Empowering a region

UMW tracks area’s growth as it makes key investments

Robert Burke //September 29, 2015//

Empowering a region

UMW tracks area’s growth as it makes key investments

Robert Burke //September 29, 2015//

Curry Roberts used to see the Fredericksburg region as akin to Harrisonburg in the Shenandoah Valley — a medium-size city with a university in the middle that helps to boost its economic growth.

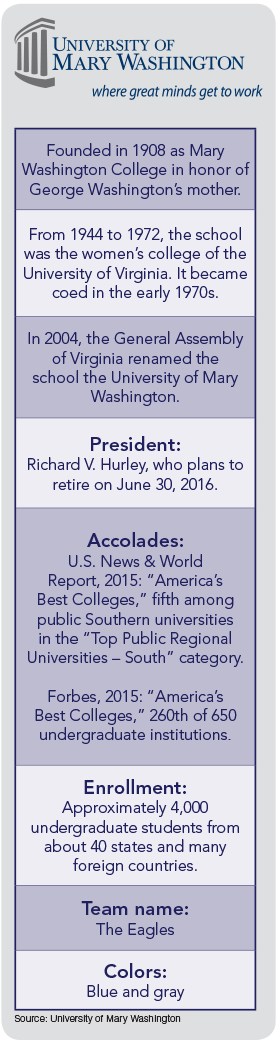

Harrisonburg has James Madison University and Fredericksburg has the University of Mary Washington, so there’s a similarity. But now Roberts, who is executive director of the Fredericksburg Regional Alliance, thinks that he was following the wrong model. That realization came last winter after he asked a handful of economic development veterans from around the state to evaluate the FRA’s strategy.

The Fredericksburg area should be competing with the state’s bigger regions, they said. “We really need to start looking at ourselves as the fourth major metro area in the urban crescent,” Roberts says, referring to the swath of development that runs from Northern Virginia down through Richmond to Hampton Roads. That is where much of Virginia’s economy resides, and Fredericksburg is right in middle of it, halfway between Richmond and Washington, D.C., on the Interstate 95 corridor.

Northern Virginia has George Mason University in Fairfax, and Richmond has Virginia Commonwealth University and the University of Richmond. Hampton Roads has Old Dominion University. “We have Mary Washington. We wouldn’t be in that game without them,” he says.

‘Ripe with opportunity’

As this region of nearly 350,000 people continues to grow, UMW has shown that it wants to lead efforts to build the local economy. It is already a major local employer, with about 850 people working at its three main locations, and an annual budget this year of $110 million. The main campus in Fredericksburg has 4,000 students and just enrolled its largest freshman class ever. It also has campuses in Stafford and King George counties.

Plus, the university hosts the region’s economic development programs. In 2011 UMW launched a partnership with the FRA and formed the University Center for Economic Development. UMW President Richard Hurley has been pushing the school to take a lead role, saying the region “is ripe with opportunity to further develop economically, and I would like to see UMW become a key player in that effort.”

Plus, the university hosts the region’s economic development programs. In 2011 UMW launched a partnership with the FRA and formed the University Center for Economic Development. UMW President Richard Hurley has been pushing the school to take a lead role, saying the region “is ripe with opportunity to further develop economically, and I would like to see UMW become a key player in that effort.”

Two years ago Hurley and UMW hosted an event, the Transformation 20/20 Regional Economic Development Summit, that was part of an ongoing effort to come up with a plan for the region’s economy. And in August, UMW and the FRA along with the Fredericksburg Regional Chamber of Commerce created the Center for Economic Research. That new initiative, which is based in the school’s economics department, is designed to give the region a more detailed picture of what it can offer potential employers.

Other regions turn to local universities for similar economic data, Roberts says. Both ODU and GMU have major economic research centers, and until now the Fredericksburg region has had to depend on experts from outside the region for that information. When prospects come looking at the region as a potential location, “I don’t want to hand them a study done at George Mason,” he says.

The new research center’s first task is to study the region’s commuting workforce, which is a topic the region has struggled with for a long time. Roberts says there are about 70,000 people who commute to jobs outside the region, primarily to Northern Virginia and the Washington, D.C., region.

Part of the reason why a local research effort might produce better results is that it will take some legwork to get details on these commuters. Tim Schilling, a UMW economics professor who is leading the research center, says the Fredericksburg region is divided between multiple metropolitan statistical areas, or MSAs. “When you look at nationally collected data like that you kind of have to sort through it and do the best you can,” he says.

Part of the reason why a local research effort might produce better results is that it will take some legwork to get details on these commuters. Tim Schilling, a UMW economics professor who is leading the research center, says the Fredericksburg region is divided between multiple metropolitan statistical areas, or MSAs. “When you look at nationally collected data like that you kind of have to sort through it and do the best you can,” he says.

The FRA has commissioned studies on the topic in the past, says Roberts, but there wasn’t enough detail. “We need to pull our data out and create or own regional report, and Mary Washington has the capacity to do that,” he says. “We’ve got a highly skilled workforce, but we don’t know it to the granular level” — answering questions such as, how many electrical engineers live in the region but commute elsewhere? “We may find that there’s a skill set where we’ve got a critical mass.” The study is expected to be completed by spring 2016.

Foundation projects

Outside of Fredericksburg, UMW has been making a number of investments. In 2012 the school opened the Dahlgren Center for Education and Research, a 42,000-square-foot facility just across U.S. 301 from the Naval Surface Warfare Center. It has classrooms, computer labs, meeting space and a 220-seat auditorium. A variety of graduate-level course options are available there, through on-site and distance learning. The center has partnerships to provide courses with many of Virginia’s major universities, along with the Naval War College and the Naval Postgraduate School.

Perhaps the school’s most visible impact on the local economy has been through the UMW Foundation, a tax-exempt organization that currently holds more than $50 million in real estate assets. In late 2007 the foundation bought an aging 23-acre shopping center directly across U.S. 1 from the main UMW campus and has since been redeveloping the property as a mixed-use project. It’s now called Eagle Village, after the UMW mascot.

Since then the foundation has built the $115 million Eagle Landing project, which has student housing, a parking garage, Class-A office space, and retail and restaurant space. The shopping center is connected to the main campus by an enclosed pedestrian bridge over U.S. 1. The foundation also brought in a five-story Hyatt Place hotel, which opened last year, and the Children’s Museum of Richmond, which opened its first location outside of the Richmond region.

Jeff Rountree, the foundation’s executive director, says the redevelopment of the rest of the shopping center will happen as the university needs it. The first phase happened because “they needed more apartment-style housing and they needed upscale” office space, he says. “So now what we have to do is simply hold on until they are ready.”

But the foundation is still making tentative plans for what it might do next. “One idea that keeps popping up is … a first-class performing arts center. And UMW is always involved in that discussion.” That could one day be built in the older portion of the Eagle Village shopping center, he says. Plus, the foundation owns about 600 acres of land along U.S. 17 in Stafford, which at some point could be developed by the foundation or by the private sector.

Rountree says it’s way too early to know what might happen there, but the foundation and UMW are ready. “A lot of times I’ll be asked by my board, ‘What are we doing with all this land?’” He tells them that without the land, the school can’t grow. “The more land you have, the better,” he says. “We’re very entrepreneurial.”

C