After a year-long search and frenzied speculation over where Amazon Inc. would locate a second corporate headquarters, Northern Virginia beat out a slew of other contenders Tuesday to land a fat slice of the pie.

In separate announcements, Gov. Ralph Northam and Amazon said the tech giant will invest $2.5 billion to establish a major headquarters in the state that is expected to create more than 25,000 high-paying jobs over 12 years.

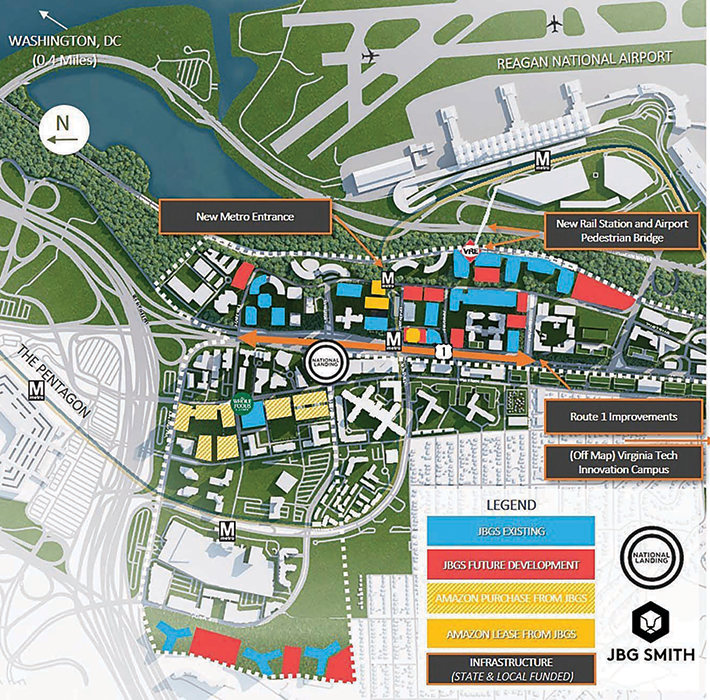

The headquarters will be housed at National Landing, a joint site in Arlington County and Potomac Yard in Alexandria.

The announcements ended months of suspense over where Amazon would locate a second, $5 billion headquarters that promised 50,000 high-paying jobs and an 8 million-square-foot campus. Ultimately, the tech giant decided to split the headquarters between Northern Virginia and the Queens neighborhood of Long Island City in New York.

While news of the split decision leaked over the past few days, Tuesday’s announcements brought new details about one of the most highly anticipated corporate location decisions of the 21st century.

“This is a big win for Virginia — I’m proud Amazon recognizes the tremendous assets the commonwealth has to offer and plans to deepen its roots here,” Northam says. “Virginia put together a proposal that we believe represents a new model of economic development for the 21st century … The majority of Virginia’s partnership proposal consists of investments in our education and transportation infrastructure that will bolster the features that make Virginia so attractive: a strong and talented workforce, a stable and competitive business climate, and a world-class higher education system.”

Amazon said it plans to locate in 4 million square feet in Northern Virginia, with the opportunity to expand to 8 million square feet. The company said its investment and job creation should produce more than $3.2 billion in new state general fund revenues during the next 20 years.

In return, Amazon said it will receive performance-based direct incentives of $573 million based on the company creating 25,000 jobs with an average pay of more than $150,000 in Arlington. This includes a workforce cash grant from the commonwealth of up to $550 million based on $22,000 for each job created. Amazon would receive the incentive only if it creates the projected high-paying jobs. According to state officials, the package comes out to 6 to 1 return on investment over the term of the performance-based agreement.

The company also is slated to receive a cash grant from Arlington of $23 million over 15 years based on the incremental growth of the existing local transient occupancy tax, a tax on hotel rooms.

In its announcement about selecting two cities, Amazon said it can recruit more top talent by being in two locations. “These are fantastic locations that attract a lot of great talent,” the company said.

To woo the much-coveted headquarters, Virginia also offered $195 million in transportation projects to improve mobility in Northern Virginia, including additional entrances to Metro stations at Crystal City and Potomac Yard. In addition, Arlington and Alexandria plan to fund more than $570 million for transportation projects, including rail connections and transit facilities serving the site.

Virginia officials and business leaders celebrated the news, saying Amazon’s presence will make Northern Virginia a top East Coast technology hub and lift Virginia’s national profile as a desirable location among corporate recruiters. “Anyone that moves in 25,000 jobs will move the needle and make this much more of a tech hub. It will be great for this marketplace,” says Bob Kettler, chairman and CEO of Kettler, a commercial real estate development company in McLean.

Holly Sullivan, Amazon director of WW economic development, said in a statement: “We are looking forward to joining the community and are excited to be creating high-paying jobs in Arlington. We believe that northern Virginia is a great place for our teams to keep inventing on behalf of our customers.”

The quest to land Amazon involved hundreds of people working collaboratively across the state. The Virginia Economic Development Partnership (VEDP) collaborated with Arlington County, the city of Alexandria, the General Assembly’s Major Employment and Investment (MEI) Project Approval Commission and local, regional and state partners.

Northern Virginia’s proposal included four sites in the Alexandria, Arlington County, Fairfax County and Loudoun County. National Landing, the winning location, was proposed as a joint partnership between the Alexandria and Arlington.

Stephen Moret, VEDP’s president and CEO, lauded the cooperative efforts, saying that it laid the groundwork for Virginia’s success. “The tech-talent pipeline investments that Gov. Northam and the General Assembly are launching will position communities across the commonwealth for healthier, more diversified economic growth,” he says.

The backbone of the cooperative pitch for Amazon’s headquarters is a long-term strategic investment of more than $1 billion in public higher education institutions to double the annual number of graduates with bachelor’s and master’s degrees in computer science and closely-related fields, ultimately yielding 25,000 to 35,000 additional graduates, above current levels, during the next two decades.

“Winning Amazon’s major new headquarters is a significant accomplishment for Virginia and it’s technology sector,” says Sen. Frank Ruff, R-Mecklenburg County and chairman of the MEI Commission, which reviews and approves major state incentive packages. “The jobs might be in Northern Virginia, but the revenues that will come are going to help us finance education, public safety, mental health, all the important issues,” he says in an interview with Virginia Business.

‘Deal of the century’

“In some ways, it is the deal of the century,” says Bill Quinby, vice chairman and co-regional manager of the Washington, D.C., office of Savills Studley, a commercial real estate services firm with offices across the country. “It’s tech; it’s retail; it’s everything. Consequently, Amazon is going to be as competitive and a bit of a monopoly maker as some of the greats going back a century.”

From the start, Northern Virginia was considered a top contender because of its deep pool of tech talent. According to Cushman & Wakefield’s 2018 Tech Cities report, the metro D.C. region has 327,273 tech workers, second only to New York with 491,419. With an office market of more than 300 million square feet that in recent years has seen higher-than-normal vacancies as a result of the federal government’s sequestration, it also has enough space to absorb a large headquarters.

Amazon already employs more than 2,000 people in Northern Virginia in technical and corporate jobs, and it has nearly 100 data centers in Loudon County that are either on the ground, being constructed or in the planning stages.

Plus, Amazon’s founder and CEO Jeff Bezos has ties to the region. He owns The Washington Post and a $23 million property in D.C.’s Kalorama neighborhood that he’s renovating into a home.

In addition, Amazon is locating its East Coast campus for cloud computing, Amazon Web Services, to Fairfax County. While the company is best known as the world’s largest online retailer, the fast-growing cloud computing division generated $1.6 billion, or 55 percent, of the company’s third-quarter operating income of $3.7 billion.

When Amazon announced its short list of 20 cities in January, Northern Virginia, Washington, D.C., and Montgomery County, Md., all made the list. Jason Miller, CEO of the Greater Washington Partnership, characterized Amazon’s decision as “an incredible win” for the entire region. “It is an important affirmation of our talent, our diversity, and our incredible potential. It also proves that the unprecedented unity among Maryland, the District, and Virginia sent a loud and clear message that we’re all in this together… When one wins, we all win.”

Arlington County Board Chair Katie Cristol said Amazon’s selection of the National Landing site validates the county’s strengths: sustainability, transit-oriented development, affordable housing, and diversity. “The strength of our workforce coupled with our proximity to the nation’s capital makes us an attractive business location,” she said in a statement.

Besides transportation improvements, Arlington and Alexandria also have committed to fund affordable housing, workforce housing and public infrastructure, relying on revenues generated from Amazon's presence in their communities. Combined, the localities project annual investments of more than $15 million over the next decade, resulting in the creation and preservation of 2,500 to 3,000 units in and around the Crystal City, Pentagon City and Columbia Pike areas and throughout Alexandria.

A key player in Amazon’s new home in Northern Virginia is JBG Smith, a real estate investment trust based in Chevy Chase, Md., and the main property owner of National Landing. The site offers more than 12 million square feet of existing office space and 13,000 residential units. It’s a walkable neighborhood that includes Crystal City, the eastern portion of Pentagon City and the northern portion of Potomac Yard. Situated across the Potomac River from Washington, D.C., it's considered one of the region's best-located, urban mixed-use communities.

JBG Smith controls more than 6.2 million square feet of the project’s development, primarily in Crystal City. Amazon intends to lease existing space and purchase land for development from the company in Crystal City and Pentagon City, while a new Virginia Tech Innovation Campus is expected to be developed in the Alexandria portion of National Landing.

“We are incredibly pleased to partner with Amazon on their new headquarters,” JBG Smith CEO Matt Kelly said in a statement. “It validates our placemaking and repositioning strategy in National Landing and will accelerate our plans to revitalize the area in a dramatic way.”

National Landing

National Landing checks off many requirements Amazon had in a second headquarters; namely an urban site with access to public transit that’s close to an airport. The area is within walking distance of Reagan National Airport. It has three Metro stations and a commuter rail station. Plus, Crystal City’s proximity to the Pentagon is seen as a plus at a time when Amazon’s cloud computing unit is vying for billion-dollar federal defense and intelligence contracts.

Many of the older office buildings in Crystal City originally were built for government agencies and contractors in the 1970s. After 2005, many large government tenants left as part of the Pentagon’s Base Closure and Realignment Commission (BRAC) process.

Recently, Arlington County approved major upgrades to Crystal City’s commercial center, Crystal Square. JBG plans a new four-story retail building anchored by an Alamo Drafthouse Cinema, the addition of a specialty grocery store and a public park. The company already has tried to punch up the area’s drab public exteriors by covering some of the office high-rises with colorful building wraps.

“The bones are there; it just needs to be built out,” says Sarah Dreyer, regional director of research for Savills Studley’s D.C. office. “There’s an opportunity for whoever comes to craft it on their own.”

Amazon says it would need at least a half a million square feet by the end of next year. Crystal City alone offers 8.6 million square feet of rentable space and has a vacancy rate of 20 percent.

JBG became the largest owner of commercial real estate in Crystal City as part of its July 2017 merger with Vornado Realty Trust’s D.C. business.

Dealing primarily with a single landlord “will make Amazon’s life a lot easier,” says Quinby of Savills Studley. “Putting these projects together is not simple. It’s time consuming and very capital intensive.”

Background

Amazon’s site selection sweepstakes began on Sept. 7, 2017. That’s when the company issued a request for proposals (RFP) inviting cities in North America to respond with bids. The deadline for submitting proposals for what came to be called HQ2 was Oct. 19. The process drew proposals from 238 localities across the U.S. and Canada. Amazon CEO and founder Bezos said at the time that its second headquarters campus would be “a full equal” to the company’s global headquarters campus in Seattle.

The Seattle site employs about 45,000 people in 33 buildings and is still growing. According to Amazon, the company has had an indirect impact of $38 billion in additional investment on Seattle’s economy. Yet, some residents there have been critical of the company, saying its presence has driven up housing prices and swamped the city’s infrastructure.

Perhaps because of those sentiments, Amazon decided to reduce its impact with two new headquarters instead of one. “We are excited to build new headquarters in New York City and Northern Virginia,” Bezos said in a statement. “These two locations will allow us to attract world-class talent that will help us to continue inventing for customers for years to come.”

To win the headquarters, some states such as Maryland and New Jersey reportedly each offered economic incentive packages of more than $5 billion. Following the open call, though, the quest to win HQ2 was shrouded in secrecy. Until Tuesday’ s announcement most states, including Virginia, refused to disclose what taxpayer incentive offers had been made for fear of tipping their hand to the competition. Nor would they make public what sites were being offered, in part because state officials and developers had signed nondisclosure agreements with Amazon.

According to Quinby of Savills Studley, who has been involved with several large corporate headquarter locations during his 40-year career, secrecy is typical on mega deals.

“To the public, I’m sure it does look like Amazon was the big bad wolf coming to town, and now it’s changing the rules,” he says since the company opted later in the game to split the headquarters.

“Yet, it wasn’t an uncommon approach. What made it different was because of who it was and the sheer size.”

Still, groups opposed to having Amazon’s second headquarters in the D.C. area didn’t take kindly to being kept in the dark about what was being offered to a company headed by one of the world’s richest men. Bezos took the top spot this year on Forbes magazine’s annual list of America’s wealthiest people with an estimated net worth of $160 billion.

Two local community groups, Our Revolution Arlington and the Northern Virginia branch of Metro DC Democratic Socialists of America, have been vocal about their opposition to Amazon locating its headquarters in the area. DSA NOVA’s Alex Howe says he’s glad that Virginia’s not offering as much money as Maryland planned to if it landed the deal. However, his group still opposes providing incentives to Amazon.

“Virginia, Arlington and Alexandria shouldn’t be subsidizing or giving money to the largest corporation in the world,” Howe says.

Our Revolution Arlington and DSA NOVA are working to make sure Amazon pays its fair share of the deal. That includes providing enough money for infrastructure improvements across the entire region and ensuring enough money for affordable housing in the area. The groups are hosting a town hall in December where members of the community can ask questions and express their concerns.

Some residents also are worried that housing prices will spike, much like what happened in Seattle. While the Northern Virginia suburbs have some of the highest median household incomes in the country, they also have some of the most expensive home prices. During the third quarter, the median price for a single-family home in Arlington was $855,000, according to a market report from the Long & Foster Cos. The median price for a townhome came in at $565,950, and buyers could expect to pay $360,000 for a condo or coop.

Amazon’s announcement should give the Northern Virginia real estate market a shot in the arm, which has plateaued recently despite a strong economy and tight labor supply, says Nick Ron, CEO of House Buyers of America Inc., based in Chantilly.

He also expects new housing to create pressure on home prices. “There’s going to be a supply problem,” said Ron. “It’s really hard to build housing for 25,000 people quickly.”

Land prices also have been increasing, he adds, which makes construction of affordable housing nearly impossible. “When you’re trying to build affordable housing, it’s really hard when land prices are high.”

The Metropolitan Washington Council of Governments says the region needs to add 235,000 housing units by 2025 to respond to expected job growth, even without Amazon.

Amazon is working with JBG Smith Properties Inc., a Chevy Chase, Md.-based real estate investment trust, as its leasing and development partner. “Our view is that this could change the center of gravity for the whole metro area,” says Matt Kelly, JBG’s CEO. “This is the largest-single employment driver we’ve had in this market in the form of one company coming in. We do expect a coattail effect with additional job growth and corporation relocations that we might attract here.”

Amazon is working with JBG Smith Properties Inc., a Chevy Chase, Md.-based real estate investment trust, as its leasing and development partner. “Our view is that this could change the center of gravity for the whole metro area,” says Matt Kelly, JBG’s CEO. “This is the largest-single employment driver we’ve had in this market in the form of one company coming in. We do expect a coattail effect with additional job growth and corporation relocations that we might attract here.”  JBG Smith owns 6.2 million square feet of existing office space and 7.4 million square feet of future development sites in National Landing. Situated across the Potomac River from Washington, D.C., it’s considered one of the region’s best-located, urban mixed-use communities.

JBG Smith owns 6.2 million square feet of existing office space and 7.4 million square feet of future development sites in National Landing. Situated across the Potomac River from Washington, D.C., it’s considered one of the region’s best-located, urban mixed-use communities.