Creating Hamptonians

Historically black school emphasizes STEM fields and character building

Gary Robertson //November 30, 2015//

Creating Hamptonians

Historically black school emphasizes STEM fields and character building

Gary Robertson //November 30, 2015//

Courtney Edwards, Candace Barnes and Ashanti Bernateau recently were at a table on a long walkway at Hampton University seeking donations for breast cancer research during the school’s homecoming weekend.

But the three seniors — from North Carolina, Guyana and New York City, respectively — weren’t thinking about the upcoming football game; they were thinking about their futures.

All are involved in the sciences at Hampton, and each hopes to go to medical school and also earn a Ph.D. in her field.

They chose the private, co-educational, historically black college of more than 4,500 students largely because of its academic reputation.

Edwards says she grew up around “Hamptonians,” as alumni call themselves, and they were all successful and enthusiastic about the influence the university had on their lives.

“One is a neurosurgeon,” she says of one of her Hamptonian acquaintances, “and that was something I was interested in doing. Seeing their success inspired me to come to Hampton.”

Staying nimble

Hampton is navigating a difficult educational environment, as colleges’ missions, their cost and their value in producing graduates for a changing workforce are being questioned on all sides.

William Harvey, Hampton’s president for 38 years, is an outspoken proponent for keeping his institution nimble in the changing higher-education landscape.

William Harvey, Hampton’s president for 38 years, is an outspoken proponent for keeping his institution nimble in the changing higher-education landscape.

He suggests that the three female students pursuing STEM (science, technology, engineering and mathematics) degrees show how Hampton, traditionally a liberal-arts institution, is adjusting to higher education’s changing, career-focused reality.

“One changes with change or one is inundated with change,” says Harvey. He believes the survival of historically black colleges and universities (HBCUs) and many other schools will depend upon the quality of their academic programs.

Harvey, the owner of a Pepsi-Cola bottling company in Michigan, has been putting his own money into Hampton’s educational programs — $2 million so far — to provide student scholarships and to help raise wages and salaries.

The 74-year-old president, who earned his doctorate in college administration from Harvard University, believes that a university needs to be run like a business. He says that business-like approach means constantly innovating, monitoring programs and expenses and making bold moves when they are appropriate.

Bold moves

One example of Hampton University’s bold moves is the $225 million Proton Therapy Institute for the treatment of cancer. The 98,000-square-foot facility is touted as the largest of its kind in the world. Seventeen proton centers now operate in the U.S. and a dozen more are under construction.

Proton therapy is designed to target and kill tumors while sparing surrounding healthy tissue. The center can treat about 1,500 patients a year.

Since its inception five years ago, the institute’s growth has been slower than originally expected, but the university remains bullish about its prospects. The Daily Press in Newport News reported that by September the center had treated a total of 1,274 patients since 2010. Hampton University officials, however, say that number does not fully reflect the level of activity at the institute because patients receive multiple treatments. Patients typically undergo 38 to 42 treatments, and the center serves up to 50 patients daily, says B. Da’Vida Plummer, the university’s assistant vice president for marketing and media.

In another venture, Harvey recently used university funds to acquire the tallest building in Hampton, a 14-story, tenant-occupied structure. He plans to erect an antenna on the building that will gather weather-related information from satellites and then employ scientists to analyze the “big data” for the Hampton Roads area. “We dream no small dreams here,” Harvey says.

Hampton already works with NASA on three satellite-related programs, and a fourth is set to begin in June. The biggest focus of the satellite missions has been the study of “night-shining” clouds, iridescent polar clouds that form 50 miles above the earth’s surface that are part of high-altitude weather patterns.

Harvey says reaching outside the traditional boundaries under which many universities operate is one way that Hampton distinguishes itself in a competitive market.

He also says this is how the university helps boost the economy throughout the region, in addition to student and faculty spending and the school’s purchase of local goods and services. Last year, the university had operating expenses of $150 million.

Recruiting Hispanics

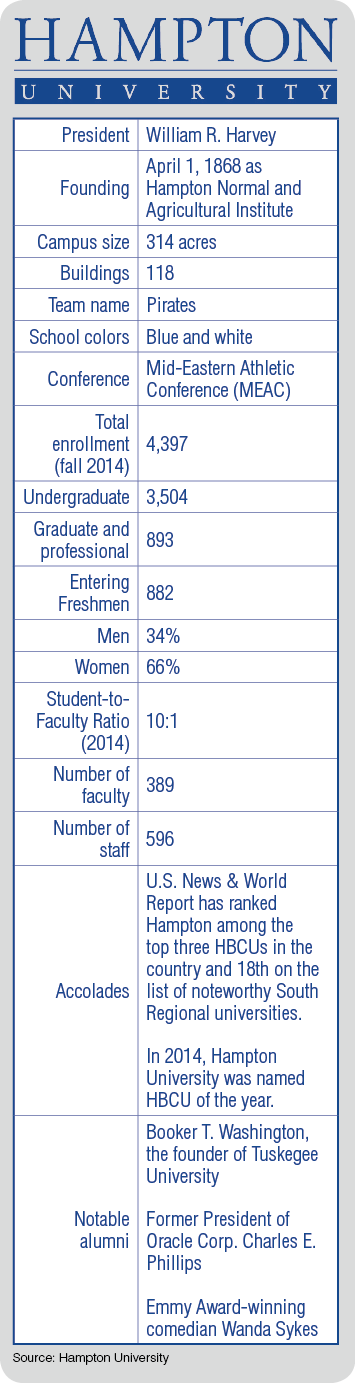

Hampton University sits on 314 acres near the mouth of the Chesapeake Bay and tells prospective students that it will be their “Home by the Sea.”

It was founded in 1868 by Gen. Samuel Chapman Armstrong, superintendent of the Freedmen’s Bureau of Virginia after the Civil War. Armstrong later pioneered education in the U.S. for Native Americans, many of whom were taught at Hampton until 1923.

Harvey employs one of Armstrong’s quotes constantly. “I want everything at my institution to excel, and I do not know why it cannot,” the Hampton president says.

Drawing from Armstrong’s efforts to educate newly freed slaves and American Indians, Harvey recently launched an initiative to reach out to Hampton Roads’ Hispanic population. “I believe in equal opportunity,” Harvey says, “and there’s a crying need for involving Hispanics in our country in higher education.”

Hampton is opening its first initiative for Hispanic education in Newport News.

Changes in financial aid

In its disclosure statement, the university cited several factors that led to the decline, including the university’s desire to reach its targeted enrollment of 5,000.

But other factors also contributed to a bigger drop than anticipated. They included a weak national economy, flat funding from federal sources and no significant increases in the federal Pell Grant program for needy students, according to the statement.

Still, Hampton also had lowered its student-faculty ratio from 12-to-1 to 10-to-1.

Martin Miles, Hampton’s director of financial aid and scholarships, says one of the biggest changes affecting HBCUs such as Hampton in recent years was the curtailment of loans made to students’ parents or guardians under the PLUS loan program.

The stricter rules now apply to the “adverse credit history” of prospective borrowers, “Enrollments dropped precipitously at many HBCUs,” Miles says, because students couldn’t raise the money to attend college.

But Miles says that Hampton did better than most HBCUs at attracting and retaining students because of the scholarship help it provides from its own resources. Hampton has one of the largest endowments among all HBCUs, $288 million. “Last year, Hampton provided $21.4 million in scholarships for 1,914 students,” Miles says.

Recent changes in the language of the PLUS loan program have improved the situation and enabled more students to obtain loans, Miles adds. In August, Hampton welcomed a freshman class of 1,053, an increase of 150 students from the previous year.

Emphasis on STEM fields

Barbara Inman, Hampton’s vice president of administrative services, says the growth in STEM disciplines and research initiatives has contributed to the increased enrollment.

Harvey pushed hard for more STEM funding for HBCUs at a White House conference in September. In early October, he asked Silicon Valley technology leaders to help fund an Innovation Center at Hampton that would have an emphasis on STEM disciplines. “Silicon Valley has a dismal record in hiring minorities,” Harvey says.

Providing a STEM-focused Innovation Center at Hampton would help level the playing field for minorities in the high-tech industry, he believes. “I reminded the people in Silicon Valley that we are a national institution. Last year we had 110 kids from California in the freshman class,” Harvey says.

Overall, Hampton has students from 49 states and 35 territories or other countries.

Building character

Hampton brands itself as an institution where a student’s character is just as important as his or her classroom performance.

JoAnn Haysbert, Hampton’s executive vice president and provost, is a stickler on the subject. “Hampton University builds leaders with character because of its standard of excellence. When parents send their children to Hampton, they know what they’re getting,” Haysbert says. “Our freshmen don’t have cars, they have curfews.”

She says that, as students learn more about the responsibilities of independence, they earn the right to have more independence.

Haysbert was president of an HBCU in Oklahoma for seven years before returning to Hampton, which she had first joined in 1980.

She says that a lot of the loose living and misbehavior she’s seen on other college campuses have no opportunity to blossom in Hampton’s close-knit campus community. “Where else in 2015 would you find a curfew?” she asks rhetorically. “Men can’t wear hats in class. Graduations are dignified, no beer-popping, no hands waving.

“We don’t apologize for who we are,” Haysbert adds. “It’s known, it’s expected.”

The university’s “out-by-5” policy stipulates that students who wantonly violate the school’s code of conduct or destroy property are sent home by the close of the day. “You’re out by 5,” Haysbert says.

Justin Shaifer, a senior and president of the Student Government Association, is from the South Side of Chicago. He grew up in a single-parent home in a neighborhood teeming with gangs.

He says that arriving at Hampton, with its stiff requirements for academics and good behavior, was a culture shock. He hated the curfew, but in reflection he says it kept him focused on his schoolwork and instilled discipline.

“I was a little goofy in high school,” Shaifer says. “It took me awhile, but I realized I had been slacking all those years. I had let other people become my excuses.”

Shaifer, who is studying marine environmental science, hopes to become an attorney with a focus on environmental law. Before coming to Hampton, he says, such a goal would have never entered his mind. “I had a very narrow view of the capabilities of my own people,” he says. “But here, everyone is hustling. You feel out of place if you’re not.”

Not done yet

Back in the president’s office, Harvey says his work at Hampton University is not done, because the institution has to evolve further to stay successful.

Twenty-seven buildings have been erected during Harvey’s tenure, more than 70 academic programs have been added, and the endowment has grown tenfold. In addition, the university has become more diverse. “We’re about 10 percent white, and I like that,” Harvey says.

Hampton recently added men’s lacrosse as a varsity sport as well as women’s soccer, believing the two sports will attract high-caliber student athletes of all races from all areas of the country.

“HBCUs have had a glorious history in this country of dealing with the underprivileged, the undereducated and first-generation college students. But we can’t move into the future with just those three categories,” Harvey says, citing a need for increased recruitment of students from diverse backgrounds.

To keep its enrollment up and its options open, Harvey says, Hampton will be doubling down on what has made it successful: strong teaching, interesting research and public service.

When changes are needed, Harvey says, he won’t hesitate to make them. At this stage life, at his age, Harvey states, he doesn't say anything he doesn't mean.

l