Drawing a line

Redistricting cases before the Supreme Court question the General Assembly’s intentions

Tim Loughran //August 30, 2016//

Drawing a line

Redistricting cases before the Supreme Court question the General Assembly’s intentions

Tim Loughran //August 30, 2016//

For the second straight term, the U.S. Supreme Court plans to examine how the Virginia General Assembly drew the state’s election district maps after the 2010 U.S. Census.

For the second straight term, the U.S. Supreme Court plans to examine how the Virginia General Assembly drew the state’s election district maps after the 2010 U.S. Census.

The cases could have longlasting effects on Virginia elections, but political observers don’t expect either to dramatically shift the balance of party power in the U.S. House of Representatives or the state House of Delegates.

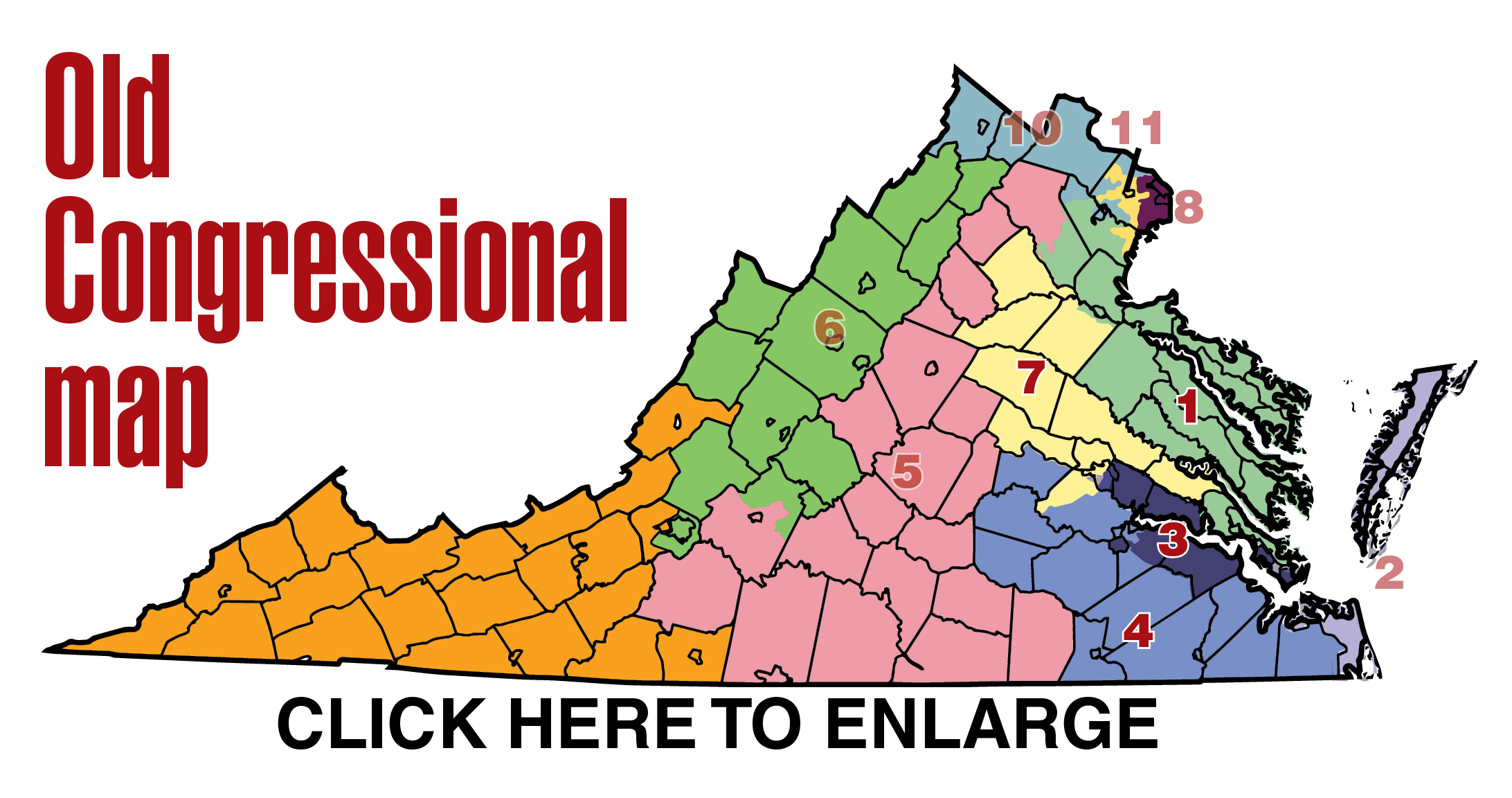

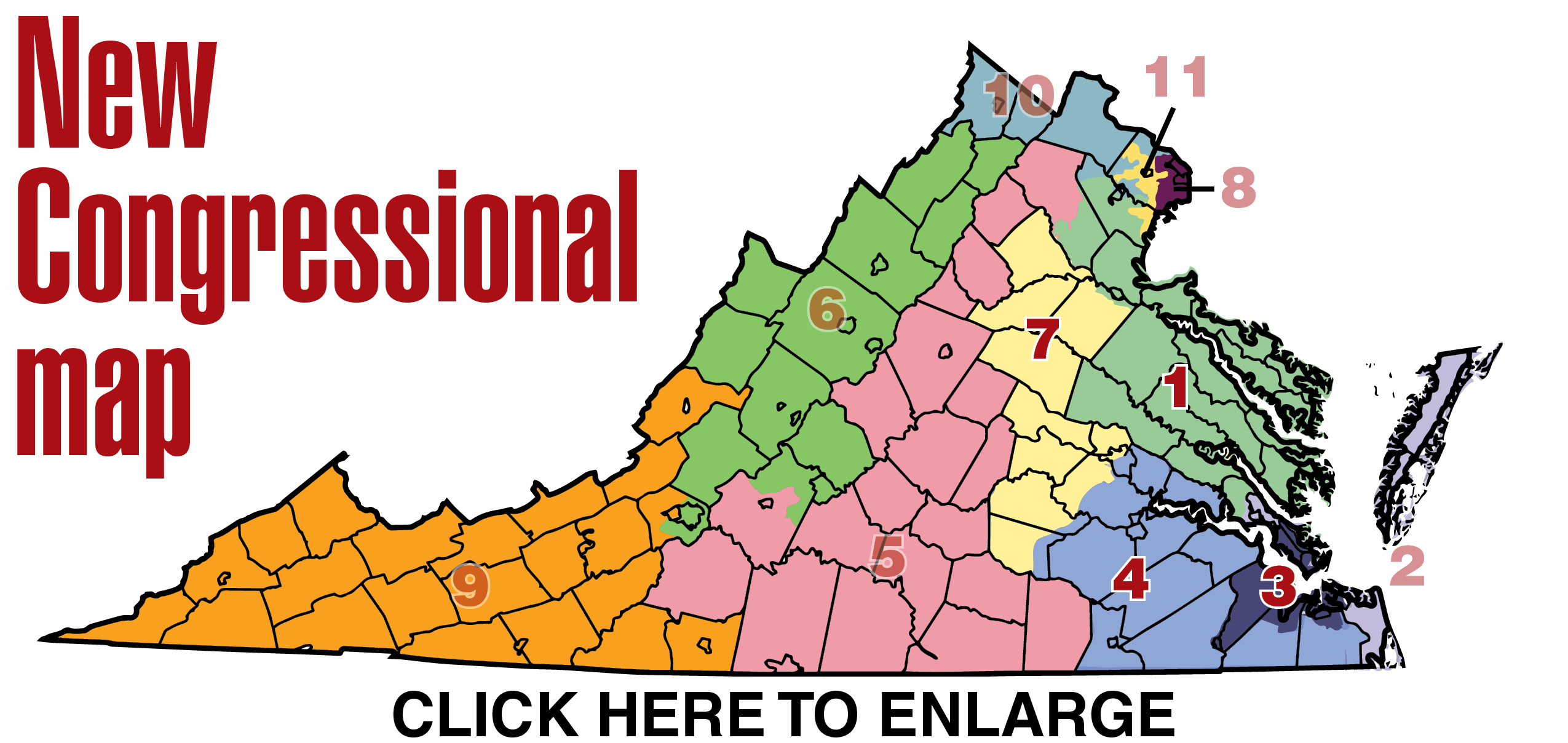

Last May the justices voted unanimously to reject an appeal by three Virginia Republican congressmen — Reps. Randy Forbes-4th District, Dave Brat-7th and Rob Wittman-1st — who objected to the way a federal appeals court had redrawn their district boundaries.

Months earlier, the 4th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals in Richmond imposed a new congressional map after the General Assembly failed to meet a deadline to submit its own plan.

Months earlier, the 4th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals in Richmond imposed a new congressional map after the General Assembly failed to meet a deadline to submit its own plan.

In 2014, U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Virginia had ruled that state lawmakers had packed the 3rd District with African-American voters to diminish their voting power in surrounding districts, violating their equal-protection rights under the Constitution’s 14th Amendment. Rep. Bobby Scott, a Democrat, represents the 3rd District and is the sole African-American in the 11-member Virginia congressional delegation.

During the 2016-2017 term, which begins in October, Supreme Court justices are scheduled to hear an appeal on a second case, Bethune-Hill v. Virginia State Board of Elections, which challenges district maps for the Virginia House of Delegates.

The plaintiffs in that case claim the General Assembly violated the rights of African-American voters in using a racial quota, 55 percent of the voting-age population, to pack voters into a dozen of the state’s 100 House districts. In a 2-to-1 vote, a three-judge federal court panel had ruled that the districts were constitutional and that race had not been the main motivation in creating the House map.

Given the high court’s 2015 ruling in Alabama Black Legislative Caucus v. State of Alabama and this year’s 3rd District case, some local political analysts believe there is a good chance that the court will rule against the General Assembly, forcing state lawmakers to redraw many, if not all, of the districts used to elect the lower house.

“The challenge to the existing lines are likely to prevail in court … The plaintiffs are more likely than not to win,” says Stephen J. Farnsworth, professor and director of the Center for Leadership and Media Studies at the University of Mary Washington.

“Gerrymandering for partisan purposes is constitutionally defended, but what I would call over-gerrymandering for racial purposes, the Supreme Court has ruled against that. My impression is the congressional case and the Bethune-Hill case are being fought on similar grounds,” he says.

“We’ll have to see what the court decides … This could be a case where the line-drawers overplayed their hand, and there will be some modest adjustments” to the state’s election maps, Farnsworth adds.

However, Quentin Kidd, chair of the Department of Government and director of the Wason Center for Public Policy at Christopher Newport University, has some reservations about how the Supreme Court will rule.

“Not being a lawyer or legal expert in any shape or form, in my mind the Supreme Court has twice made rulings that essentially say that you can’t racially gerrymander in a way that is designed to suppress the one-vote-one person power of minority voters. The [Virginia] case is essentially the same argument. In my mind, it has to have some legs in order for the Supreme Court to agree to hear it,” he says.

“But who knows what will happen. The court could come back and say that, in the case of the states, there are different rules that are applied here,” Kidd says.

Democratic swing

The congressional district map imposed by the Fourth Circuit judges radically redrew the 3rd District and the neighboring 4th District. The changes reduced the number of African-American voters in the 3rd while increasing their number in the 4th.

Estimates differ, but the Newport News-based Daily Press reported in May that the federal court’s ruling reduced the number of nonwhite voters in the 3rd District from 60 percent of the voting-age population to fewer than 50 percent, while increasing the nonwhite electorate from 30 to 40 percent in the 4th District.

Along party lines, the difference is even more stark, according to research compiled by the University of Virginia Center for Politics.

Geoffrey Skelley, the center’s media relations coordinator, says voters now living within the borders of the new 4th District voted for President Barack Obama in 2012 by a margin of 61 to 39 percent. Four years ago the old 4th District voted 51-49 for Republican nominee Mitt Romney. While 79 percent of voters in the old 3rd District voted for Obama in the last presidential election, 68 percent of voters living in the new 3rd did so, Skelley says.

That huge swing in Democratic voters persuaded Forbes, the 4th District’s Republican incumbent, to abandon plans to run for re-election although he had held the seat since 2001. He hoped to take over the 2nd District seat of fellow Republican Scott Rigell, who plans to retire in January after six years in office. In the June Republican primary, however, Forbes lost to Delegate Scott Taylor of Virginia Beach.

The candidates vying to succeed Forbes in the 4th District seat are Republican Mike Wade, the sheriff of Henrico County, and Democrat Donald McEachin, an African-American legislator who has represented the Senate’s 9th District — covering Charles City County and parts of Richmond and Henrico and Hanover counties — since 2008.

The Democratic makeup of the redrawn 4th appears to favor McEachin, who says he decided to run for Congress after it became apparent that the courts would uphold the state’s new election map. “There are no parts of my Senate district that are in the old 4th. There are huge portions of my Senate district that are in the new 4th,” he says.

Little change in balance of power

Virginia’s Democrats are encouraged by their prospects of gaining a seat in Congress — the party would have four of 11 seats if McEachin wins. A change in one district, however, won’t mean much on Washington’s Capitol Hill.

“Nationally, Democrats have to pick up 30-plus seats to take back the House [of Representatives], which will be a tall order for them. But I’m sure they’re happy to take a relatively easy one here,” says U.Va.’s Skelley.

If the General Assembly is forced to redraw the boundaries for House of Delegates districts, there probably won’t be much of a change in the balance of power on Richmond’s Capitol Square, either.

“Historically the court tries to adjust the lines as minimally as possible … Favorable court decisions to any challenge to the current lines are likely to change the dynamics of a district here and there, but a wholesale reconfiguration of lines across the state doesn’t seem like a likely outcome even if the plaintiffs win,” says Farnsworth of the University of Mary Washington.

“When you talk about modest changes, you’re likely to have modest impacts, a seat here or there might flip if the plaintiffs win, but the Republican majority is large enough in the House of Delegates to sustain the loss of seats here and there,” he says.

CNU’s political analyst Kidd thinks maybe all 100 of the state’s House of Delegates districts may be changed in some fashion if the plaintiffs in the Bethune-Hill case prevail, but he also predicts little change in the Republican majority in the state legislature.

“It would require an entirely new [election] map,” said Kidd. “You can’t adjust the lines of 12 districts without impacting on the first order, three times that many districts or more … Will it fundamentally change the Republican majority of the House? I’m skeptical of that … The so-called ‘worst-case’ scenario for Republicans is that they do lose seats, but they probably don’t lose their majority.”

List: 50 largest Virginia law firms

t