On the rebound

Colleges, nuclear industry companies contribute to region’s economic recovery

Virginia Business //December 27, 2013//

On the rebound

Colleges, nuclear industry companies contribute to region’s economic recovery

Virginia Business //December 27, 2013//

Hundreds of people gathered near a high-traffic intersection in Lynchburg one morning in September as a grocer slowly sliced a 90-pound wheel of Parmigiano Reggiano cheese. When his knives cut the large wheel in half, cheers erupted.

Soon, shoppers — some of whom had waited in line since 5:30 a.m. — poured into the grocer’s new store to peruse 24,600 square feet of organic produce, fair trade coffee, fresh bread and other specialty foods.

This was the grand opening of Lynchburg’s first Fresh Market store, as well as Fresh Market Station, the city’s first new retail complex since 2010.

The story did not end there: Several other businesses opened in the shopping center, including a credit union, a Panera Bread restaurant and a Jersey Mike’s Subs franchise.

“I don’t know sales figures, but I know that we’ve got a normal amount of parking for a shopping center that size, and the parking lot is always full,” says Jeff DeHart, one of the developers who worked on the site. “I believe the retailers are doing very, very well.”

Retail is not the crown jewel of economic development. Government and business leaders primarily hunt for companies offering high-wage jobs. But many in Lynchburg saw the new shopping center as a sign that the economic recovery had really reached the city. Stores are opening, banks are lending, and the region has fostered an atmosphere that attracts investment from outside the city.

“Fresh Market doesn’t come to a place unless there’s a certain amount of traffic and household income,” says Bryan David, who was executive director of the Region 2000 Economic Development Council until December. He takes the store’s opening as one sign that the region has good things coming.

The Lynchburg region has been transformed in the past two decades. The population has grown by more than 20 percent since the early 1990s and now surpasses 250,000 people. Wards Road, once a quiet street, is a bustling business center with big-box stores and restaurants. Downtown Lynchburg is alive again with new shops, restaurants and loft apartments.

Meanwhile, the region’s economy has shifted away from low-skilled manufacturing to high-tech manufacturing, engineering, higher education and health care.

At the end of 2013, some of the region’s economic development leaders found their jobs in flux — the Region 2000 Partnership eliminated two jobs to create one chief executive position overseeing several programs, and the Lynchburg Regional Chamber of Commerce dropped its president position after the city of Lynchburg took its tourism program in-house rather than outsource it to the chamber. But despite looming changes in their organizations, these regional leaders expressed confidence about Lynchburg’s economic direction.

Pent-up demand

DeHart and his partners at Georgia-based S.J. Collins Enterprises started investigating possibilities for a shopping center at the corner of Lakeside Drive and the Lynchburg Expressway in 2007. The site has high traffic and a good customer base.

DeHart and his partners at Georgia-based S.J. Collins Enterprises started investigating possibilities for a shopping center at the corner of Lakeside Drive and the Lynchburg Expressway in 2007. The site has high traffic and a good customer base.

“There is a large population on the northwest part of town, and that part of town was underserved in quality retail,” DeHart says, noting that commercial real estate in that area has low vacancy and quickly fills up when it does have an opening.

“When we see things like that, it’s a clue that there’s some pent-up demand for quality retailers that need to be in the area,” he says.

The project was delayed during the recession, but when lenders opened to commercial projects again and retail chains started expanding, S.J. Collins broke ground. Fresh Market Station was more than 90 percent leased before it opened.

DeHart says Lynchburg’s colleges have made retail more viable in the city. While these institutions have been cited as a positive influence in Lynchburg for years, they are especially a boon now, says Rex Hammond, whose 15-year tenure as president of the Lynchburg Regional Chamber of Commerce ended Dec. 31.

“Much of the strength that we currently see in our numbers is a result of higher education — specifically, construction at Liberty University,” Hammond says.

Liberty’s growth

Once a small Bible college founded by the late evangelist Jerry Falwell, Liberty University now has about 12,500 residential students and more than 4,000 employees in the Lynchburg area. It also boasts more than 90,000 online students around the globe.

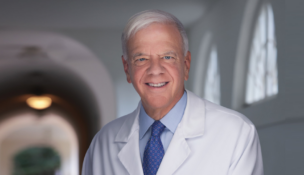

While growing its student body, the university has expanded its campus with new dormitories, recreational facilities, athletic fields and a health sciences center. That facility will include a college of osteopathic medicine that eventually will have 600 students and employ about 100 faculty and staff. In November 2012, Richmond-based Mangum Economic Consulting estimated that the university produces $139 million in net spending in the regional economy.

Other local colleges also have been growing, although in smaller numbers. Lynchburg College, which recently added a doctoral degree program in physical therapy, has about 2,700 students and 585 employees. Randolph College, a small liberal-arts institution, recently enrolled its largest freshman class in 25 years, bringing its student body to about 685. Randolph has about 340 employees.

Nuclear power players

High-tech firms also make their homes in Lynchburg and have helped sustain the economy. Two of the most noticeable are Areva and Babcock & Wilcox, major players in the nuclear industry that together employ more than 4,500 people locally.

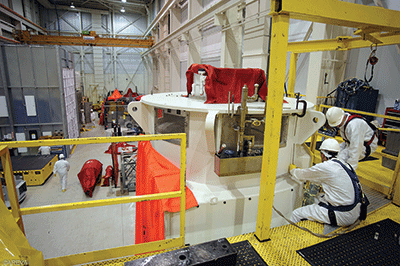

Since 2009, B&W has been developing mPower, a small modular nuclear reactor aimed at smaller-scale needs. The company built a test reactor in the Center for Advanced Engineering and Research in Bedford County so its engineers can run tests and prepare the mPower design for regulatory approval.

In November, B&W announced that it would seek equity partners to purchase the majority of its share in Generation mPower LLC, a joint development owned by B&W and Bechtel. Marshall Cohen, vice president for government affairs and communications, says a company B&W’s size needs more partners for a multibillion-dollar business venture. However, it is unlikely the business partners could sway mPower activity away from Lynchburg, he says.

“Lynchburg is the heart and soul of the mPower project,” Cohen says, citing B&W’s local talent pool and facilities. “Those are the things that really make us the world’s leader in the small reactor.”

Areva’s Lynchburg staff has worked on the engineering for that company’s new reactor, the U.S. Evolutionary Power Reactor. The France-based company also maintains a steady business servicing nuclear plants around the world.

In December, Areva announced plans to invest $26.3 million in its operations in the Lynchburg and Campbell County, designating those facilities as its Operational Center of Excellence for Nuclear Products and Services in North America.

The company will invest in highly advanced machinery and equipment to enhance research and development (R&D) capabilities and improve competitiveness in advanced manufacturing. Areva will receive an incentives package that includes a $350,000 performance-based grant from the Virginia Investment Partnership and local grants of $132,000 from Campbell County and $218,000 from Lynchburg.

Building a workforce

“I’ve recruited engineers to this area since 1994,” she says. “They love the idea of working for Areva and traveling internationally, but they never want to move away from here.”

People like the area for its cost of living — among the lowest in Virginia — a good environment for families, and outdoor amenities like the James River and the Appalachian Trail.

Still, Lynchburg’s high-tech companies face the same challenges that others face around the country: there are not enough people entering STEM fields (science, technology, engineering and mathematics).

Jonathan Whitt, the former executive director of the Region 2000 Technology Council, says workforce development was one critical need that local economic developers realized a decade ago. “We have the employers who want to stay here and want to grow. Their big issue has been, for a long time, workforce,” Whitt says. “A lot of our efforts have been focused on meeting that demand.”

After the reorganization changes at Region 2000, Whitt was tapped to lead the Roanoke-Blacksburg Innovation Network.

The resulting programs range from Lego robotics programs for elementary school students to Engineers PRODUCED in Virginia, a program that allows students to earn engineering degrees from the University of Virginia without leaving Lynchburg. The region also is home to a new Governor’s STEM Academy, which opened at Central Virginia Community College in the fall to give high school juniors and seniors more STEM education.

Local companies have worked with regional economic leaders in developing these programs, and Areva now employs the first five PRODUCED in Virginia graduates, Martin-Smith says. “Our philosophy is to develop candidate pools in the places in which we live and work,” she says.

Small businesses

Lynchburg has seen some small-business growth, too. One small business is the White Hart, a downtown cafe that closed its doors last spring. A few months later, it opened under a new owner who believed it could succeed.

“It was the community that made me want to buy the White Hart,” says Abe Loper, the new owner. “I knew that the White Hart already had a dedicated ‘fan base.’ … It was this local, grass-roots, community support that piqued my interest.”

Loper proved that the community was behind the idea by raising more than $11,000 in donations through the crowdfunding website Indigogo.

The local housing market has seen improvement, too. In the third quarter of 2013, the Roanoke-Lynchburg-Blacksburg market saw the largest home sales increase in the state: 2,230 homes sold, a 17.8 percent jump over the third quarter of 2012. House prices, however, crept up only 3.9 percent, to a median of $161,000, according to the Virginia Association of Realtors.

It is easy to see that the market has improved, especially in new construction, says Josh Ballengee, president of the Lynchburg Association of Realtors. “A lot of the homes are being purchased even before they are finished,” he says.

Economic hurdles

Despite these positive signs, the local economy has struggles, too. Joseph Turek, the dean of the School of Business and Economics at Lynchburg College, points out that the region’s job creation rates have slowed and were lower than almost every metropolitan area in Virginia in the first half of 2013.

A further troubling statistic: Lynchburg may need to add more than 7,800 jobs to keep up with projected population growth over the next decade. “If we don’t gun the economic engine and start creating jobs, and the state demographer is right, we’re going to be looking at some unhealthy unemployment rates,” he says.

Turek explained this analysis during the annual Economic Outlook Conference sponsored by the Lynchburg Chamber in October. Chamber leaders expressed concern but also a desire to act. They are working to devise research that would help identify weak points in the economy and chart a path to more growth. “I think it speaks very positively of the community that the business leaders want to identify the problem and find some kind of resolution,” Turek says.

Not all are worried about the numbers, though. Marjette Upshur, Lynchburg’s director of economic development, points out that much of the population growth consists of college students and retirees. “I’m not saying that there haven’t been struggles, but I think we’ve held our own,” she says.

Hammond, the former president of the Lynchburg Chamber, says it is clear that the economy is improving but needs serious attention to ensure that it continues on that path. “We need to deviate from passive job recruitment to more active programs where we solicit businesses to come to the Lynchburg region,” he says.

n