Dispensing relief

Virginia enters fast-growing medical cannabis oil market

Dispensing relief

Virginia enters fast-growing medical cannabis oil market

After traditional medicine damaged and nearly ruined her liver, Tamara Netzel, tries to manage her multiple sclerosis symptoms with medical cannabis oils and topical creams. Netzel, a retired teacher in Alexandria, has chronic pain and tremors that cause blurred vision. “It calms all that down,” Netzel explains. “It’s not like totally gone. It changes it to a more pleasant feeling.”

Netzel has been using the oils and creams for more than a year. She places medical cannabis oil drops under her tongue each morning and night; sometimes more often depending on what the day is like. Netzel won’t say where she buys cannabis oil because of the legal ambiguities around the products.

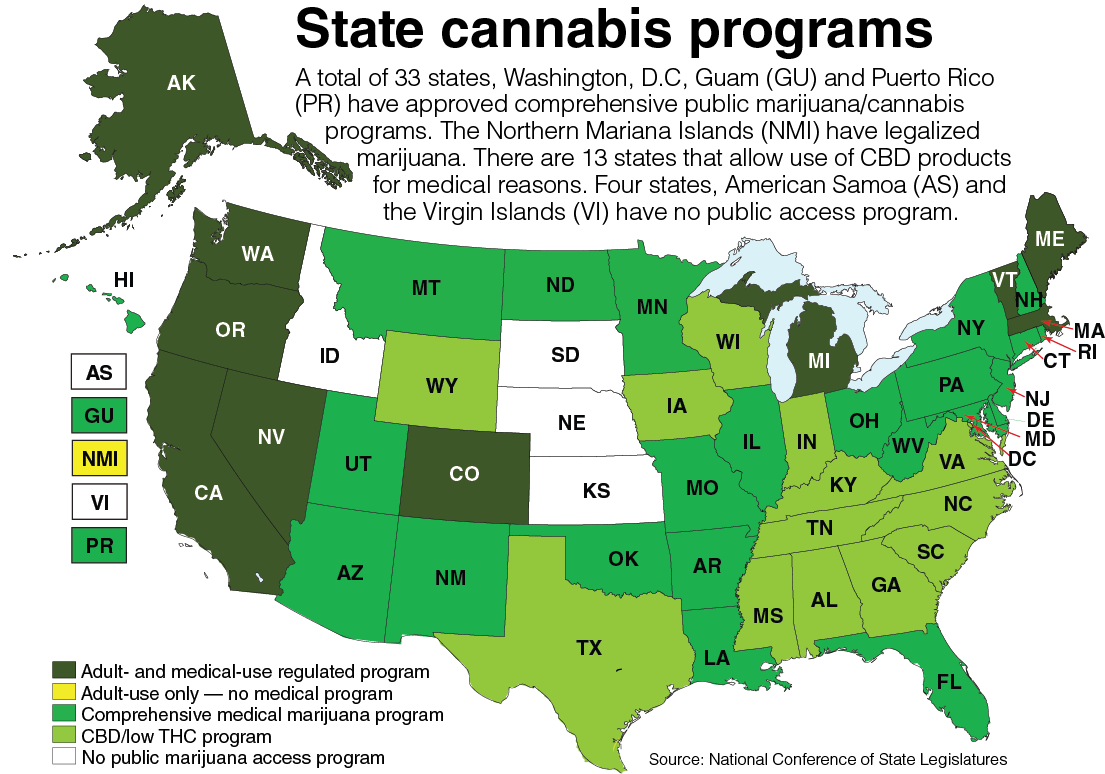

But access to these products is changing in Virginia. Later this year, state-regulated medical cannabis oils are slated to go on sale in the commonwealth. (Incidentally, unregulated products advertised as cannabis oils already are on store shelves in Virginia.)

The state-regulated oils are arriving after a competitive process that saw 51 companies each pay a $10,000 application fee to get the first crack at Virginia’s entry into the fast-growing medical cannabis oil market. The national market is expected to grow 700 percent by 2020 to $2.1 billion, according to The Hemp Business Journal.

The Virginia Board of Pharmacy awarded conditional licenses to five companies to produce and sell the oils. There will be one company operating in each of Virginia’s health service areas, but they’ll be able to sell to patients throughout the commonwealth. The oils will be available to patients who have registered with the state and have a doctor’s written recommendation.

The products are derived from cannabidiol (CBD), a chemical in the part of the cannabis plant that doesn’t produce a high. CBD comes from industrial hemp or marijuana plants and has been used for several conditions, including to mediate side effects of cancer treatment, glaucoma, Tourette syndrome and anorexia due to HIV/AIDs.

State legislators first crafted Virginia’s medical cannabis oil program based on the idea it would serve only patients with severe epilepsy. The parents and families of children suffering from epilepsy spearheaded the charge to expand access to medical cannabis oils in Virginia.

Using international studies and impassioned testimonies, these parents changed the minds of legislators like former Del. David B. Albo, a Republican from Fairfax County. “We all thought it was just another one of these potheads wanting to come here and smoke marijuana,” says Albo, now a partner and lobbyist at the law firm Williams Mullen who worked with one of the failed applicants for Virginia’s cannabis oil licenses.

Persuaded by parents and advocates, Albo and state Sen. David W. Marsden, D-Fairfax, pushed forward the 2015 legislation that created a legal defense for people with severe epilepsy to possess cannabis oils, although the legislation doesn’t legalize medical cannabis oils. Albo says getting the bill passed was like pulling teeth. “It showed people that there are legitimate uses for marijuana,” Albo says. “This is not snake oil.”

In 2018, legislation was passed to expand the use of the medical cannabis oils for any patient — not just ones with intractable epilepsy.

The state-regulated oils may not have more than 5 percent of tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), the chemical in cannabis plants that intoxicates people. There are also limits on the number of cannabis plants each site is allowed to grow and the amount of medical cannabis oil that may be produced. These limits are 12 cannabis plants per patient based on dispensing data from the last 90 days, and no amount of medical cannabis oil that is in excess of what’s needed for their operations.

‘Extraordinarily rigorous’

Nicholas Vita, CEO of New York-based Columbia Care, says Virginia’s application process was “extraordinarily rigorous.” Columbia Care, which operates dispensaries around the country, won the license for the Hampton Roads area. “The detail that the Board of Pharmacy required of applicants and the way in which we had to describe the manufacturing process to assure both safety and quality were among the most thorough we’ve seen anywhere in the United States,” Vita says.

Applicants who did not receive a license say they want more information on why they weren’t picked, and they question whether the Board of Pharmacy had enough expertise to evaluate their plans. In a formal protest by an applicant called CBT, first reported by The Virginian-Pilot, the company accuses the Board of Pharmacy of inappropriate actions in the evaluation process involving a “lack of meaningful review and evaluation” and “failure to use industry experts and subject matter experts.”

In response to these criticisms, Caroline D. Juran, the executive director of the Board of Pharmacy, says the board believes it has been as transparent as it can be under state law. The application process was done as a Request for Application process and involved applications for licensure that are not subject to FOIA, Juran says.

“It should be noted that board staff received several inquiries from potential applicants prior to the application deadline who were seeking assurance from board staff that proprietary information included in a potential application submission would not be released to the public,” Juran says.

Juran says board orders consistent with the board’s decisions will be publicly available within 90 days of Sept. 25, when the board conditionally approved the five licenses.

State Sen. Siobhan S. Dunnavant, R-Henrico, a key legislative figure in developing the state’s medical cannabis program, called the process awkward and uncomfortable so far. “It’s going to need to be modified and refined,” says Dunnavant, an obstetrician and gynecologist. “But I don’t know that we’re far enough along the path to have the full retrospective advantage that we want to have.”

Marsden says no one is happy when they lose and that the Board of Pharmacy did an outstanding job.

Regulatory questions

Beyond the approval process, there are critics of the regulatory framework. Legislators decided on five medical cannabis oil licenses based on the assumption that the oils would serve the needs of severe epilepsy patients. While later legislation expanded the potential pool of patients who can buy the oils in Virginia, the number of licenses for companies selling them stayed the same. “If it was just for intractable epilepsy we probably had too many processing facilities,” Marsden says. “If it’s for any and every condition we probably have too few.”

Gwilt, who also co-founded the Virginia Cannabis Industry Association in 2018, says it likely will take a legislative fix to expand the number of licenses in Virginia but argues the language in the legislation is ambiguous. “One could interpret the language to mean that the board may issue five new permits and renew five permits each year,” she says.

In addition to more licenses, Gwilt wants new types of licenses offered to help meet patient demand and lower the barrier to entry. Right now, state regulations allow only for “vertically integrated” facilities, where the growing, manufacturing and selling of medical cannabis oils is done at one location. Gwilt estimates that development costs for these facilities will range from $5 million to $30 million, depending on each company’s plans.

Gwilt wants to see licenses for companies that want to do only one part of the process, such as growing or selling. “The folks who have the resources to build a fully vertically integrated biopharmaceutical processor are a very select, high-altitude group of individuals,” Gwilt says. “We would like to see broad participation. We would like to see diversity and inclusiveness in the industry.”

Marsden rejects the idea of expanding the kinds of licenses offered for Virginia’s medical cannabis market. It’s the approach Maryland has taken, and Marsden doesn’t think it is working well. “It’s just this complicated arrangement,” he says. “If you’ve got umpteen growers and umpteen processors and 230 distributors, which is like Maryland has, it gets pretty wacky.” Marsden defends the vertically integrated model as being easier to regulate, resulting in fewer fees for the industry.

Five percent cap

Then there are those who feel rules for what’s in the oils themselves need to be less restrictive. Jenn Michelle Pedini, the executive director for the cannabis law reform group Virginia NORML, says the 5 percent cap on THC in the oils means they won’t be helpful to patients with severe conditions like cancer and Parkinson’s.

“The therapeutic potential of these medicines is severely restricted,” says Pedini, who helped craft the 2018 legislation that expanded the use of the oils. She says the 5 percent cap is an arbitrary number that lawmakers were comfortable with rather than a research-based restriction. “We’re framing it in this stigma and trope-fueled perspective, which doesn’t help Virginians,” Pedini says. “Let doctors decide if their patient needs a THC threshold.” She also is a co-founder of the Virginia Cannabis Industry Association.

Dunnavant is drafting a bill to expand the kinds of medical cannabis oil products companies can sell. “Some of the dosing restrictions that were put in the language when we set it up for intractable epilepsy, some of the milligrams per millimeter and some of that other stuff will have to be changed,” she says. Dunnavant declined to share specifics about the bill until it has been finalized.

Marsden says that if the idea is to make the oils more effective for patients without intoxicating them, then he’s fine with changing the THC cap. Additionally, Marsden wants to clarify when pharmacists are required to be present at each location and when they are not.

After years of work on the legislation, Dunnavant and Marsden would like to see the medical cannabis program up and running before making too many more changes. If the Democrats take over the House and Senate in 2019, when every seat in both chambers is up for grabs, there could be an even greater push for marijuana law reforms.

One thing that doesn’t seem likely is going back to the way things were. As Pedini puts it, “The toothpaste is out of the tube.”

a