch and offer incentives. Hines urges officials to be ready to negotiate and respond quickly to all questions. Importantly, they also must “know your walk point,” the point at which the deal is too costly, and they must walk away.

“Work every deal until the end,” Hines notes. “You never know what you’ll learn about your site and community that will help you land the next prospect.” Mecklenburg County is a prime example. It lost out to North Carolina for an Apple data center only to land a Microsoft data center two years later.

The rewards of a successful deal can be game changing for a community. The Amazon.com deal, for example, represented a $135 million total investment in Chesterfield and Dinwiddie counties that eventually created 3,600 jobs.