GO Virginia

Regional initiative prepares to pivot from planning to action

GO Virginia

Regional initiative prepares to pivot from planning to action

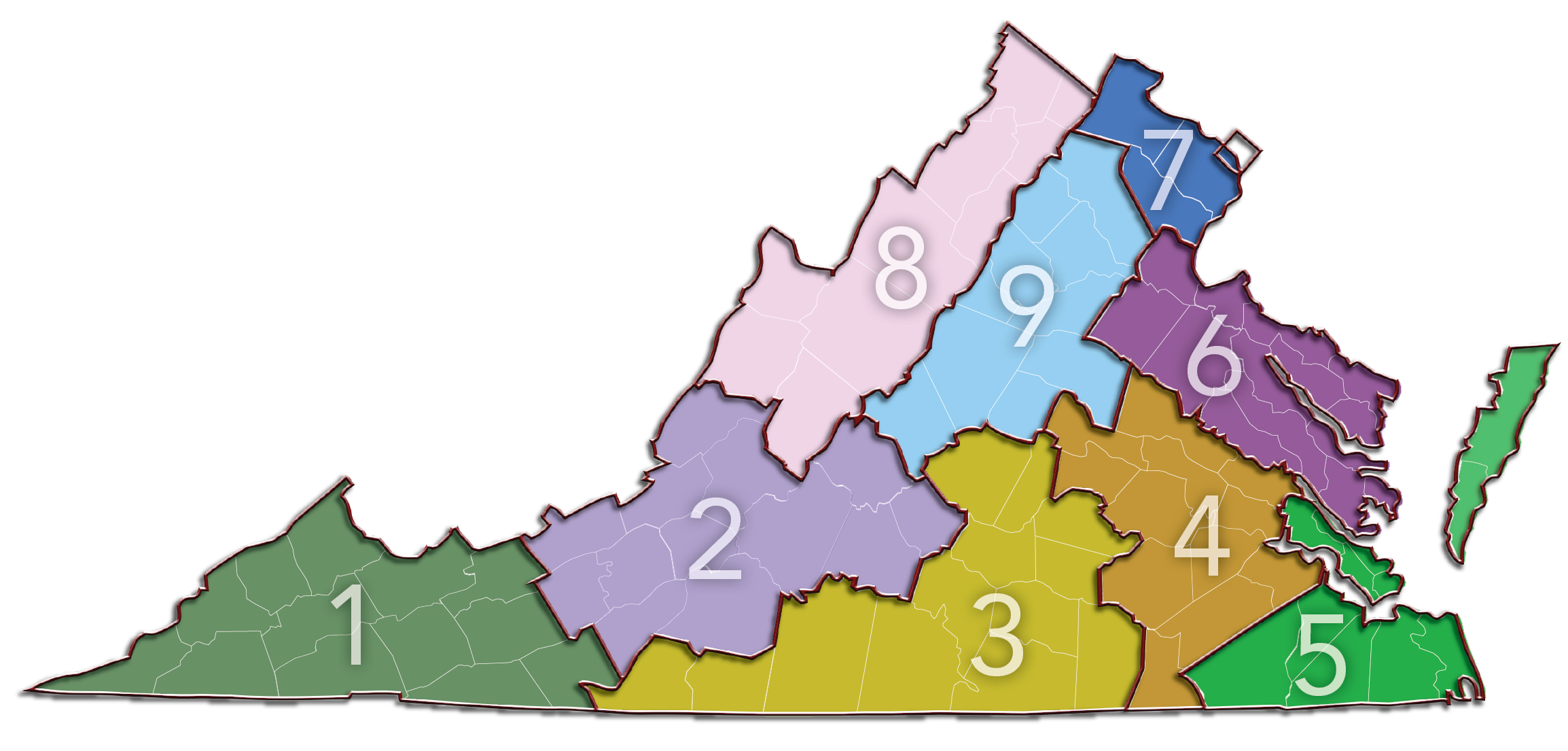

Southern Virginia, Region 3, is the largest in land area of the nine regions making up GO Virginia, the $28 million initiative to promote economically sustainable growth across the commonwealth.

But the region, which covers a wide swath of the state’s Southside, is also the smallest by headcount, with an aging population and a 7 percent employment decline since 2006.

So Region 3 business and community leaders see the need for workforce recruitment and training in traditional fields of health care and skilled trades, but also for collaborative new approaches to developing cyber infrastructure.

By contrast, Region 7 in Northern Virginia already is a key driver of the state’s economy. Nevertheless, the region is heavily dependent on federal spending, and its workforce is insufficient to meet the needs of technology-related occupations.

This economic kind of soul-searching is the pivotal first step for accessing grant funding under GO Virginia — short for the Virginia Initiative for Growth and Opportunity in Each Region.

The plans represent 1,800 pages of “deep thinking,” says GO Virginia Board Chairman John O. “Dubby” Wynne, but no head shaking about the challenges ahead.

“We are still a startup,” Wynne says. “But we know what needs to be done.”

$400,000 to each council

GO Virginia, established in 2016 by the General Assembly with funding over two years, is administered by the state Department of Housing and Community Development (DHCD).

The program awarded each council $400,000 to develop a growth and diversification plan to assess the current economic landscape, workforce gaps and opportunities for collaboration.

Approval of the plans will allow the councils to receive grants designed to support regional ventures with a goal of making the state’s economy less dependent on the federal spending.

Information and emerging technologies represented the common industry cluster identified by all regions. Likewise, talent and workforce development was seen as a key strategy to reach goals.

The 24-member GO Virginia board approved criteria for reviewing grant applications based on the priorities submitted by each council. Board members will work in small teams with the regional groups as the grant requests are formulated.

The initial round of grants, which will total $10.9 million, are to be awarded by the end of the year to all regions proportioned on a per-capita basis, according to Christopher D. Lloyd of McGuireWoods Consulting.

A second round of grants totaling $11.3 million will be awarded through a statewide competitive process early next year. Another $250,000 also is available for research and administrative overhead if necessary.

Creating higher-paying jobs

GO Virginia’s stated purpose is “to create more higher-paying jobs through incentivized collaboration and out-of-state investment that diversifies and strengthens the economy of every region.”

The geographical regions were created for organizational and administrative purposes, not because of their similarity. Some are as diverse as the state itself.

Region 6, for example, includes Fredericksburg, the Middle Peninsula and the Northern Neck, three areas that have significant differences in economic performance.

The region also sees “daily negative out-flow of 75,412 workers” commuting to other regions. One of the plan’s goals is to reduce the percentage of commuters.

Region 4, meanwhile, includes the growing Richmond area and is attracting commuters, drawing a net inflow of 40,717 workers. The region is home to nearly 1.5 million people with average annual wages of more than $50,000.

But the region also includes areas where poverty has risen, including Petersburg, Hopewell and Greensville County.

Included in the region’s goals is an effort to stimulate growth in bioscience, manufacturing and logistics using advanced technology.

Broadband infrastructure

Region 1 in the southwest corner of the state historically has been dependent on its natural resources, such as coal, timber and natural gas, which have brought boom and bust times.

The Appalachian Mountains, which run through many of the 13 counties and three cities in the region, highlight its beauty but also its remoteness, making it difficult for residents to reach jobs.

Among its goals is an effort to leverage broadband infrastructure to help residents work remotely while also promoting the region as a “culture of wellness.”

Likewise, Region 5 plans to capitalize on unique attributes of Hampton Roads. Flooding, for example, has created a regional emphasis on water technology. Although second to Northern Virginia in population and economic output, the region is not growing as rapidly as the state or the country as a whole.

Like Northern Virginia, Region 5’s economy is heavily dependent on the federal government. Plus, overreliance on a small set of large firms in key industries — including shipbuilding and advanced manufacturing — has left the region vulnerable.

The Region 2 plan highlights contributions of its 23 institutions of higher learning — including Virginia Tech and Radford University — but also identifies workforce educational gaps.

The region, which includes Lynchburg, the New River Valley and Roanoke-Alleghany areas, will target four interrelated industries for growth: manufacturing; life sciences and health care; food and beverage processing; and emerging technology and IT.

Region 8’s plan cites its “shining examples of American countryside,” such as the Shenandoah National Park, and the area’s agricultural legacy. But the plan also sees continued strength in the region’s tradition of light manufacturing and potential to increase the depth of the entrepreneurial ecosystem.

The plan for Region 9, which includes the University of Virginia, also emphasizes startups established from commercializing university-based research.

The region lacks national-level brand recognition for its innovation assets, something comparable to North Carolina’s Research Triangle Park, the report says.

It suggests such branding for the U.S. 29 Corridor, starting in Charlottesville with U.Va. research, continuing northward to include the data centers in Culpeper County and reaching into Fauquier County with its defense and cybersecurity industries.

A goal of GO Virginia is “to break down silos around localities” that can hamper economic growth, Wynne says. The work devising the plans already has fostered collaboration, he says, bringing together “people who formerly didn’t talk” to figure out how they can partner on projects.

“We’ve started a spirit in the state” for collaboration, he says.

>