New tools in manufacturing increase efficiency, but will they make the industry cool?

Garry Kranz //September 27, 2013//

New tools in manufacturing increase efficiency, but will they make the industry cool?

Garry Kranz //September 27, 2013//

Brandon Lane knows firsthand how advanced technologies are reshaping manufacturing in Virginia. He runs Continental Corp.’s chassis and safety division in Culpeper, which makes engine parts, primarily for the automotive industry.

His 220 full-time employees are specialists, producing aluminum valve blocks for use in electronic stability-control systems. As competitors slashed capacity during a slowdown in the automotive market, the chassis and safety division did precisely the opposite. The Culpeper plant — part of German conglomerate Continental AG — spent more than $20 million installing high-tech machining equipment, a step that paid off when the auto market bounced back.

Lane says machining and other process-enhancing technologies have doubled the plant’s capacity during the past six years. Up to 18 computer-controlled machining centers are in operation at any given time, enabling technicians to make different types of valve blocks simultaneously, each one customized according to the specifications of the respective automaker. The system eliminates the need to halt production and swap out parts numbers before machining each product.

Continental recently installed an automated, high-pressure washing system that flushes aluminum chips and other impurities from the valve blocks. Inspection is highly computerized as well, including “vision systems” that measure micron-size tolerances of the various machined features, including ports for attaching solenoid valves, pump motors and pistons.

To ensure nonconforming valve blocks aren’t shipped out, robots pick each item off the assembly line and perform a series of secondary quality checks before stamping it with a two-dimensional bar code for traceability. The robots are used to support the eyeball checks made by Continental employees.

Continental’s story is a microcosm of Virginia’s evolving manufacturing sector and indeed of manufacturers in the U.S. in general. From heavy equipment-makers to biotech firms to food processors, Virginia companies are using advanced techniques to get leaner and meaner. High-powered computing equipment is eliminating much of the drudgery traditionally associated with manufacturing jobs, while at the same time driving up demand for cognitive thinkers and out-of-the-box problem solvers.

Virginia is seeing growth in new industries even as established sectors try to stay ahead of macroeconomic trends. One notable achievement: Virginia added a crown jewel last year with the launch of the Commonwealth Center for Advanced Manufacturing, or CCAM, a collaborative research effort involving 15 companies and three Virginia universities. (See related story on CCAM.)

The evolution here is part of a national trend linked to U.S. free-trade agreements. American manufacturers have been outsourcing unskilled jobs overseas in recent years to take advantage of cheap and abundant labor. Virginia has not been immune: More than 230,000 manufacturing jobs have vanished during the past two decades, mostly related to the demise of the apparel, furniture and textile industries, according to the Virginia Manufacturers Association, a Richmond-based trade group.

The shift has been away from labor-intensive jobs to production of higher-value goods, particularly exports, says VMA President Brett Vassey. “That’s where our transformation has come in the past 15 years or so. Automation is bringing labor costs down and driving productivity through the roof,” he says.

Despite the staggering decline in jobs, Virginia’s 6,000 manufacturers employ more than 239,000 people, making it the seventh-largest segment of the state’s economy, according to the Virginia Economic Development Partnership, the state’s business-recruitment agency. Manufacturing jobs also pay well: The average annual wage of $53,461 is $2,800 higher than the average for all other occupations, VEDP says.

To manufacture its line of handheld power tools, Virginia Beach-based Stihl Inc. needs employees who are comfortable working with robots, advanced materials and complex computer systems. “The sloppiness of unskilled labor is gone forever from modern manufacturing. We presume humans like to use their brains in their work,” says Simon Nance, Stihl’s manager of learning and development.

The big change in recent years is that most manufacturing jobs now require an associate’s degree or industry certification, says Mike Lehmkuhler, a vice president with VEDP. “These are not boring repetitive jobs anymore. People need a pretty high skill level to operate and troubleshoot the sophisticated equipment,” he says.

Adapting on the fly

Continental is taking steps to provide targeted technical training to career-minded employees. It launched an apprenticeship program several years ago for aspiring maintenance technicians, whose job is to keep the production machinery humming. Lane says five employees have earned their two-year degrees and achieved certification as journeymen through the program. Continental helped design the coursework, which was delivered by faculty at Germanna Community College in Fredericksburg. A similar apprenticeship program is being started for machinists.

“For us, providing technical training to Continental employees is a much better solution than trying to recruit from outside the company,” Lane says.

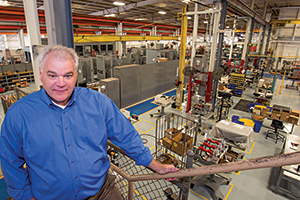

manufacturers must be able to adapt to tumultuous changes.

Photo by Mark Rhodes

Adapting to tumultuous changes in manufacturing is necessary for survival, says Howard Broadfoot, the vice president of operations at Bristol-based Electro-Mechanical Corp. The 55-year-old company makes and installs huge electrical-distribution systems used at underground mines, utilities and commercial facilities. The equipment includes transformers, substations and switch gears.

While larger competitors like General Electric Corp. angle for multibillion-dollar projects, Broadfoot’s company specializes in jobs in the $2 million range. “That’s our sweet spot,” he says.

Until recently, about half of Electro-Mechanical’s annual revenue came from equipment sold to the mining industry. With the coal industry grappling with tougher environmental regulations and competition from natural gas, demand has fallen dramatically.

Fortunately, the company was prepared. Russell Leonard, the second-generation president of the family-owned business, charted a new strategic course in 2008, diversifying into untapped markets. Electro-Mechanical found a ready-made customer base in the booming data-center market. Equipment sales to power-hungry data centers are surging, accounting for roughly one-quarter of company revenue last year, Broadfoot says, helping to offset the decline in coal-related business.

Anchoring the change in philosophy is a heightened focus on research and development. The company launched a research division to innovate products, often in collaboration with customers. The advanced tools include three-dimensional printers used to design rapid prototypes. Broadfoot says it enables the company to custom-engineer product designs based on the needs of individual customers. Client companies are invited to Electro-Mechanical’s facilities to examine its product research up close, sometimes even requesting follow-on projects that fill a niche.

“We’ll tell the customer to go have lunch, and by the time they return, the changes are made. We hand them a 3-D printout that indicates the size of the equipment, the functionality and so on,” Broadfoot says.

This close collaboration with customers is a keystone to winning new business and retaining existing work. Usually, companies jealously guard their intellectual property, but Broadfoot says Electro-Mechanical wants its customers — and prospective customers — to get a firsthand look at products under development. (The companies are required to sign nondisclosure agreements.) “Showing customers a product they’ve never seen before is an incredible selling tool,” Broadfoot says.

In addition, Broadfoot says, construction is under way on a 10,000-square-foot Research and Technology Center, which will enable a “full transition” of R&D staff to a dedicated facility.

Electro-Mechanical developed a proprietary production-management system that is patterned after the Toyota Production System of Toyota Motor Corp., widely credited with pioneering lean techniques. Billed as a “visual factory,” the system consists of multiple information centers in the company’s manufacturing facilities. Employees (and customers) can use the information stations to track a product’s progress through each phase of the manufacturing process.

“Safety, quality, raw material, headcount and any other issue that may impact a specific order is documented and available for all to see, and more importantly, they can offer suggestions for improvement. Not a new concept, but it’s one we do very well at Electro-Mechanical,” Broadfoot says.

Electro-Mechanical also devoted about 100,000 hours to retraining employees in advanced techniques. Broadfoot estimates the company spends about $1 million annually on engineering and advanced technical training but says the money and time is worth it. “We’re not preparing for tomorrow. We’re preparing for what the next generation will bring.”

Making ‘bugs’ and coffee

While Continental and Electro-Mechanical make larger pieces of equipment, Salem-based Novozymes Biologicals Inc. turns the stereotype of manufacturing on its head.

Instead of assembly-line workers performing repetitive tasks, Novozymes employs research scientists working in sparkling laboratories. The white-frocked researchers use proprietary technologies to isolate, test and produce class-1 microbes used as ingredients in environmentally friendly cleaning products. Known as the “good guys” of microorganisms, the non-disease-carrying germs provide a green alternative to chemical-based products. “We grow bugs,” says Bob Blankenship, the company’s quality, environmental and safety manager.

The biologicals group in Salem is a subsidiary of Novozymes AS, a Danish company with $2 billion in global revenue. Blankenship’s outfit did about $50 million in business in 2012, growing microbes from naturally occurring substances found in soil, water and plants. About half its business in Virginia stems from the manufacture of microbe-based cleaning products for consumer and commercial uses, including household carpets and industrial grease traps.

Two methods are used to grow the microorganisms: submerged fermentation and solid-state production. In the first method, huge fermentation tanks are filled with several thousand gallons of water, with food sources and oxygen added to provide the right growing environment. In the second method, microbes are “grown dry” by being placed in a climate-controlled chamber.

“We invested in some of the most advanced technologies available to completely change our manufacturing processes,” Blankenship says, although he declined to provide specifics, citing competitive reasons. “We’re producing more bugs at the same time that we’ve reduced our water consumption by 42 percent, and that’s a huge cost savings.”

Novozymes has 170 full-time employees in Virginia. Most of them have advanced degrees, and about half have earned doctorates. Even workers in lower-level jobs as operators need at least a high school diploma, although company-sponsored industry certifications or relevant training and experience are commonly required. “We can’t just bring people off the street to grow microbes,” says

Blankenship, adding that Novozymes has developed “strong relationships” for workforce training with Virginia Tech, Radford University, Ferrum College and Virginia Western Community College.

Novozymes globally invests 14 percent of its profit in research and development, and the Roanoke Valley — where the company operates seven facilities — is a hub of innovation. Novozymes recently opened a new greenhouse in Roanoke County’s Center for Research and Technology, which will cultivate microbes for its growing bio-agriculture business.

“Our scientists travel all over the world to find microbes and bring them to our labs to culture them and see what they’re capable of,” Blankenship says. Once the applications have been tested, it paves the way for full-scale production of specialized products at other Novozymes plants in Canada, China and Europe.

But the food-and-beverage industry may be the best example of the dynamic transformation taking place in Virginia. Since 1980, food processors have contributed nearly 20,000 jobs and have sunk $4.7 billion in land, facilities and equipment, making it one of the fastest-growing segments of Virginia’s economy. More than one-third of the jobs (7,729) and roughly half the spending have been added since 2003, according to figures from VEDP.

Through August this year, nearly 20 food-product manufacturers have announced plans for $510 million in capital investment in Virginia that is expected to create more than 1,100 jobs. One of the biggest deals in this sector in recent years involved a 2011 announcement by Green Mountain Coffee Roasters Inc., which is ramping up a 330,000-square-foot manufacturing and distribution plant in Isle of Wight County. The factory will make the single-serve disposable containers used in Keurig coffee makers. The Waterbury, Vt.-based chain said it plans to invest $180 million over five years, possibly employing up to 800 people during that time.

Competition for the jobs is expected to be fierce. An initial job fair for the first 100 jobs this year attracted more than 1,200 applicants from as far away as North Carolina, says Lisa Perry, director of Isle of Wight’s economic development department.

She says Isle of Wight’s coup represents some good news after the closure of an International Paper plant near Franklin in 2011, putting 1,100 people out of work. “We were able to quantify that we had an available workforce with the skill sets Green Mountain needs,” Perry says.

In reality, though, Virginia manufacturers may have a tough time competing unless the pool of trained production workers gets a lot deeper. Manufacturing still suffers from an image problem, with most Americans equating the industry with smokestacks, dimly fit factories and dead-end jobs. Manufacturing ranked fifth of seven career choices in a poll of 1,000 U.S. adults, according to a joint report in 2012 by consulting firm Deloitte and The Manufacturing Institute, a Washington, D.C., think tank. Only financial services and retailing were viewed less favorably.

In Virginia, the image issue is approaching crisis mode. U.S. Census data indicate roughly 15 percent of Virginia’s manufacturing labor force could retire as soon as 2016, but most young people aren’t considering manufacturing as a career, says Katherine DeRosear, director of workforce development at the Virginia Manufacturers Association.

“Our manufacturers are terrified that they’re about to lose vast institutional knowledge and be unable to replace it,” DeRosear says.

Seeking to reverse the tide, the VMA has launched outreach efforts to burnish the industry’s image, including its Dream It, Do It Virginia and the Military2Manufacturing initiatives (see related story).

The industry’s future hinges on those efforts. Virginia probably will never regain most of the 230,000 jobs that disappeared with the decline of old-line industries. To survive, companies will need to invest in new talent and new technologies.

Continental offers an object lesson. Although the auto-equipment maker took its lumps during the downturn, failure was not an option. “We installed the new equipment because we expected the North American auto market would rebound,” says Lane, the plant manager. “And when it did, we were able to quickly respond while our competitors couldn’t.”

-