The Roanoke and New River valleys are developing a potent mix.

While organizations such as Virginia’s Blue Ridge and Roanoke Outside promote the region’s manmade attractions and natural wonders, the valleys are building their local economies on technology, medical research, education and entrepreneurship.

The outdoor and vacation promotional efforts already are attracting attention to the region. The area’s trails, rivers, breweries, wineries and music venues have been featured in Southern Living, Men’s Journal, USA Today, CraftBeer.com, Expedia and most recently, Outside Magazine.

The rivers, the Appalachian Trail and the Blue Ridge Parkway are natural draws, and the annual Blue Ridge Marathon pulls in runners attracted by the challenge of the country’s toughest road race.

But Catherine Fox, vice president of public affairs and destination development at Virginia’s Blue Ridge, says the region is claiming a new title. “We’re putting our stamp on Virginia’s Blue Ridge as America’s East Coast Mountain Biking Capital,” she says.

But Catherine Fox, vice president of public affairs and destination development at Virginia’s Blue Ridge, says the region is claiming a new title. “We’re putting our stamp on Virginia’s Blue Ridge as America’s East Coast Mountain Biking Capital,” she says.

That may sound like hype, but in May, the International Mountain Bicycling Association (IMBA) designated the region and its more than 300 miles of trails a Silver-Level IMBA Ride Center. It is the only silver-level destination in Virginia and one of just 15 in the world. Other regions on the list include Steamboat Springs and Vail Valley, Colo.; Sun Valley, Idaho; Santa Fe, N.M.; and Jackson Hole, Wyo.

“We’re just ecstatic to be silver level and to be in such elite company,” Fox says. “When you add the Greenways [trail system] to it, you really are appealing to a wider audience than just that of the mountain biker, but people who love to bike.”

Fox expects many of those people to participate in the first Grand Fondo, which will take cyclists over 30-, 50- and 100-mile road courses through Botetourt County this October. She’s also excited about the potential to connect downtown Roanoke to the trails at Explore Park, which is just off the Blue Ridge Parkway.

Montgomery County’s supervisors and Christiansburg’s Town Council talked in June about eventually extending the Huckleberry Trail, which connects Blacksburg and Christiansburg to Roanoke County and the Roanoke Valley Greenway.

Research center expansion

The valleys already are connected by institutions, perhaps most notably the Virginia Tech Carilion School of Medicine and Research Institute in Roanoke.

Created by Tech and Carilion Clinic, the region’s largest employer, the medical school became the university’s ninth college in July. Meanwhile, the research institute is working on a new building to accommodate 25 to 30 new research teams — about 350 people.

“It’ll be an interesting impact on the demographic and the age distribution of the population in the area,” says Michael Friedlander, the institute’s founding executive director. “It brings a lot of culture and diversity to the city, which I think is good.”

“It’ll be an interesting impact on the demographic and the age distribution of the population in the area,” says Michael Friedlander, the institute’s founding executive director. “It brings a lot of culture and diversity to the city, which I think is good.”

The research center already is “a major nationally recognized and internationally recognized epicenter of modern biomedical research. … It gives us — the city of Roanoke and the valley and the region — a national identity and brand,” Friedlander says.

The institute also gives the region’s economy a significant boost. With more than 200 employees earning an average salary of about $80,000 (in addition to about 100 students), the facility spends $25 million or more in grant money each year. “That is new money” that flows in from outside the region, Friedlander says.

Since its research teams began working in 2010, the institute has had a regional economic impact of about $400 million, Friedlander says. Its influence, however, is more than economic.

Researchers Sharon Ramey and Stephanie DeLuca, for example, developed a therapy that trains the brains of children with cerebral palsy to recover function. Ramey spent three weeks in Hue, Vietnam, this past spring teaching others about the therapy.

“This therapy was invented and developed by our folks … for kids, and now it’s being used worldwide, and our folks are training other people how to use it,” Friedlander says.

Institute researchers also have created six companies.

Robert Gourdie, for example, has developed a treatment to help heal foot ulcers in patients with diabetes.

That research led Gourdie and a former postdoctoral fellow, Gautam Ghatnekar, to found FirstString Research Inc. in 2005. Last year the company received the Small Business Administration’s Tibbetts Award for innovation in a White House ceremony.

Another researcher-entrepreneur is Warren Bickel. His research on how to reduce cravings among people with addictions led to the creation of BEAM Diagnostics.

The company now is part of the second cohort at RAMP, the Regional Acceleration and Mentorship Program, in downtown Roanoke.

RAMP program

Housed in a former hospital building, RAMP is a cooperative venture involving the city, Virginia Western Community College and the Roanoke-Blacksburg Technology Council (RBTC).

RAMP businesses get a place to work and internet access for a little more than 11 months, says Robert McAden, RBTC’s president and CEO. They also receive a five-to-six-month educational program and mentoring.

RAMP businesses get a place to work and internet access for a little more than 11 months, says Robert McAden, RBTC’s president and CEO. They also receive a five-to-six-month educational program and mentoring.

RAMP is not a business incubator, McAden says. “It’s really much more of a focused program … after the program ends, you don’t get to just stay here. You have to go make it on your own.” The program ends with a demo day during which businesses pitch themselves to potential investors.

Every business gets the same educational component, but the mentoring is specialized to each company. The companies also help each other.

“I would say they learn as much from each other going through this and sharing the shared experience of what it’s like to be an entrepreneur and what it’s like to go through this,” McAden says. “We’ve had a good mix of software and medical and engineering, so they kind of run the gamut as far as what the companies do, but they have to have some type of technology component to be considered.

“The other thing is we have to feel like they are a company that we feel like we can help through the mentors we have in this region and through the educational component,” he adds. “We want to feel they are coachable and are open to suggestions and open to the opportunities that are provided here.”

Figuring out how to turn research into businesses is vital to the region’s future, McAden says. “I think RAMP is just one facet of that, of helping researchers and helping the community look to the research and look to that intellectual property and how do we commercialize it and how do we use that to really propel the growth of this region.”

Workforce development

Another important facet in economic growth is the creation of a trained workforce. Montgomery County Public Schools are helping students learn about the vocational opportunities that await them after high school.

“My personal opinion is that a student doesn’t understand what it’s like to work until they do it, and we’d like for them to understand it before they leave high school,” says Rick Weaver, the county’s supervisor for career and technical education.

“My personal opinion is that a student doesn’t understand what it’s like to work until they do it, and we’d like for them to understand it before they leave high school,” says Rick Weaver, the county’s supervisor for career and technical education.

The schools — and the Montgomery County Chamber of Commerce, which is supporting the program — also want students to know what kind of jobs the region offers.

About 400 county students got work experiences during the 2017-2018 academic year. Many of them worked at fast-food restaurants, but others worked for an electrical contractor, an HVAC contractor, a timber-frame contractor, a veterinary clinic and a dairy.

Students also worked at the school system — in classrooms, the bus garage, cafeterias and IT desks. They also served as school custodians and, in one case, as a marketing coordinator for high-school athletics.

“We’re trying to have our kids well informed about the work world, about the options in the work world,” Weaver says. “And we’re trying to raise the visibility of students who are already doing something other than going to a four-year college, and getting there and saying, ‘I’m here. Now what do I do?’”

Students who complete work programs and pass a work readiness exam get a special seal on their diplomas. Graduates who head straight into the workforce, the military or technical training participate in a ceremony modeled on the letter-of-intent signings schools stage for star athletes who get college athletic scholarships. About 60 students took part in the first ceremony, held in May.

“For years, society in general and parents specifically have been convinced that we all have to go to college, and schools have been celebrating who’s going to college,” Weaver says. “Well, there’s other paths, and we’re trying to make that clear to everyone.”

But Catherine Fox, vice president of public affairs and destination development at Virginia’s Blue Ridge, says the region is claiming a new title. “We’re putting our stamp on Virginia’s Blue Ridge as America’s East Coast Mountain Biking Capital,” she says.

But Catherine Fox, vice president of public affairs and destination development at Virginia’s Blue Ridge, says the region is claiming a new title. “We’re putting our stamp on Virginia’s Blue Ridge as America’s East Coast Mountain Biking Capital,” she says. “It’ll be an interesting impact on the demographic and the age distribution of the population in the area,” says Michael Friedlander, the institute’s founding executive director. “It brings a lot of culture and diversity to the city, which I think is good.”

“It’ll be an interesting impact on the demographic and the age distribution of the population in the area,” says Michael Friedlander, the institute’s founding executive director. “It brings a lot of culture and diversity to the city, which I think is good.” RAMP businesses get a place to work and internet access for a little more than 11 months, says Robert McAden, RBTC’s president and CEO. They also receive a five-to-six-month educational program and mentoring.

RAMP businesses get a place to work and internet access for a little more than 11 months, says Robert McAden, RBTC’s president and CEO. They also receive a five-to-six-month educational program and mentoring. “My personal opinion is that a student doesn’t understand what it’s like to work until they do it, and we’d like for them to understand it before they leave high school,” says Rick Weaver, the county’s supervisor for career and technical education.

“My personal opinion is that a student doesn’t understand what it’s like to work until they do it, and we’d like for them to understand it before they leave high school,” says Rick Weaver, the county’s supervisor for career and technical education. Other robotic farming projects are much more directly aimed at commercialization. Mahindra Group, for instance, established the Mahindra AgTech Center at Virginia Tech in the Virginia Tech Corporate Research Center in Blacksburg. Mahindra, a $19 billion federation of companies based in India, has more than 200,000 employees in 100 countries. While Mahindra’s business interests range from aerospace to financial services, it sells more tractors than any other company in the world. The first project of Mahindra AgTech Center is to develop a robotic table grape harvester that can be mounted on those tractors.

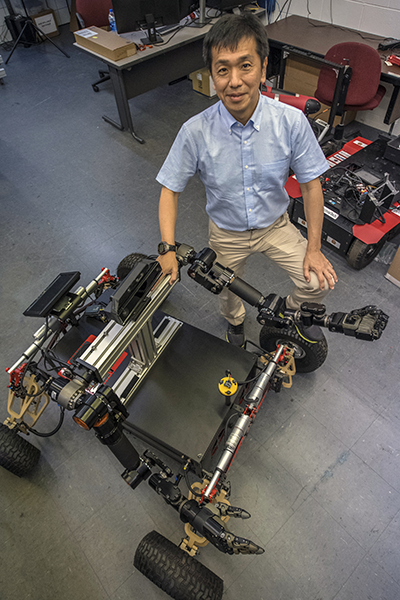

Other robotic farming projects are much more directly aimed at commercialization. Mahindra Group, for instance, established the Mahindra AgTech Center at Virginia Tech in the Virginia Tech Corporate Research Center in Blacksburg. Mahindra, a $19 billion federation of companies based in India, has more than 200,000 employees in 100 countries. While Mahindra’s business interests range from aerospace to financial services, it sells more tractors than any other company in the world. The first project of Mahindra AgTech Center is to develop a robotic table grape harvester that can be mounted on those tractors.