Focused on research

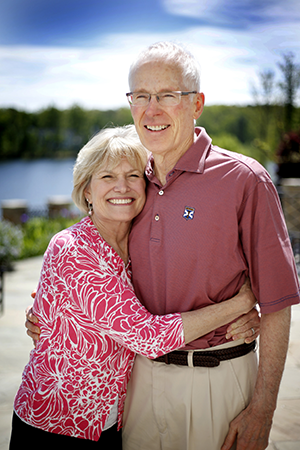

Sherry Sharp’s philanthropy is devoted to finding a cure for Alzheimer’s

Focused on research

Sherry Sharp’s philanthropy is devoted to finding a cure for Alzheimer’s

As Richard Sharp was driving home from dinner one night with his wife, Sherry, he unintentionally turned in the opposite direction of their Richmond-area house.

“He didn’t forget how to get home,” says Sherry Sharp. “It was that he lost the ability to understand what was left and … right … what was up and down.”

Richard Sharp’s trouble with directions that night, roughly a decade ago, was one of the first signs that the co-founder of Glen Allen-based CarMax and former CEO of Circuit City had a rare, early-onset type of Alzheimer’s disease. He wouldn’t be officially diagnosed as having the disease until approximately three years later. Alzheimer’s eventually would leave him unable to perform simple functions, like sitting calmly in a chair.

“He would become panicked because he felt like he was falling,” Sherry Sharp recalls.

In June 2014, at age 67, Richard Sharp died from Alzheimer’s. He was one of more than 93,000 people who succumbed to the disease that year, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). An estimated 5.5 million Americans suffer from Alzheimer’s, the sixth-leading cause of death in the U.S.

Alzheimer’s is a type of dementia that gradually destroys the brain, leading to memory loss and the disruption of many physical functions. In the advanced stages of the disease, the brain cannot tell the body what to do, making it difficult for some sufferers to walk, swallow or even breathe.

There currently is no cure for Alzheimer’s. Sherry Sharp is working to change that. Her causes include the Massachusetts-based Cure Alzheimer’s Fund (CAF), a nonprofit that funds Alzheimer’s research, and the Rick Sharp Alzheimer’s Foundation, launched last year to raise funds to help eradicate the disease.

“I actually had a chance to discuss [CAF] with Richard before he died, and he was very onboard with how they function,” she says. “His endorsement is what encouraged me to become a director in December 2014, after [he] passed away.”

Last summer, the Rick Sharp Alzheimer’s Foundation raised half a million dollars for CAF through its first event, the Rick Sharp Classic golf tournament and auction. The event will be held again June 12-13 at Independence Golf Club in Midlothian. This time, Sherry Sharp hopes to raise $750,000 for CAF.

Inadequate funding?

Since 1999, she has given countless hours and millions of dollars to Alzheimer’s research, though she prefers not to disclose how much. The majority of her gifts, since joining the CAF board in 2014, have been to that nonprofit.

Advocates and scientists in the field say inadequate research funding is a major barrier to finding effective treatment and a cure. Current drugs help mask symptoms but don’t treat the disease or delay its progression, according to the Alzheimer’s Association.

George Bloom, a professor of biology and neuroscience at U.Va., who is one of three researchers at the university who have received funding from CAF, says, “The lion’s share of [Alzheimer’s research] funding comes from [the National Institutes of Health], which has been steadily increasing its contribution to Alzheimer’s research over the last handful of years, but it’s still, in my opinion, grossly underfunded at NIH and elsewhere.” Bloom, however, notes that his lab currently is well funded.

The fiscal year 2017 budget, which ends Sept. 30, includes an additional $400 million for research on the disease. That increase brings NIH’s funding for Alzheimer’s research in 2017 to nearly $1.4 billion, despite a proposal by President Trump’s administration to cut the agency’s total funding by $1.2 billion for the fiscal year. Trump’s proposed budget for fiscal year 2018, set to start in October, recommends slashing even more money from NIH, $5.8 billion. (An updated version of the budget proposal had not been released when this issue went to press.)

Rising cost of care

Threats to federal Alzheimer’s funding means private donations will be even more critical, Sherry Sharp says. Even if the disease hasn’t impacted people personally, afflicting a family member or a friend, it will affect their pocketbooks, she says. The Alzheimer’s Association estimates the nation will spend $259 billion this year caring for people with the disease. Medicare and Medicaid are expected to cover the majority of those costs. The number of Americans age 65 and older with the illness could rise to 13.8 million by 2050. The cost of care for patients with Alzheimer’s and other dementia is expected to reach $1.1 trillion that year.

CAF funding has aided the Alzheimer’s-related research of Bloom and John Lazo, a pharmacology professor at U.Va. and adjunct professor at the Roanoke-based Virginia Tech Carilion Research Institute. The researchers are using $200,000 from CAF to reproduce conditions found in the brain of an Alzheimer’s sufferer using cells from humans and mice. Bloom and Lazo hope their research will eventually allow them to test new treatment options for Alzheimer’s and understand the disease better.

“I can say without any doubt whatsoever that, without this funding, our labs’ efforts to try to approach this problem would be crippled,” says Lazo. “It’s allowed us to do some things that are bold and … that aren’t easily funded by the traditional, slow-moving, federal government-supported research.”

Sherry Sharp would like to see a cure in her lifetime. If she dies before that happens, she would like to know progress is being made. She likens the money now being invested in Alzheimer’s research to putting out a house fire with a bottle of water.

“The most difficult thing about the disease is getting the awareness out to everybody and saying, ‘Let’s pull together,’ because I can’t do it on my own,” she says. “We need everybody to be on board.”

P