Last spring Marc Edwards got a call from a mother in Flint, Mich., who said the city’s water supply was poisoning her children. It was the second time in his life that he had gotten such a call. And this time the municipal water safety expert knew exactly what to do.

Call in a student research team. Use a crowdfunding campaign to buy water filters for Flint residents. File freedom of information requests that would reveal mismanagement in the midst of a dangerous public-health crisis.

Edwards had been seasoned by an earlier lead-poisoning crusade in the early 2000s in Washington, D.C., that also began with a call from a concerned mother. His work there helped spark a congressional probe that in 2010 concluded that the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention had knowingly used flawed data in claiming that the district’s drinking water posed no health risk.

So the Virginia Tech professor of civil and environmental engineering lost no time in exposing what he says was “a clear example of environmental injustice” in Flint.

“It’s probably the clearest example of a failure by government civil servants in our country’s history, where both federal and state public health agencies, engineers and civil servants, betrayed a city. They broke the law; they covered it up. They would have continued to let the kids drink the water and destroy the city’s vital infrastructure.”

Flint is a poor city. Its population has dwindled from 200,000 to fewer than 100,000 as auto jobs have gone away. More than half of the city’s population is African-American, and more than 40 percent of the residents live in poverty.

The city’s water problem began in April 2014 when a state-appointed emergency manager authorized switching Flint’s water supply from Detroit’s municipal system to the Flint River, as a cost-saving measure. The switch was supposed to be temporary until a new pipeline could be completed that would have drawn water from Lake Huron. The river water was more corrosive than Detroit’s system, and state regulators did not require the use of an anti-corrosive chemical. So lead leached into Flint’s water supply from aging lead pipes.

The city’s water problem began in April 2014 when a state-appointed emergency manager authorized switching Flint’s water supply from Detroit’s municipal system to the Flint River, as a cost-saving measure. The switch was supposed to be temporary until a new pipeline could be completed that would have drawn water from Lake Huron. The river water was more corrosive than Detroit’s system, and state regulators did not require the use of an anti-corrosive chemical. So lead leached into Flint’s water supply from aging lead pipes.

While state and federal officials assured residents that the water was safe, LeeAnne Walters, a Flint mother of four, claimed that the city’s rust-colored water was making her children sick.

She was right. Nearly 9,000 children in Flint are believed to have been exposed during an 18-month window — from April 2014 to October 2015 — to lead levels that far exceeded safe limits. According to Edwards’ tests from Walters’ home, the highest lead level was more than 13,000 parts per billion (ppb). The level considered actionable by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) is 15 ppb. The safe lead level is zero ppb. That’s because lead is a toxic metal considered hazardous to children, potentially causing long-term, irreversible neurological damage.

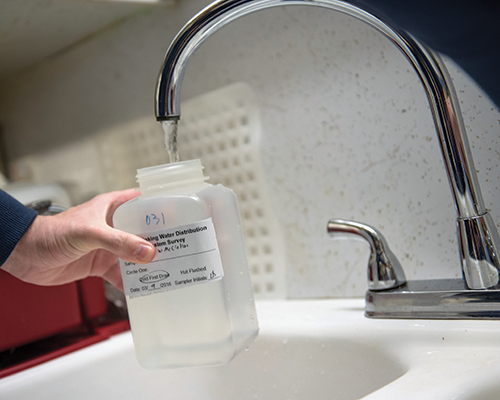

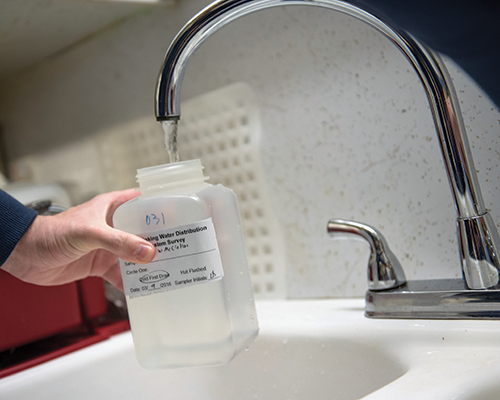

When Edwards decided to help Flint, he made it a teachable moment by involving his students. A 25-member student research team made four trips to Flint where they met with residents, tested water samples and warned against drinking unfiltered water.

In October 2015 — six weeks after Edwards’ Tech team first visited Flint — Michigan officials declared a public health emergency and switched Flint’s supply back to Detroit. The fallout continues, with the crisis prompting a criminal probe, lawsuits and calls for the resignation of Michigan Gov. Rick Snyder. In April, Michigan’s attorney general filed criminal charges against two state environmental regulators and a Flint water plant supervisor that include allegations of tampering with water-monitoring reports.

For Siddhartha Roy, a 27-year-old graduate student, the experience has been “life changing.” Roy led the student team and created a website, FlintWaterStudy.org, to keep residents informed, applying what he had learned in the classroom to a real-world situation. “It has taught us the value of listening to the public, to the voices of those who are disenfranchised.”

Instead of making him cynical, Roy says, the crisis creates hope. “Now we are having national conversations on what it means to have safe water.”

Tech’s Flint Water Study Team continues to test for lead in the water. The city is receiving federal disaster relief funds and other help to rebuild its aging water system and to mitigate the health harm to children.

Throughout the crisis, Edwards played a high-profile role. He testified before Congress on his findings and is serving on a governor-appointed task force that’s devising a long-term strategy to address Flint’s water system.

With all the publicity, many accolades have come his way. Time magazine recently included Edwards and Dr. Mona Hanna-Attisha, a Flint pediatrician who also sounded the alarm after seeing elevated lead levels in children, on its list of the world’s “100 Most Influential People.” Edwards also appears on Forbes 2016 list of “World’s Greatest Leaders.”

The 51-year-old professor shakes off the celebrity. “I’m just a regular guy,” he insists, who feels “lucky” that he hasn’t been fired by Tech because of all the time he has spent on the D.C. and Flint water cases.

The 51-year-old professor shakes off the celebrity. “I’m just a regular guy,” he insists, who feels “lucky” that he hasn’t been fired by Tech because of all the time he has spent on the D.C. and Flint water cases.

“The horror of this injustice — you don’t feel like celebrating or that you won anything,” he says. “You just desperately try to prevent it from happening again. The EPA to this day has not apologized, has not acknowledged its role in what happened in D.C. or Flint. Until that happens there is no hope that another Flint will not occur. It will occur. The miracle in Flint was they got caught.”

Flint may well be a watershed moment for the country. It offers an opportunity to carve out a new model not only for cities with old infrastructure but also for fast-growing, water-conserving cities. In both cases, notes Edwards, water is sitting around longer in pipes, which increases the risk that something will go wrong.

He plans to take a sabbatical next year to write a book about Flint, which he envisions as a case study about what went wrong.

Virginia Business interviewed Edwards in May in Blacksburg. He also gave an interview to VB’s sister publication, Roanoke Business.

VB: When you were invited to Flint in May to hear President Barack Obama’s remarks, what was that like for you?

Edwards: It was good. I’m glad he went to Flint because I think it sent a statement. Hopefully an example of environmental injustice really speaks to all Americans, and it bothers everybody. I think everyone’s trying to sort out how and why this could happen in the United States, and he gave his perspective on that, but the key point was it was historic. He went and said that Flint counted.

VB: So is the water safe now?

Edwards: The water is still not meeting federal standards. We tested in March, and the lead levels are too high. What’s happened is pieces of lead are still falling off the plumbing into the water at random intervals more so than in other cities. Nowadays everyone knows existing federal standards are not very protective, so to be exceeding that is a real problem.

VB: Should we change the standard?

Edwards: That’s a cost-benefit analysis debate that people have to make. I would argue it should be tightened, but there’s no magic pot of money to fix all these problems … I think a consensus has emerged that we need a tougher law, but what makes me upset is we’re not following existing law. If we followed the existing law, these tragedies that I’ve been working on never would have happened.

VB: What about the 9,000 children who were exposed? Will they suffer irreversible damage?

Edwards: Some kids are going to suffer the consequences for their whole life, but I think that’s the minority of children, thankfully. This was caught early on. I shudder to think what would have happened if we hadn’t intervened because the lead was just starting to fall off into the water at high levels. The incidence of blood lead poisoning was skyrocketing in the months that we got involved, and kids would still be drinking that water to this day. So, it could have been another Washington, D.C., type tragedy. Washington, D.C., [had] about 30 times more lead-poisoned children, 30 times worse than Flint.

VB: Will someone follow the children to see how they’re doing?

Edwards: Yes, they’re getting help. There’s roughly $150 million being invested to mitigate the health concerns, provide extra health services, expand Medicare and Medicaid. Dr. Mona [Hanna-Attisha] has a Flint Children’s Fund; it’s privately overseen money of $10 million or so. This is quite a big contribution to the future of the children of Flint … The D.C. kids got nothing. Their families got not one penny. Having lived through that makes the D.C. story a little bit more tragic to me, but the point is we showed kids [in Flint] were getting hurt. The agencies and the state, normal people, stepped up to help them. That was heartening, and we got kids protected. We avoided the worst of the harm.

VB: At this point, what do you think is the ideal resolution for Flint?

Edwards: There’s really no precedent. We’re going to have to ask society to debate and decide what kind of behavior we’re going to tolerate in government officials … They not only allow it to occur, they enable it to occur, actively covering this problem up … Certainly the state — the state agency employees, engineers and scientists whose job it is to make sure that this never happened — you know they’re primarily responsible for what happened, but without EPA they would have never been able to take it as far as they did.

VB: So should we do away with the EPA and, if so, what is the alternative?

Edwards: I get criticized by both sides because the two options most commonly put on the table are, one, get rid of the EPA; or two, give EPA more money. I’m sorry neither of those is reasonable. There’s a corrupt culture throughout our government agencies. We see it in the Veterans Administration. We see it at the IRS. We see it at the Centers for Disease Control. They covered up the lead crisis in D.C. with a falsified scientific report. [In 2010, a House investigative inquiry into D.C.’s lead water problems earlier in the decade determined that the CDC made “scientifically indefensible” claims in 2004 when it said that children were not being harmed by high levels of lead in the water.] We see it at EPA. Good people are not leading these agencies. Good people are getting fired for doing their job. Unethical, lying cowards seem to rise to the top of these agencies. So when something like Flint happens people are shocked and I say, “if this is how you run your agency, destroying good people and promoting bad people, what do you expect?”

VB: What should we do to prevent another Flint?

Edwards: You have to fire some bad people. When EPA testified to Congress and said they had nothing to do with Flint, under oath, that they were strong-armed by the state … You know, it’s Orwellian, it’s absurd. Why do we allow them to get away with this? … If the only way we fire a bad actor is after they poison a city, 12 people die, they destroy the vital infrastructure and then you become an international embarrassment, that’s what it takes to lose your job?

VB: You’ve been appointed by Michigan’s governor to serve on the Flint Water Interagency Coordinating Committee. Could you tell me about that?

Edwards: We’re trying to find our way through mitigating an unprecedented manmade disasters. There is no blueprint. It’s not like a hurricane where you can do what you did during the last hurricane. What are the appropriate steps to help the city get back on its feet? How can we best invest the money?

VB: How much money has been allocated?

Edwards: There’s been like a few hundred million, and that’s half of what’s needed. There’s no way the people in Flint can pay to fix what happened. The damage is just too great. The water bills are already the highest in the U.S. … [The water crisis] put the city in a death spiral because you’ve got people leaving, and they don’t have enough people to pay for the water system as it is. Plus, you’ve got $100 million dollars in damage to the water system. So, the city is not financially sustainable. It was on life support before this, and this was like pulling the plug. Without outside help, there’s no way the city and its residents can ever hope to get a financially sustainable water system.

VB: Is the job of the committee to develop a sustainable model?

Edwards: That’s an infrastructure question. How can we fix the infrastructure where the current residents can afford to pay their water bill and get healthy water? This is no small task. This is a major challenge because the water system was designed for a population 2½ to 3 times higher than it is now and, the more oversized the system, the harder it is to keep the water healthy because it sits around a long time. It’s got old pipes, and dirt is getting in. I mean they’re having 500 main breaks a year. It’s very cost ineffective. They’re working overtime just to repair breaking water systems.

VB: It sounds like you’re talking about a major investment in the infrastructure, or do you just get rid of it and start from scratch?

Edwards: There’s like four or five different approaches. Someone has to sit down and say, “What are the cost/benefits, detriments of each approach?” I’m hoping we get enough money to give Flint a fighting chance.

VB: Could the work of the committee become a model for other cities?

Edwards: Yes, we hopefully can learn from this tragedy. It’s an extreme case, but you learn the most in extreme cases in science and engineering. Flint was ahead of the curve in terms of going bankrupt. Cutting the water infrastructure is the first place you cut when you’ve got to make hard decisions. But the other sides of this are two extremes that Flint can help us understand. One is the whole decaying bankrupt path, in which the parallels are obvious, but also there are newer cities, particularly California. They are undergoing very, very stringent conservation [because of an extended drought.] What this does is create the same oversized system. When you have green buildings, and you have everyone conserving, it takes a very long time for the water — from the time it leaves the treatment plant — to get to where you use it.

VB: It takes a very long time for what?

Edwards: If you’re using less water, and you’ve got your old water system, it takes a longer time for the water to move from the treatment plant to your tap … So, if you use half the water, it takes twice as long to get there.

VB: So it’s just sitting in the pipes?

Edwards: Yes. It’s kind of like milk. Milk sits around, it goes bad. When water takes longer to move from one place to another, it tends to go bad. The pipes degrade its quality. You can get diseases, you know, things like Legionnaires can grow more easily. We’re arguing that what we can learn from Flint can help cities of the future. So, part of fixing Flint is maybe changing the pipe size so the water moves faster, getting smaller pipes. That’s just one example.

VB: What a teaching moment for a professor. What do you hope your students took away from this?

Edwards: I have this class on engineering ethics that I co-teach. We teach students to plan how they will react when, not if, but when they encounter nonethical behavior. We teach them the high cost that you will pay if you speak out. … The students come through the class, and most of them say it was a transformative experience for them because we taught them to see where they would have been willfully blind. In school and in our institutions, we really do teach people to be willfully blind, to look the other way … So, the fascinating thing was that, [in] the five years that I taught this class, in my mind I was refighting the D.C. lead crisis. That took me 12 years, 25 hours a week, pretty much on my own. So, I was thinking, how would I refight the D.C. lead crisis if I could? And then it [Flint] came up. I mean the parallels are just unbelievable.

So I said, “This is our class project.” Not only will we teach ethics and talk about the D.C. lead crisis; we’re going to have this Flint water crisis experience. Plus, I had students from three prior years of class, and I said this is like your practicum… Again it was like refighting D.C. and actually winning, not that you can win.

VB: How did that feel this time around?

Edwards: It was a totally different experience because 12 years versus six weeks is a whole lot easier. Plus, you protect the kids in the end, because in D.C., the kids got hurt right in front of you … You couldn’t counter the power of those agencies to lie and do harm. The interesting part for me was, when I tell the D.C. story in class, I [always say] that I know this is depressing … and then, when we went to Flint, I’m telling them it never happens this way. Do not think that this is how it works because you do not overcome the power of the state and the federal government in six weeks and live to tell the tale the vast majority of the time.

VB: Is Flint a warning sign of things to come?

Edwards: Lead in water is a problem all over the U.S. because EPA has allowed the water companies to cheat for 10 years. So, if you look in the paper, you’ll see about problems in Philadelphia; Chicago; Jackson, Miss.; Sebring, Ohio. In every major urban center, if people look at what’s going on, they’re going to be shocked at what they see because people have been told their water is safe when it’s not.

We have a law that’s not being followed. It’s an example of the agency dysfunction and the lack of trustworthiness I think that’s destroying trust in science and engineering in America. It’s destroying people’s trust in government. That’s the huge problem. The thing we have to do is change the culture of these agencies so they are worthy of the public trust. It’s not an alternative to just throw more money at them or to get rid of them. You have to get these agencies fixed.

VB: Let’s switch gears to Virginia. Is the drinking water in Virginia safe? Are there places here where water should be a concern?

Edwards: I haven’t encountered this kind of unethical behavior in Virginia agencies. When the D.C. lead crisis occurred, for example, Montgomery County schools decided to go out and test every tap, and they fixed the problem. I was like, “Wow, this is how it should work.”

VB: And that was 10 or 12 years ago?

Edwards: Yes. Now they’re testing it again … I’m just saying by comparison to what I’m running into in these other places, Virginia looks like a good place to live.

VB: Do you feel battle worn at this point? You have been involved in some type of a lead water controversy for a long time.

Edwards: There have been times it’s been very, very hard. I have everything going for me, an amazing family, great students, great colleagues. Virginia Tech has been great. They didn’t fire me, but even so … the financial repercussions are hard to deal with. At the same time, I feel that I’m the most optimistic person on the planet. I really feel we’re going to get this fixed because failure is not an option.

VB: So you haven’t given up?

Edwards: You know, as I say many times, to wake up every day with such a sense of purpose and feel like you’re doing the job you’re born to do, I wouldn’t trade it for anything, but I wouldn’t wish it on anyone either.

VB: What kind of an impact has the publicity from Flint had on Va. Tech?

Edwards: I don’t think there’s been a science story like this ever. I think it’s been viewed very positively … There’s something in Flint that makes every American angry. There’s no one that will defend what happened in Flint … I think it’s been good for the school. In some ways it does define what Virginia Tech aspires to … This is a model for a modern land-grant [university] as an institution where you can do science as a public good, serving people, correcting injustices. Now, that can never be your bread and butter, but if everyone devotes a small percent of their time to something, that can make a huge difference.

VB: Is this still your perfect job?

Edwards: Yes. I’ve got the best job in the world. I love what I do. It doesn’t mean, I’m blindly optimistic, a Pollyanna, because, you know, I call it like I see it, but I really feel I’ve got the best job. Virginia Tech has been amazing to me. I’ve got great students, great friends. I wouldn’t change a thing.

VB: Are you being recruited by other schools?

Edwards: I know I would have options if I wanted to go other places, but Virginia Tech suits me. I’m a blue-collar guy. I love our students. Virginia Tech has stood by me, so it would be really, really hard to leave.

VB: What happened in Flint seems like a story made for Hollywood. Has anyone called you?

Edwards: We’ve already had about 25 documentaries go through Virginia Tech.

VB: You mean people have come and interviewed you all about this?

Edwards: Yes. This is going to be one of the best-documented things in history. I can’t even keep track of them all, but we accommodate anyone who wants to go through.

VB: Has anyone from Hollywood called to say we want to make a movie about you?

Edwards: Oh yeah, they’ve called. Once a week someone’s calling about a movie or a book.

VB: What do you think about that?

Edwards: Well, I’m writing an imaginary book right now. Everyone thinks they’re going to write a book, so that’s why I call them imaginary books. I’m thinking of just pulling out the highlights and the lowlights of this journey. Whether it’s just a really lousy case study that I write up, I haven’t decided. I’m focused right now on helping Flint recover. That’s got to be my highest priority. My next highest priority is to try to start doing my job, which you know I haven’t really done in a year. I was going to write a book about D.C., and I probably would have been writing that had Flint not happened. It’s interesting because the problem with writing the D.C. book was I didn’t have an ending. I obviously have an ending now. Whether I ever get around to doing that… I tell myself I will. There are not enough hours in the day because I'm helping with these disasters.

VB: You describe yourself as a normal guy trying to do your job, but you have been hailed as a national hero. What do you think of all the celebrity? Do you still feel like a regular guy?

Edwards: I am a regular guy. I don’t believe any of it. I mean after you survive something like D.C., and you saw what happened to so many people who did the right thing and lost their careers … Five people who kind of alerted the public lost their jobs. That’s why I say, good people, heroic people, are getting fired for doing the right thing. So in time you learn that for every thousand people that go this path only one comes out of it whole to the extent that I am whole. So you don’t really feel like — what you feel like is you’re honoring the sacrifice of all the people that did not make it, all the kids.

VB: Why do you think you came out whole?

Edwards: Well, I’m world class stubborn. If there was a gold medal for stubbornness … I was lucky. I was smart. I had everything going for me. I mean the MacArthur money, [a $500,000 genius grant from the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation] that was a big deal. So I really did have everything imaginable … The betrayal of these agencies of the public trust is so profound and disturbing … The horror of this injustice, you don’t’ feel like celebrating or that you won anything. You just desperately try to prevent it from happening again. The EPA to this day has not apologized, has not acknowledged its role in what happened in D.C. or Flint. Until that happens there is no hope that another Flint will not occur. It will occur. The miracle in Flint was they got caught.

VB: And they got caught because a mother picked up the phone?

Edwards: Yes, and we were here ready to do the unthinkable. In a billion years they never thought someone would do what we did. You know we’re not in a position to do it again. This costs a lot of money …

VB: I read that you spent a quarter of million dollars (from his discretionary research funds at Virginia Tech) helping to expose the Flint water crisis? Did you get some of that back?

Edwards: We got back about $160,000 [ from a crowdfunding initiative] … The total we paid as of February amounts to six person years of effort for Flint. I haven’t written a grant in a year basically. It’s not just what you paid, and what you didn’t get back. It’s also how much time you’re spending on it without your cash flows drying up. Again, I’ve got no complaints. It was priceless. It had to be done. There’s so much more work to be done and so, you know, the whole celebrity thing, it’s kind of interesting how many people are fascinated by it.

VB: Because so many people stumble and fall when they become celebrities?

Edwards: Well, maybe yeah. That will never happen. If you’re a survivor …

VB: That’s how you see yourself, as a survivor?

Edwards: Absolutely. If you read about the Greatest Generation, those guys that survived World War II, they didn’t think they were heroes. They just felt lucky they came home. I’ve seen some really horrible things. It’s not hard to stay grounded, especially when you’re surrounded by good people.

The city’s water problem began in April 2014 when a state-appointed emergency manager authorized switching Flint’s water supply from Detroit’s municipal system to the Flint River, as a cost-saving measure. The switch was supposed to be temporary until a new pipeline could be completed that would have drawn water from Lake Huron. The river water was more corrosive than Detroit’s system, and state regulators did not require the use of an anti-corrosive chemical. So lead leached into Flint’s water supply from aging lead pipes.

The city’s water problem began in April 2014 when a state-appointed emergency manager authorized switching Flint’s water supply from Detroit’s municipal system to the Flint River, as a cost-saving measure. The switch was supposed to be temporary until a new pipeline could be completed that would have drawn water from Lake Huron. The river water was more corrosive than Detroit’s system, and state regulators did not require the use of an anti-corrosive chemical. So lead leached into Flint’s water supply from aging lead pipes. The 51-year-old professor shakes off the celebrity. “I’m just a regular guy,” he insists, who feels “lucky” that he hasn’t been fired by Tech because of all the time he has spent on the D.C. and Flint water cases.

The 51-year-old professor shakes off the celebrity. “I’m just a regular guy,” he insists, who feels “lucky” that he hasn’t been fired by Tech because of all the time he has spent on the D.C. and Flint water cases.