The people who will benefit most from a new Medicaid initiative in Virginia also are the ones who need the most help and cost the most to treat.

On Aug.1, a program called Commonwealth Coordinated Care Plus (CCC Plus) was launched by the Virginia Department of Medical Assistance Services (DMAS). CCC Plus started in Hampton Roads and will be expanded across the rest of the commonwealth by the end of the year.

About 216,000 people in Virginia will be enrolled in the program when it is fully in place. Many are “dual-eligible” enrollees who get benefits from Medicaid and Medicare. Many are older adults or people with disabilities. They often receive a lot of services and medical care without anyone coordinating their treatment. Sometimes there is unnecessary care, which doesn’t help the patient or the state’s Medicaid budget.

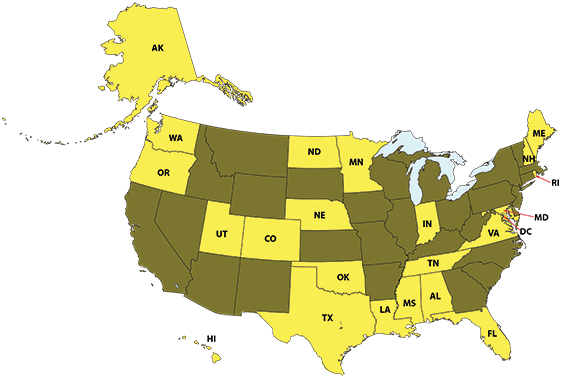

CCC Plus has been in development for several years in Virginia, and other versions of the program are already in place in about 30 states. The program is making its debut in Virginia after years of steady criticism of the overall Medicaid system from conservatives who call it wasteful and ineffective. Recent failed efforts by Congress and the White House to end the Affordable Care Act included major funding cuts to Medicaid spending.

CCC Plus is designed to make services for this particular population more effective and less wasteful. The elderly and people with disabilities represent 23 percent of Virginia’s Medicaid population, yet they consume 68 percent of the state’s $8.41 billion Medicaid budget. These figures are from 2016.

“How do you bend the cost curve?” asks Cindi B. Jones, the director of DMAS. “It’s not an easy thing to do. We feel that by focusing on quality, the savings will come.”

Managed-care system

The program moves the elderly and disabled patients from a fee-for-service system to managed care, which gives insurers tighter control over medical spending. These patients are eligible for a lot of services, but they don’t always know the best way to access or use them.

“There’s nobody trying to coordinate their care” except for the patients themselves or a support person, usually a family member, Jones says. “I call those ‘fend for yourself’ programs. Sometimes that process is almost worse than the disease.”

Before CCC Plus was launched, a test program in Virginia limited to about 30,000 people began in 2014. It showed good results, Jones says. Patients liked having care coordinators, and the program cut the costs associated with those patients, she says.

Virginia-based Optima Health has the contract with DMAS to handle services to eligible recipients in the Hampton Roads region and Virginia’s Eastern Shore. Randy Ricker, vice president of Optima Health Community Care, says the deal gives the state some certainty about what it will be spending. “They pay us a capitated rate each month, and that allows the state to set a budget,” he says.

Optima has leased space in the Military Circle Mall in Norfolk, which will house about 200 employees. Each employee will handle a number of cases.

Suzanne Coyner, director for program care services for Optima Health Community Care, says the new care coordinators have diverse backgrounds. They include registered nurses (RNs) and licensed practical nurses (LPNs) along with people with backgrounds in social work and mental health.

The amount of involvement the coordinators might have in the lives of recipients can go pretty far. Besides the management of their changing health-care needs, recipients sometimes need help with more basic issues, such as paying a utility bill or finding the right support group.

Amanda Becker, director of behavioral health and addiction services for Optima, recalls a recipient who needed help arranging for home pest control, which can be a health issue. “Coordination is key,” she says. “We’re able to identify gaps because we’re looking from the top down.”

Jones says DMAS officials have spent a lot of time talking to providers in preparing for this program. “The main reason somebody might give us blowback is they’re afraid they might not make as much money, which is not true if they’re a quality provider,” she says.

Similar work is underway now across the rest of Virginia. The central region of the commonwealth launches the program Sept. 1, and by Dec. 1 CCC Plus will be at least started everywhere. “My goal, a personal and professional goal, was to get to this point where these Medicaid clients have comprehensive care and coordination,” Jones says.

Optima is part of Sentara Health Plans. The other insurance companies contracted with DMAS to handle CCC Plus are Aetna Better Health of Virginia, Anthem HealthKeepers Plus, Magellan Complete Care of Virginia, United Healthcare and Virginia Premier Health Plan.

In general, the Medicaid program has long been under pressure from Republicans. The resistance to Medicaid stiffened after a 2012 Supreme Court ruling allowing states to refuse to expand Medicaid under the ACA. Bill Howell, the retiring speaker of the House of Delegates, successfully led the blockade against expansion in Virginia. “Medicaid costs are out of control, patients are not receiving the quality care they deserve, and the program is plagued by waste, fraud and abuse,” he wrote in a 2014 newspaper column.

Jones says Medicaid expansion opponents wanted a political victory, no matter what the practical outcome was. “What they fell back on is: ‘The current Medicaid program is unsustainable so we have to reform that first.’ So that was their excuse. But once they gave us 19 things to do, and we accomplished those, then they moved the goalposts and said, ‘We need to see if it works.’”

Jones says her department has shown that Medicaid is efficient and effective and CCC Plus shows it is working to get more efficient. She reminds critics of what is at stake. “I always say the current Medicaid program [helps] babies, pregnant women, seniors and people with disabilities. Which one do you throw off the train?”

Jill A. Hanken also is tired of Medicaid criticism. She is director of the Virginia Poverty Law Center’s Center for Healthy Communities.

“Medicaid isn’t broken,” she says. Evaluations from the Joint Legislative Audit & Review Commission have supported that conclusion. One recent JLARC review, Hanken says, found $30 million in improper spending, about 0.4 percent of the Medicaid budget. “But $30 million in the context of a $9 billion program … it’s not something you want to support, but it’s not terrible.”

One in eight Virginia residents uses Medicaid benefits, according to DMAS. Two out of every three residents in nursing facilities use it, too. That ratio is a big deal, considering the aging baby boomer population and the increasingly high cost of private-sector, long-term-care insurance. “There always needs to be oversight and review,” Hanken says. “That doesn’t mean there’s anything wrong, but there’s always room to improve it. But you can’t lose sight of the value of the program.”

Paino came to Mary Washington from Truman State University in Kirksville, Mo., a school of 6,200 students where he had served as president for six years.

Paino came to Mary Washington from Truman State University in Kirksville, Mo., a school of 6,200 students where he had served as president for six years. With a new president, the university also has a number of new faces. In July, Nina Mikhalevsky became its new provost, the chief academic officer. She holds a tenured position as a philosophy professor at UMW. Starting this fall, Kimberly Young will be the new director of Continuing and Professional Studies. She headed executive education and executive MBA programs at the Henry W.

With a new president, the university also has a number of new faces. In July, Nina Mikhalevsky became its new provost, the chief academic officer. She holds a tenured position as a philosophy professor at UMW. Starting this fall, Kimberly Young will be the new director of Continuing and Professional Studies. She headed executive education and executive MBA programs at the Henry W. The Virginia legislation requires regular review and evaluation of all major incentives, including grants and tax preferences. That includes measuring the economic benefits to Virginia of the total spending on economic development initiatives at least every other year.

The Virginia legislation requires regular review and evaluation of all major incentives, including grants and tax preferences. That includes measuring the economic benefits to Virginia of the total spending on economic development initiatives at least every other year. Maynard says Virginia’s new effort means that every year a number of incentive programs will be evaluated, and she called JLARC “well-equipped” to do the work. “They really have a strong track record already” of studying the effectiveness of incentive programs.

Maynard says Virginia’s new effort means that every year a number of incentive programs will be evaluated, and she called JLARC “well-equipped” to do the work. “They really have a strong track record already” of studying the effectiveness of incentive programs. Dan Clemente, a Northern Virginia developer who is VEDP's board chairman, is fine with those recommendations. But he thinks that the report has become too much of a political weapon. Republican politicians, for example, have used it to attack the gubernatorial candidacy of Democratic Lt. Gov. Ralph Northam, who wants to succeed McAuliffe. Northam is an ex-officio member of the VEDP board.

Dan Clemente, a Northern Virginia developer who is VEDP's board chairman, is fine with those recommendations. But he thinks that the report has become too much of a political weapon. Republican politicians, for example, have used it to attack the gubernatorial candidacy of Democratic Lt. Gov. Ralph Northam, who wants to succeed McAuliffe. Northam is an ex-officio member of the VEDP board. The $40 million, 125,000-square-foot redo of the old Waterside Festival Marketplace into a dining and entertainment venue broke ground in mid-2015. The mixed-use development with restaurants, live entertainment and views of the Elizabeth River is expected to open in April. It will eventually employ about 1,000 people and is keeping a lot of subcontractors busy. “We have local plumbers, local electricians,” Sutch says.

The $40 million, 125,000-square-foot redo of the old Waterside Festival Marketplace into a dining and entertainment venue broke ground in mid-2015. The mixed-use development with restaurants, live entertainment and views of the Elizabeth River is expected to open in April. It will eventually employ about 1,000 people and is keeping a lot of subcontractors busy. “We have local plumbers, local electricians,” Sutch says. One of the largest projects under construction in Virginia is the $1.3 billion Greensville County Power Station. Dominion Virginia Power broke ground in June on its new natural gas-combined cycle power station, which should be operational in 2018. It’s located on a 1,143-acre site that straddles Greensville and Brunswick counties. When complete, the station is expected to produce enough power for 400,000 homes.

One of the largest projects under construction in Virginia is the $1.3 billion Greensville County Power Station. Dominion Virginia Power broke ground in June on its new natural gas-combined cycle power station, which should be operational in 2018. It’s located on a 1,143-acre site that straddles Greensville and Brunswick counties. When complete, the station is expected to produce enough power for 400,000 homes. The expanded use of focused ultrasound is an important development. “It opens the door for [treating] Parkinson’s disease and epilepsy and all those other” conditions related to brain function, says Dr. Neal Kassell, the founder and chairman of the foundation and a professor of neurosurgery at the University of Virginia.

The expanded use of focused ultrasound is an important development. “It opens the door for [treating] Parkinson’s disease and epilepsy and all those other” conditions related to brain function, says Dr. Neal Kassell, the founder and chairman of the foundation and a professor of neurosurgery at the University of Virginia. Dr. Peter Bastone, Chesapeake Regional’s CEO, recently reflected on its challenges near the end of his tenure at the hospital. He was scheduled to leave at the end of March to be closer to his family in California. Dr. Alton Stocks, Chesapeake’s chief operating officer, is now interim president and CEO.

Dr. Peter Bastone, Chesapeake Regional’s CEO, recently reflected on its challenges near the end of his tenure at the hospital. He was scheduled to leave at the end of March to be closer to his family in California. Dr. Alton Stocks, Chesapeake’s chief operating officer, is now interim president and CEO. Carilion CFO Don Halliwill cites several financial headwinds the hospital faces. The cuts in Medicare reimbursements, the lack of Medicaid expansion and the loss of commercially insured patients are the main issues. Unemployment in Tazewell County was 7 percent in December, compared with 3.9 percent statewide, according to Virginia Employment Commission figures, which are not adjusted for seasonal changes in the labor force. The jobless rates in neighboring Buchanan and Dickenson counties were both above 10 percent, the only two localities in Virginia with double-digit rates.

Carilion CFO Don Halliwill cites several financial headwinds the hospital faces. The cuts in Medicare reimbursements, the lack of Medicaid expansion and the loss of commercially insured patients are the main issues. Unemployment in Tazewell County was 7 percent in December, compared with 3.9 percent statewide, according to Virginia Employment Commission figures, which are not adjusted for seasonal changes in the labor force. The jobless rates in neighboring Buchanan and Dickenson counties were both above 10 percent, the only two localities in Virginia with double-digit rates. The Tazewell hospital also struggles to keep doctors in the area, both specialists and primary-care providers, he says. A primary-care doctor in a rural region generally is paid less than a physician in a practice in a wealthier and more populated community. And the work demands can be higher.

The Tazewell hospital also struggles to keep doctors in the area, both specialists and primary-care providers, he says. A primary-care doctor in a rural region generally is paid less than a physician in a practice in a wealthier and more populated community. And the work demands can be higher.