If insurance brokers seem to have a bounce in their step these days, it might be that they’re feeling very much in demand.

For the next few months, anyone who can help small businesses and individuals with the task of picking health insurance is going to be pretty popular.

Choosing coverage in the individual and small-group markets is never easy, but this year it is especially complicated. For one thing, starting in January the Affordable Care Act will require more businesses to offer insurance coverage to their employees. The threshold for 2015 is 100 or more full-time equivalent (FTE) employees, but next year the employer coverage mandate will include any business with 50 FTEs.

Planning for 2016 is a new challenge for insurers, too — the policies they wrote last year for 2015 were based on guestimates of what kind of claims they would have to pay. This year’s proposed policies for 2016 are based on a year of actual experience. So that means that their premiums and underwriting rules are changing a lot.

“It’s such a complicated decision that we’re finding that employers are really leaning on us to help them,” says David Blanchard, principal with Digital Benefit Advisors in Richmond.

“It’s such a complicated decision that we’re finding that employers are really leaning on us to help them,” says David Blanchard, principal with Digital Benefit Advisors in Richmond.

Insurance carriers are farther along in figuring out what next year will bring. They submitted their proposed premiums to the State Corporation Commission’s Bureau of Insurance (BOI) back in April. The ACA rules require insurers proposing plans with rate increases of 10 percent or more to present those plans for a public rate review. Nineteen plans from 10 insurers met that requirement. Overall, the proposed rate increases in Virginia are lower than in many states, where increases above 20 percent are common.

Enrollment begins Nov. 1

The selection process for businesses and individuals begins with the start of the open enrollment period, which runs from Nov. 1 of this year through Jan. 31, 2016. In late August, the BOI submitted its recommendations to the federal Department of Health and Human Services. The approved rates won’t be available until the fall, in time for the open enrollment period.

In July, the BOI asked insurers to present details of their most popular plans based on statewide enrollment, as well as rate details on plans with average, minimum and maximum rate changes. It’s not yet clear how many Virginia plans will be offered by carriers participating in the federal exchange (HealthCare.gov), but last year there were 172, with 90 individual plans and 82 small-group plans, says Ken Schrad, spokesman for the State Corporation Commission.

Even with the public presentations and other details available online, it’s nearly impossible to make comparisons. There are different levels of federal subsidies, plus local trends in health costs, morbidity and tobacco use to consider.

Plans also can change significantly from one year to the next, with no immediate clues to help consumers figure out why. One of Aetna’s small-group plans, for example, showed a proposed maximum premium increase of 64 percent for 2016 over 2015. Seems outrageous, right? When asked, Aetna explained that much of that increase is based on the fact that the plan is changing from a bronze-level plan on the ACA exchange to a silver-level plan for 2016, which would offer better coverage.

What’s also true is that insurers and health-care providers come to the market in a variety of ways. Aetna, for example, has four different companies offering small-group business insurance for next year. Its Innovation Health Plan and Innovation Health Insurance Company are joint ventures with Inova Health System in Northern Virginia. Then there’s Aetna Health, which offers health-maintenance organization (HMO) plans across the state, and Aetna Life Insurance, which offers preferred-provider organizations (PPOs).

Plus, not all plans are available in all areas, and even plans that are offered statewide are priced differently depending on location and other factors. Anthem’s popular Healthkeepers plan, for example, has just a 4.8 percent premium increase for 2016 for all ages of enrollees. But while a 25-year-old in Richmond would pay $217 a month for a silver-level plan, he or she would face a higher price in almost any other part of the commonwealth.

Even the available data about average increases proposed for an insurance plan aren’t particularly helpful, Blanchard says. “While the general average [rate increase] from Anthem or some other insurer might be 8 percent or 13 percent, that doesn’t mean some client doesn’t get a decrease, or that they won’t get an increase of 80 percent,” he says. There are simply too many variables and options.

Blanchard also notes there are new reporting requirements for employers to learn, such as how to count your employees to determine what the law requires. “In many ways, the [50- to 99-employee] market segment is the most complicated segment for insurance right now across the country,” he says. “There’s significant pressure on the pricing as well as pressure on the coverage.”

Regulatory pressure

There is pressure on regulators, too. Back in July, as state-level regulators like the Bureau of Insurance were reviewing the proposed rate increases, the federal Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) sent a letter urging them to keep premiums affordable. The letter, from Kevin Counihan, director of the CMS Center for Consumer Information and Insurance Oversight, pointed to data showing that more recent enrollees are healthier and thus making fewer claims.

The letter also said there has been a recent decline in the “pent-up demand for services” that produced more claims in the ACA’s first few years, as previously uninsured people got coverage and started to use it. In addition, Counihan said that recent medical costs were showing “moderate” cost increases. “Because recent trend experience can often provide a useful guide to the near future, these data may be relevant when evaluating the reasonableness of trend assumptions for 2016,” he wrote.

When Virginia’s BOI held its public review session the day after Counihan’s letter was released, insurance commissioner Jacqueline Cunningham made clear at the start of that three-hour meeting that the rules by which the premium increases would be measured were already set.

“You can’t disapprove a rate just because you do not like it, is that correct?” she asked David Shea, the BOI actuary. Shea said yes. “As long as the data and the assumptions are actuarially supportable and justifiable, then Virginia will approve the rate,” he said.

The new rates, though, aren’t necessarily the only option on the exchange. Carriers also are offering to let customers renew policies under the existing 2015 rates, Blanchard says. So that option is at least more specific than the 2016 options, which won’t be known until the rate-approval process is completed this fall. “We’re starting conversations [with clients] now, but they’re not substantive … because we don’t have all the options,” he says.

Consumers can see some details of what carriers are proposing at a website run by the CMS, ratereview.healthcare.gov. Insurers who are proposing rate increases at 10 percent or higher must go through a public rate review, and the website has some details and explanations for the increases. The explanations, though, generally don’t bring the clarity that individuals or businesses want.

The reasons given for a rate increase vary, but they often cite the increase in health-care services, or a rise in the medical claims made. Doug Gray, executive director of the Virginia Association of Health Plans, says consumers and business owners should take some comfort, because Virginia’s insurance marketplace has rate increases being proposed that are lower than many other states. “Our market is relatively stable, and we have more [providers] competing in our market than in some of the others. And frankly that’s what it’s supposed to do.”

Today Don Shockey is chairman of the board of the Shockey Companies, which has three businesses – Howard Shockey & Sons, the original company, which is a construction firm; Shockey Precast, a concrete manufacturer; and Shockey Properties, a commercial real estate firm with more than 4 million square feet either owned or under management. Shockey Companies’ revenues last year rose to $117 million, up from $105 million in 2014.

Today Don Shockey is chairman of the board of the Shockey Companies, which has three businesses – Howard Shockey & Sons, the original company, which is a construction firm; Shockey Precast, a concrete manufacturer; and Shockey Properties, a commercial real estate firm with more than 4 million square feet either owned or under management. Shockey Companies’ revenues last year rose to $117 million, up from $105 million in 2014.

There are a few reasons salaries went down during the toughest years after the recession, says Janet Hutchinson, associate dean for career development at the University of Richmond School of Law. “The employers that were the most impacted were the large law firms that paid the highest starting salaries, [and] at the height of the downturn some of those employers had to rescind offers,” she says. “After that, they started hiring a smaller number of graduates, and they haven’t returned to hiring the same number.”

There are a few reasons salaries went down during the toughest years after the recession, says Janet Hutchinson, associate dean for career development at the University of Richmond School of Law. “The employers that were the most impacted were the large law firms that paid the highest starting salaries, [and] at the height of the downturn some of those employers had to rescind offers,” she says. “After that, they started hiring a smaller number of graduates, and they haven’t returned to hiring the same number.” Sorenson was acknowledging a trend well underway in many urban markets as suburban office parks empty out in favor of major transit corridors. But his comments “sent shock waves around the country” because it showed even giant companies were feeling competitive pressures to get and keep the best workers, says John Martin, CEO of Southeastern Institute of Research, a Richmond-based firm with a background in community planning and transportation. “We’ve reached a tipping point in moving to a multimodal society.”

Sorenson was acknowledging a trend well underway in many urban markets as suburban office parks empty out in favor of major transit corridors. But his comments “sent shock waves around the country” because it showed even giant companies were feeling competitive pressures to get and keep the best workers, says John Martin, CEO of Southeastern Institute of Research, a Richmond-based firm with a background in community planning and transportation. “We’ve reached a tipping point in moving to a multimodal society.” The Broad Street corridor was chosen for the Pulse system because it has the “highest existing and projected population and employment densities and the most transit supportive land use in the Richmond region,” according to RVA Rapid Transit, an organization that would like one day to see four BRT lines reaching into surrounding counties and intersecting in downtown Richmond. Within a half-mile of the planned BRT line, there are 33,000 people and 77,000 jobs with the potential for more, the group says.

The Broad Street corridor was chosen for the Pulse system because it has the “highest existing and projected population and employment densities and the most transit supportive land use in the Richmond region,” according to RVA Rapid Transit, an organization that would like one day to see four BRT lines reaching into surrounding counties and intersecting in downtown Richmond. Within a half-mile of the planned BRT line, there are 33,000 people and 77,000 jobs with the potential for more, the group says. Christopher Bailey, VHHA executive vice president, says all the major health systems in the commonwealth eventually will be subscribing to VHI’s service. “It just takes time,” he says.

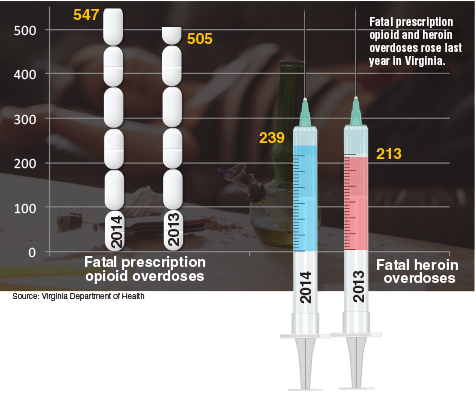

Christopher Bailey, VHHA executive vice president, says all the major health systems in the commonwealth eventually will be subscribing to VHI’s service. “It just takes time,” he says. An opioid overdose often comes on quickly, and by the time emergency care arrives it can be too late. “The goal was: How do you bridge that gap and keep a patient breathing until the ambulance arrives? That was the value proposition” behind creating Evzio, Edwards says.

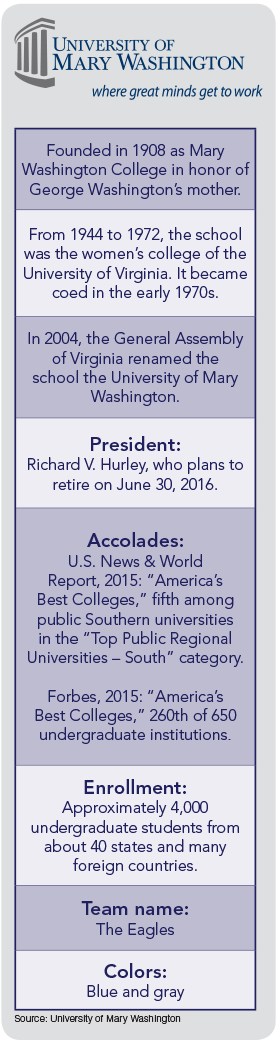

An opioid overdose often comes on quickly, and by the time emergency care arrives it can be too late. “The goal was: How do you bridge that gap and keep a patient breathing until the ambulance arrives? That was the value proposition” behind creating Evzio, Edwards says. Plus, the university hosts the region’s economic development programs. In 2011 UMW launched a partnership with the FRA and formed the University Center for Economic Development. UMW President Richard Hurley has been pushing the school to take a lead role, saying the region “is ripe with opportunity to further develop economically, and I would like to see UMW become a key player in that effort.”

Plus, the university hosts the region’s economic development programs. In 2011 UMW launched a partnership with the FRA and formed the University Center for Economic Development. UMW President Richard Hurley has been pushing the school to take a lead role, saying the region “is ripe with opportunity to further develop economically, and I would like to see UMW become a key player in that effort.” Part of the reason why a local research effort might produce better results is that it will take some legwork to get details on these commuters. Tim Schilling, a UMW economics professor who is leading the research center, says the Fredericksburg region is divided between multiple metropolitan statistical areas, or MSAs. “When you look at nationally collected data like that you kind of have to sort through it and do the best you can,” he says.

Part of the reason why a local research effort might produce better results is that it will take some legwork to get details on these commuters. Tim Schilling, a UMW economics professor who is leading the research center, says the Fredericksburg region is divided between multiple metropolitan statistical areas, or MSAs. “When you look at nationally collected data like that you kind of have to sort through it and do the best you can,” he says. The university also has its Stafford Campus located in Stafford County a few miles west of Interstate 95. Opened in 1999, with a second 40,000-square-foot building constructed in 2007, it offers academic degrees and professional development programs for midcareer professionals.

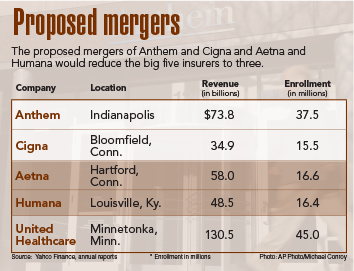

The university also has its Stafford Campus located in Stafford County a few miles west of Interstate 95. Opened in 1999, with a second 40,000-square-foot building constructed in 2007, it offers academic degrees and professional development programs for midcareer professionals. Beyond the usual upbeat press statements, the companies involved in these mergers are offering few details about how the deals will affect the market. Anthem launched a website (betterhealthcaretogether.com), telling employers and individual customers that the combined company “will expand access to an unmatched network of hospitals, physicians, and health-care professionals. No company will be better positioned to deal with the challenges of a fast-changing health-care market,” the company says.

Beyond the usual upbeat press statements, the companies involved in these mergers are offering few details about how the deals will affect the market. Anthem launched a website (betterhealthcaretogether.com), telling employers and individual customers that the combined company “will expand access to an unmatched network of hospitals, physicians, and health-care professionals. No company will be better positioned to deal with the challenges of a fast-changing health-care market,” the company says. “It’s such a complicated decision that we’re finding that employers are really leaning on us to help them,” says David Blanchard, principal with Digital Benefit Advisors in Richmond.

“It’s such a complicated decision that we’re finding that employers are really leaning on us to help them,” says David Blanchard, principal with Digital Benefit Advisors in Richmond.