“If we sleep in on a Saturday, it’s a pretty rare thing,” says Highland County resident Sarah Collins-Simmons, “because we’re either farming or working on one of our [rental] properties.”

Born in bucolic Nelson County, Collins-Simmons, 31, now lives with her husband, Josh Simmons, in remote, rural Highland, a mountainous county bordering West Virginia. Known for its natural beauty, Highland has the distinction of being the state’s least-populated county, with fewer than 2,300 residents, including about 200 children enrolled in the county school system.

Collins-Simmons, who holds a master’s degree in landscape architecture from the University of Virginia, works as the orchardist and production supervisor for Big Fish Cider Co. in Monterey, the county seat.

Her husband, a Highland County native, worked for years as an independent contractor, doing carpentry, electrical and plumbing jobs about an hour southeast in Staunton, until he landed one of the rare full-time jobs in Highland offering health benefits. He’s now the county’s one-man building inspections and zoning department.

To help make ends meet, the couple work a few other jobs on the side, ranging from managing a farm for a military family stationed overseas to fixing up and renting investment properties.

“I love rural life,” Collins-Simmons says. “People that choose to live here tend to be enterprising and try to make the best of it. … To live a rural lifestyle, you have to be motivated, driven and enterprising. You may not have the opportunity for a full-time position, but there are plenty of opportunities to make good work for yourself if you are self-motivated.”

As Virginia’s unemployment rate fell to a 17-year low of 2.8 percent in December, rural counties such as Bath, Grayson, Highland and Nelson reported rates below 3 percent, just like localities in economic powerhouse regions such as Northern Virginia and Richmond. Overall, 76 cities and counties had jobless rates under 3 percent during December.

Nonetheless, economists and local officials say the numbers in rural areas and smaller cities can be deceptive, masking their struggles to retain young, working-age adults with 21st-century skill sets.

“We are pleased to see the unemployment rate continue to decrease in Virginia and believe it is a strong testament to the caliber of our workforce,” says Barry DuVal, president and CEO of the Virginia Chamber of Commerce.

“In 2017, while developing Blueprint Virginia 2025, the Virginia Chamber of Commerce traveled throughout the commonwealth listening to the needs of employers and the feedback we received was that access to workforce talent is on the top of every employer’s mind,” he says. “While all regions of Virginia are not growing at the same rate, all regions are growing and for that we are grateful. While we have a lot to be proud of, it is also important to recognize that there is much left to do in order to reposition Virginia, once again, as the best state for business.”

‘Growth begets growth’

Virginia’s employment boom is largely driven by the “Golden Crescent,” an urban swath running from Northern Virginia to Hampton Roads where employers in industries ranging from tech to retail to construction compete for workers in the tight labor market.

“Growth begets growth” in areas like Northern Virginia, where a highly skilled workforce once connected to federal contractors now attracts droves of technology companies, says Ann Macheras, group vice president with responsibility for microeconomics and research communications in the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond’s research department.

Unemployment in December 2018 dipped to 1.7 percent and 2.1 percent, respectively, in prosperous Arlington and Fairfax counties.

Amazon’s much-publicized HQ2 headquarters in Arlington and Alexandria will create an estimated 25,000 jobs in Northern Virginia, with an average salary of $150,000 — many of them highly skilled technology positions. And Virginia’s state government and technology business leaders have been saying for the past few years that the technology industry has a pressing need for as many as 17,000 cybersecurity professionals in Virginia, mostly in Northern Virginia’s tech hub.

The competition to fill technology jobs also is fierce in the Richmond metro area, where December unemployment rates in suburban Chesterfield and Henrico counties were 2.5 and 2.3 percent, respectively.

“We’re actually in the process of making an offer to a student who hasn’t even graduated yet, but we want to lock him in and make sure that he comes to us once he finishes his degree,” says Aaron Mathes, the Richmond-based vice president of mid-Atlantic business operations for CGI, a global information technology services firm.

“As the economy has picked up … the ability to retain [workers] is a bit more challenging, but frankly [in] the IT workforce, it’s been difficult to recruit for a long time. This is a highly competitive, sought-after set of skills.”

A missing workforce

Even though the unemployment numbers are similar in Virginia’s rural counties and smaller cities, the situation on the ground is much different.

“In rural areas where employment has remained steady or increased, the [age] 18-to-34 population has still declined in recent decades,” says Hamilton Lombard, a state demographer and research specialist for the Demographics Research Group at the University of Virginia Weldon Cooper Center for Public Service. (According to Census data, Virginia’s largest concentrations of 18- to 34-year-olds are located in metro Richmond, Northern Virginia and Hampton Roads.)

Even regions that encountered major employment losses during the past 20 years, such as Martinsville and Danville areas, posted December jobless rates of 3.4 and 3.6 percent, respectively. Nonetheless, Lombard says, those numbers don’t reflect the fact that “a much larger share of their population [is] just not in the workforce,” compared with the state’s larger metropolitan areas.

For example, 33 percent of people from ages 16 to 64 in rural Henry County aren’t participating in the labor force, compared with 20 percent in suburban areas such as Fairfax and Henrico counties. And the ranks of those not seeking jobs are similar in other rural localities, such as Highland (29 percent), Grayson (33 percent) and Smyth (34 percent) counties.

This is due to a variety of factors, says Lombard, including out-migration of young working-age adults looking for better employment opportunities elsewhere.

Additionally, many older people who lost factory jobs in the early 2000s have chosen to retire early in their 50s and 60s, either because they couldn’t find new jobs that paid as well as their old jobs or they didn’t have the training, skills or desire to switch careers late in life. A significant number of retirees also move to rural areas from metro areas. (In Highland, for example, where the median age of the population is about 53 years old, about half of the county’s housing stock is owned by retirees and owners of vacation homes who visit during the summer and fall.)

Rural localities also have more disabled working-age adults as well as greater numbers of stay-at-home parents, Lombard says. (Home schooling rates are as high as 10 percent in some rural Virginia counties, he points out.) And other factors also come into play that skew the numbers of people not participating in the labor force, such as the fact that most of the state’s prisons and regional jails are in rural areas.

In Southern Virginia, about 30 percent of adults not in the workforce live in “group quarters” facilities such as prisons and nursing homes, Lombard says. For example, Greensville County, home to Greensville Correctional Center, counts 52 percent of its population outside the workforce. (For census purposes, inmates are counted as local residents.)

So, what does the employment landscape look like in Virginia’s rural counties and smaller cities?

Long commutes

In many areas, it means commuting long distances for work and losing college-educated younger people to bigger metro areas.

In rural Russell County, skilled software developers with computer-science degrees commute from as far away as Kingsport, Tenn., and Bluefield, W.Va., to work at CGI’s information technology center, which employs about 400 people in Lebanon.

“It is challenging to find … jobs in the computer science field [in rural localities,]” says Angela Costagliola, manager of consulting delivery at the CGI center. “When CGI came here to Russell County, it was having corporate America in your backyard without having to move to a major city. … Students from college often think they have to move to Northern Virginia for a [job] in IT, but this does allow for them to come back to their grassroots and have a career in Russell County.”

Rural people “will drive one hour for a good-paying job,” says Mecklenburg County Administrator H. Wayne Carter III. “The vast majority of [Mecklenburg residents] who are looking for full-time employment have been able to find it,” he says, but some have to commute south to North Carolina’s Research Triangle.

Rural people “will drive one hour for a good-paying job,” says Mecklenburg County Administrator H. Wayne Carter III. “The vast majority of [Mecklenburg residents] who are looking for full-time employment have been able to find it,” he says, but some have to commute south to North Carolina’s Research Triangle.

Also like many other rural localities, Mecklenburg lost thousands of manufacturing jobs to factory closures between 2000 and 2011, and recovery has been slow. “While the economy has gotten a lot better in more urban areas, we lag behind,” Carter says. “We always have, even before the recession. We’ve always lagged behind several years, so it takes a while when the economy gets good for it to catch up to us.”

In January, Microsoft announced it would add 100 jobs at its Mecklenburg data center, the sixth expansion since 2010 at the facility, which already employs 300 people.

But the data center’s more skilled employees won’t necessarily come from Mecklenburg, Carter acknowledges. The county has fewer technologically skilled workers, despite the fact that its two high schools and area community colleges are teaching computer coding. Holding on to college-educated Mecklenburg natives also is challenging.

“It’s hard to keep your young people here without a huge base of job opportunities for them,” Carter says. “When they can move to a more urban area or suburban area like Chesterfield and have 12 different job offers versus one here, it’s hard to keep them here for that.”

One store for groceries

Infrastructure and amenities also are problems for these communities.

Monterey is pretty much the only place in Highland County where you can get a cellphone signal. It’s also one of only two areas in the county with water and sewer. The Dollar General there is the only store in the county where residents can buy groceries. Highland’s broadband internet access is better than in most rural Virginia localities, and the county is working to get high-speed, fiber-optic internet installed within the next decade. Nonetheless, lack of infrastructure makes it difficult to attract businesses to Highland, says Nancy Witschey, a member of the county’s economic development authority.

Also, there aren’t many opportunities for young adults to meet friends and date locally. As a result, some young professionals like physicians rarely stay long. “Life in Highland centers around the home, the church and the school,” Witschey says.

Full-time jobs in the county are difficult to find. The top employers are the county government and school system. The biggest private employer, a bank, has fewer than 20 workers.

Underemployment is also prevalent in rural areas, especially for college-educated people, says Robin Sullenberger, the retired CEO of the Shenandoah Valley Partnership, an economic development organization. He also is a former member of the Highland County Board of Supervisors. “Frankly, a lot of people in many rural areas … have just given up on any expectations that there are going to be quality jobs available to them, so they take other steps to provide for their families and make some amount of money regardless of whether it’s a sustainable wage or not.”

Many work odd jobs or hold multiple part-time jobs, either because full-time work isn’t available or they need flexible schedules so that they can also farm, Sullenberger says.

“My sarcastic bumper sticker is ‘Great place to live, hard place to make a living,’” says Betty Mitchell, Highland’s volunteer economic development officer.

21st-century skills

While there is no quick way to fill the opportunity gap between Virginia’s rural and metro communities, officials say the answer lies in creating diversified local economies and providing workers with 21st-century skills.

Rural America once provided the backbone of the nation’s manufacturing workforce, but technological advances have eliminated the large numbers of factory jobs that once fueled small cities like Martinsville and Danville. So, rural communities need to stay relevant by investing in workforce training, says Matthew Rowe, Pittsylvania County’s economic development director.

Pittsylvania recently has been on a roll, announcing more than $60 million in new investments during the past year, with 874 jobs with average salaries of $56,000. “You can live like a king in Southside Virginia on $56,000 a year,” Rowe says. But there’s one problem: Pittsylvania doesn’t have enough skilled workers to meet demand.

Pittsylvania and Danville teamed up with industry officials to develop workforce training initiatives in middle schools, high schools, Danville Community College and the Institute for Advanced Learning and Research. These training programs focus on areas such as machining, automation, welding and coding/cybersecurity.

The initiatives have been supported by more than $30 million in funding from state, local and federal governments as well as private industry. The programs largely have trained young adults, says Troy Simpson, director of advanced manufacturing at the Institute for Advanced Learning and Research, though a much smaller number of older adults also have enrolled to gain job skills.

Danville-area native Conner Lester, 25, is an example of this new workforce. He is a solutions and optimization engineer at Kyocera SGS Tech Hub, an advanced-machining research center that opened last year in Danville. He went through Danville Community College’s precision machining program and was encouraged to pursue an engineering degree at Virginia Tech. Without the community college program, he says, “I definitely wouldn’t be where I am now.”

Jason Wells, Kyocera’s lead executive in Danville, has been flooded with applications from Danville natives who would like to return. His local employees, he says, come from families with strong work ethics modeled by relatives who once worked in textile mills and on tobacco farms. And the area’s workforce training program, he says, has done an excellent job producing skilled workers. Until recently, however, many of them had to commute to jobs in Lynchburg or Greensboro, N.C., or move out of the area.

Danville once was a textile town, but employment at Dan River mills dwindled from 12,000 jobs in the 1950s to about 2,000 when the company closed operations in 2006. Today the city’s biggest employer is Goodyear, which has about 2,400 employees at a tire factory that recently celebrated its 50th anniversary.

Former Danville Mayor Linwood Wright, who now serves as an economic development consultant, says that his city survived job losses by creating a workforce with skills that aren’t dependent on a particular industry.

“The most important single asset for economic development is a trained workforce. I have been involved in locating a textile operation in a community that did not have an adequate labor force, and it was one of the biggest mistakes we ever made. I know what happens when you try to put a plant where you don’t have people to operate the plant,” he says. Providing his area’s workforce with training in areas such as precision machining and cybersecurity, Wright says, is what “we’ve got to do to be prosperous in the 21st century.”

Virginia Tech’s Jeffrey Alwang, a professor of agricultural and applied economics, agrees that the key to closing the gap between the large metro regions and smaller communities is investment in high-quality workforce education opportunities.

“The most critical area that needs to be addressed is the disparity between the prosperous areas of the state and the [struggling, rural] areas,” says Alwang. “Not only because it’s the right thing to do, but because the future of the economy of those areas depends on better trained workers, and if they’re not being educated, they’re going to be a drag on the rest of the state as time goes on.”

“You probably can eliminate the data-entry people. You can eliminate probably the first line of supervision. Whereas before you may have had several accounts-payable supervisors, now you may only have one [person] running automated accounts payable,” says Douglas E. Ziegenfuss, chair and professor of accounting at Old Dominion University.

“You probably can eliminate the data-entry people. You can eliminate probably the first line of supervision. Whereas before you may have had several accounts-payable supervisors, now you may only have one [person] running automated accounts payable,” says Douglas E. Ziegenfuss, chair and professor of accounting at Old Dominion University.

Rural people “will drive one hour for a good-paying job,” says Mecklenburg County Administrator H. Wayne Carter III. “The vast majority of [Mecklenburg residents] who are looking for full-time employment have been able to find it,” he says, but some have to commute south to North Carolina’s Research Triangle.

Rural people “will drive one hour for a good-paying job,” says Mecklenburg County Administrator H. Wayne Carter III. “The vast majority of [Mecklenburg residents] who are looking for full-time employment have been able to find it,” he says, but some have to commute south to North Carolina’s Research Triangle. As artificial intelligence inevitably eclipses human intelligence, that, too, is something that tomorrow’s business leaders will need to consider in grappling with future challenges posed by super-intelligent machines, says Anton Korinek. An associate professor of business administration at University of Virginia’s Darden School of Business, Korinek is teaching a class about A.I. and the future of work, including, he says, “what to expect in terms of future developments in our economy and how students can best prepare to face the world in which A.I. is going to take over larger and larger parts of our economy.”

As artificial intelligence inevitably eclipses human intelligence, that, too, is something that tomorrow’s business leaders will need to consider in grappling with future challenges posed by super-intelligent machines, says Anton Korinek. An associate professor of business administration at University of Virginia’s Darden School of Business, Korinek is teaching a class about A.I. and the future of work, including, he says, “what to expect in terms of future developments in our economy and how students can best prepare to face the world in which A.I. is going to take over larger and larger parts of our economy.” Harbor Park “became a great win-win for the [team] and the city,” says former Norfolk Mayor Paul Fraim, who helped put the city’s stadium deal together. “I think it’s been pretty much a model of a good public-private partnership in professional sports.”

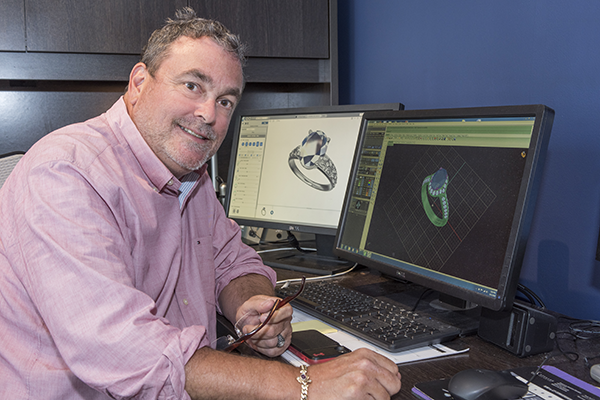

Harbor Park “became a great win-win for the [team] and the city,” says former Norfolk Mayor Paul Fraim, who helped put the city’s stadium deal together. “I think it’s been pretty much a model of a good public-private partnership in professional sports.” Since it opened in July 2017, Norfolk’s Percolator has opened four coworking spaces serving about 55 member companies, including David Nygaard Jewelers, whose namesake owner decided to close his longtime retail storefront in favor of working out of a Percolator office and seeing clients by appointment only.

Since it opened in July 2017, Norfolk’s Percolator has opened four coworking spaces serving about 55 member companies, including David Nygaard Jewelers, whose namesake owner decided to close his longtime retail storefront in favor of working out of a Percolator office and seeing clients by appointment only. “Quality of life is becoming more important for companies in attracting talent to this region,” says Barry Matherly, president and CEO of the Greater Richmond Partnership. And as companies look at factors that would attract desirable millennial and Gen Z workers to the region, they are noting that Richmond lacks a facility for larger music and pro-sports events.

“Quality of life is becoming more important for companies in attracting talent to this region,” says Barry Matherly, president and CEO of the Greater Richmond Partnership. And as companies look at factors that would attract desirable millennial and Gen Z workers to the region, they are noting that Richmond lacks a facility for larger music and pro-sports events. The effort would “create a walkable urban center” and connect the city’s economically depressed East End with new employment opportunities, Kelley says. And, he adds, “If it goes forward, it will be the biggest minority-business opportunity in Richmond history. Somewhere around $170 million will be set aside for minority contractors.”

The effort would “create a walkable urban center” and connect the city’s economically depressed East End with new employment opportunities, Kelley says. And, he adds, “If it goes forward, it will be the biggest minority-business opportunity in Richmond history. Somewhere around $170 million will be set aside for minority contractors.” Another way that Richmond is working to become more appealing to younger professionals, Matherly says, is with transportation projects such as the Greater Richmond Transit Co.’s recently launched Pulse rapid bus transit service. The Pulse runs for 7.6 miles along Richmond’s Broad Street corridor from Rocketts Landing in the east to the Willow Lawn shopping center near the Henrico County line in the west.

Another way that Richmond is working to become more appealing to younger professionals, Matherly says, is with transportation projects such as the Greater Richmond Transit Co.’s recently launched Pulse rapid bus transit service. The Pulse runs for 7.6 miles along Richmond’s Broad Street corridor from Rocketts Landing in the east to the Willow Lawn shopping center near the Henrico County line in the west. “Increasingly, RIC is seeing growing demand for overnight aircraft parking positions. Late-night arrivals become the next morning’s kick-off flights,” says Jon E. Mathiasen, president and CEO of the Capital Region Airport Commission. “While the airport can meet current requirements, the goal is to stay a bit ahead of the demand curve to meet foreseeable future needs.”

“Increasingly, RIC is seeing growing demand for overnight aircraft parking positions. Late-night arrivals become the next morning’s kick-off flights,” says Jon E. Mathiasen, president and CEO of the Capital Region Airport Commission. “While the airport can meet current requirements, the goal is to stay a bit ahead of the demand curve to meet foreseeable future needs.” For example, Newport Beach, Calif.-based Panattoni Development Co. is building 1 million square feet of speculative warehouse space on 62 acres near the Port of Virginia’s Richmond Marine Terminal along Interstate 95.

For example, Newport Beach, Calif.-based Panattoni Development Co. is building 1 million square feet of speculative warehouse space on 62 acres near the Port of Virginia’s Richmond Marine Terminal along Interstate 95. The institute “adds to the reputation that Richmond, Va., and the region is a forward-looking, progressive business community,” says Richmond philanthropist William A. Royall Jr., who donated $5 million to VCU for the project with his wife, Pam.

The institute “adds to the reputation that Richmond, Va., and the region is a forward-looking, progressive business community,” says Richmond philanthropist William A. Royall Jr., who donated $5 million to VCU for the project with his wife, Pam. Richmond is enjoying a renaissance as an in-demand city for tourists, and much of that reputation was built on the arts, says Jack Berry, president and CEO of Richmond Region Tourism.

Richmond is enjoying a renaissance as an in-demand city for tourists, and much of that reputation was built on the arts, says Jack Berry, president and CEO of Richmond Region Tourism. “Terracotta Army,” the VMFA’s recent traveling exhibit of archaeological treasures from the reign of the first emperor of China, drew more than 204,000 visitors and brought in about $3 million in ticket sales and museum gift shop purchases alone, along with $500,000 in new memberships.

“Terracotta Army,” the VMFA’s recent traveling exhibit of archaeological treasures from the reign of the first emperor of China, drew more than 204,000 visitors and brought in about $3 million in ticket sales and museum gift shop purchases alone, along with $500,000 in new memberships. “Arts in general and theater in particular are definitely an economic driver in downtown [Staunton],” says Amy Wratchford, managing director of the American Shakespeare Center. “The relationship between the theater and the city and the other arts organizations in the area is very strong. We do a lot of cross-marketing.”

“Arts in general and theater in particular are definitely an economic driver in downtown [Staunton],” says Amy Wratchford, managing director of the American Shakespeare Center. “The relationship between the theater and the city and the other arts organizations in the area is very strong. We do a lot of cross-marketing.” Wolf Trap has an annual economic impact of about $80 million in Fairfax County, including tax revenue and ancillary activities such as dining and lodging. “That translates to just under a thousand full-time equivalent jobs generated by the activity of Wolf Trap,” says Arvind Manocha, the president and CEO of the Wolf Trap Foundation for the Performing Arts.

Wolf Trap has an annual economic impact of about $80 million in Fairfax County, including tax revenue and ancillary activities such as dining and lodging. “That translates to just under a thousand full-time equivalent jobs generated by the activity of Wolf Trap,” says Arvind Manocha, the president and CEO of the Wolf Trap Foundation for the Performing Arts. In fact, “as people were preparing for tax reform, there were a lot of people that were making big year-end gifts … because they weren’t sure what was going to happen. So, the end of the year was very good” for charitable giving, says Keith Curtis, the immediate past chair of the Giving USA Foundation. He is the founder and president of The Curtis Group, a Virginia Beach-based fundraising consulting firm.

In fact, “as people were preparing for tax reform, there were a lot of people that were making big year-end gifts … because they weren’t sure what was going to happen. So, the end of the year was very good” for charitable giving, says Keith Curtis, the immediate past chair of the Giving USA Foundation. He is the founder and president of The Curtis Group, a Virginia Beach-based fundraising consulting firm. Geoffrey G. Hemphill, a tax attorney with Norfolk-based Vandeventer Black LLP, says it’s far from clear what impact, if any, the tax overhaul will have. Not getting a tax benefit won’t stop his own charitable giving, Hemphill says, “and I suspect a lot of people are like that. I’m still going to give to my church, and I don’t care what the loss of a deduction is. … I always thought charity was a matter of the heart and not a matter of your personal wallet.”

Geoffrey G. Hemphill, a tax attorney with Norfolk-based Vandeventer Black LLP, says it’s far from clear what impact, if any, the tax overhaul will have. Not getting a tax benefit won’t stop his own charitable giving, Hemphill says, “and I suspect a lot of people are like that. I’m still going to give to my church, and I don’t care what the loss of a deduction is. … I always thought charity was a matter of the heart and not a matter of your personal wallet.”