A city famous for birthing country music and straddling the Virginia-Tennessee state line, Bristol, Virginia, has spent the last decade struggling to recover from the Great Recession and the coal industry’s steep decline.

However, a new surge of economic life is reenergizing Bristol as it enters the 2020s. More visitors are flocking downtown. A new college prepares to reopen a once-closed campus. And new industries seek to add new elements to the regional economy while reviving the shuttered Bristol Mall.

“Over the last 10 to 15 years, you’ve seen a great transformation in Bristol,” says Beth Rhinehart, president and CEO of the Bristol Chamber of Commerce, which represents the Virginia and Tenn-essee sides of the border. (Sometimes referred to as the “twin cities,” Bristol is neatly divided into Virginia and Tennessee cities, both named Bristol, both with their own governments. The iconic Bristol Virginia-Tennessee sign looms over State Street downtown, demarcating the state line and proclaiming it “A GOOD PLACE TO LIVE”).

Rhinehart was talking largely about the revitalization of Bristol’s downtown district into a destination for food, drink and culture, but an even bigger transformation may be in the offing if Bristol, Virginia, voters decide this November to allow a long-proposed casino to be built in the city.

Gambling on gaming

During its 2020 session, the Virginia General Assembly legalized casinos to operate in five economically challenged localities, including Bristol. Only one casino is allowed to operate in each locality. Gov. Northam indicated in early March that he intended to sign the casino legislation. However, it would still require approval by Bristol voters in a local referendum, to be placed on the ballot in November’s presidential election.

So far, the only casino project proposed for the city is the $400 million Hard Rock Casino Bristol, helmed by local businessmen Jim McGlothlin, CEO of The United Co., and Clyde Stacy, the president of Par Ventures LLC, both of whom have longtime ties to the coal industry and have been friends since high school. Hard Rock International, which would operate the casino, is an equity partner in the venture, which McGlothlin says would include a 100,000-square-foot convention center, 600-room hotel, and dozens of retail shops and restaurants.

If approved, the Hard Rock Casino Bristol will be built on the site of the former Bristol Mall, which opened in 1976 but closed in 2017 after losing anchor tenants such as JCPenney and Sears.

The Bristol City Council and School Board have both passed unanimous resolutions supporting the project, which would generate $130 million in revenue annually and create more than 1,000 direct jobs, according to a November 2019 study by the state Joint Legislative Audit and Review Commission (JLARC). McGlothlin says Bristol is struggling, even though it was removed from the Virginia comptroller’s list of fiscally distressed localities in 2019. The coal industry has significantly declined, hurting not just local companies in that sector, but also the stores and restaurants that benefited from miner families in nearby counties who patronized businesses in the region’s biggest metro area. Other major regional employers like Bristol Compressors Inc. have closed in recent years, and the city is mired in debt from investing heavily in The Falls, a retail project that’s struggled to attract big-name tenants.

“Virginia needs something to help this city,” McGlothlin says. “If we can build a resort here and have the engine powering it being a casino, it would be a win for everyone.”

The Hard Rock Casino Bristol proposal came under fire from Steve Johnson, a regional developer who has previously feuded with the Bristol, Virginia, city government. A former pro football player, Johnson developed The Pinnacle, a destination retail center just across the state line in Tennessee. Construction on The Pinnacle began in 2013, and Bass Pro Shops, its first anchor tenant, opened the next year. Its success inspired Bristol, Virginia, to launch The Falls shopping center — with outdoor retailer Cabela’s, a Bass Pro competitor at the time, as its anchor. But The Falls has largely fallen flat, with Cabela’s closing after it was acquired in 2017 by Bass Pro Shops.

Johnson is proposing a partnership with the North Carolina-based Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians to develop and open a $500 million casino resort complex on 350 acres next to The Pinnacle in Washington County, northeast of the city. The project would include a water park, a hotel, a gravity-powered mountain coaster and 100,000 square feet of retail.

The problem for Johnson is that the General Assembly’s casino legislation didn’t include Washington County in its list of eligible localities for casino development. The Cherokee can’t pursue a casino in Virginia through the federal Indian Gaming Regulatory Act, either; only the Pamunkey Indian tribe can do so in Virginia.

That leaves Gov. Ralph Northam as the last hope for Johnson’s casino proposal. Northam told the Bristol Herald Courier in March that he was “open-minded” to discussing it with Johnson. But opening the door to a Washington County casino would require Northam to amend or veto the already-passed casino legislation and send it back to the General Assembly for further consideration when the legislature reconvenes on April 22, a scenario that observers say may not be too likely.

Back to the ‘big bang’

Beyond the prospect of a casino, Bristol is seeing other transformations.

One of the biggest changes, says Rhinehart, has been a shift in where people spend their recreational time. Previously, they traveled to other communities for restaurants and nightlife. Now, they’re staying downtown.

Rhinehart works downtown in the chamber’s offices, but the resurgence snuck up on her. Driving downtown on a recent Thursday evening, she was surprised at the level of activity.

“There were people everywhere — people walking across the street, in every direction,” Rhinehart says. “You felt the energy of downtown that had been building and building.”

Much of that energy has come from Bristol’s focus on tourism, developing attractions such as the Birthplace of Country Music Museum, which opened downtown in 2014. The museum builds on Bristol’s legacy as the location for the pivotal 1927 recording sessions of The Carter Family and Jimmie Rodgers, now known as the “big bang of country music.” The Bristol sessions were prominently featured in Ken Burns’ 2019 “Country Music” documentary on PBS, which generated another round of publicity and visitors. Birthplace of Country Music Museum spokeswoman Charlene Baker says that history has become a rallying point for city residents.

“People recognize history and buy into it,” Baker says. “The museum has created community pride in a way that hadn’t been there before for the city.”

The museum has helped to make downtown an attraction that dovetails with other destinations such as the Bristol Motor Speedway, which hosts two major NASCAR weekends each year, as well as other races and events.

“The tourism economy has been that steady thread when a lot of other things have waxed and waned,” Rhinehart says. “I credit that in large part to marketing efforts, but also that we have the assets to market: the Birthplace of Country Music, Bristol Motor Speedway and a very vibrant downtown with a lot of microbreweries, distilleries, shopping and great restaurants.”

New boutique hotels opening in the downtown district offer a different style of lodging than the chains located along Interstate 81. Scheduled to open at the end of March, the 70-room, $20 million Sessions Hotel is housed in three historic buildings that have been renovated by Roanoke-based Creative Boutique Hotels and MB Contractors. The Sessions will build on Bristol’s music heritage by incorporating indoor and outdoor stages for live performances. It will also include a spa and barbecue restaurant.

The Sessions joins the $20 million, eight-story Bristol Hotel, a 100-year-old renovated building that was re-launched last year, as well as the Tenneva Hotel, a Holiday Inn-branded lodge just across the state line that broke ground in 2019.

Hitting a stride

As downtown Bristol is reinventing itself for a new era, the same thing is happening at the former Virginia Intermont College. The four-year private college lost its accreditation in 2013 and closed in 2014. Its former campus was bought in 2016 by Chinese businessman Zhiting Zhang and his company, the U.S. Magis International Education Center, which soon began the process of establishing a new college. The newly rechristened private Virginia Business College has received provisional approval by the State Council of Higher Education for Virginia and hopes to begin classes in August 2020.

VBC President Gene Couch says the college will offer bachelor’s degrees in business, with seven concentrations: accounting, business analytics, entrepreneurship, human resources management, information technology management, management/leadership and marketing. It will market itself as a four-year residential college, targeting students who live within a 90-minute drive of Bristol.

“One of the things we’re selling, especially to prospective students in the coalfields, is Bristol itself,” Couch says. “Bristol is unique: one city in two states. In addition, you’ve got South Holston Lake, motorsports with NASCAR here, and then the downtown area of breweries and art scene and theater and entertainment. We see students coming here to experience Bristol while they’re learning.”

And while Bristol officials are waiting for voters to decide whether to reinvent the Bristol Mall site into a Hard Rock casino, the mall is currently home to Dharma Pharmaceuticals. Backed in part by Clyde Stacy, it is one of five companies approved by the Virginia Board of Pharmacy to produce pharmaceutical products from cannabis.

The company opened last year in the shuttered mall’s former JCPenney location and has invested between $4 million and $10 million in the medical marijuana production facility. The company issued a news release last fall saying it would move to a new location if voters clear the way for the Hard Rock casino to be built at the mall site.

“Dharma Pharmaceuticals has a twofold mission,” says CEO Shanna Berry. “No. 1 is safe access to marijuana medication, and No. 2 is to create economic development and a really strong workforce in the area. We’re all native Virginians and have lived in the region our whole lives.”

The company was launched by Berry, who has worked in the real estate industry for 20 years, along with a real estate title specialist and a pharmacist.

“We saw a need,” Berry says, “based on where we’re at in the heart of the opioid crisis, to be able to make a small impact in an economically distressed city and simultaneously improve lives of people going through cancer, Parkinson’s and a multitude of chronic conditions that cannabis helps. To be able to do … those things simultaneously is very rewarding for us.”

Dharma Pharmaceuticals will grow cannabis plants, extract cannabidiol and THC-A oils, develop them into products and dispense them to customers through its pharmacy.

Dharma Pharmaceuticals, Virginia Business College, the boutique Sessions Hotel and the proposed Hard Rock casino all are parts of an emerging economy that Bristol leaders hope will propel the state-line metro hub into a new era of prosperity.

“Bristol was the most financially distressed city in all of Virginia two or three years ago, and they have made great strides to recover from that,” Rhinehart says. “Southwest Virginia is gritty in a good kind of way, in that we look out for one another. We know we have to bind together for economic development success.”

“Bristol has always been ‘The Little Engine That Could’ in a lot of ways,” says the Birthplace of Country Music Museum’s Baker. “It’s pretty magical. We’ve started to hit our stride.”

During the multiyear process, news leaked that Roanoke had made Deschutes’ short list, along with Charlottesville and Asheville, N.C. That led Michael Galliher, a local government employee and beer enthusiast, to start a social media movement. Residents and companies around the region filled social media with positive images of Roanoke, branded with Galliher’s hashtag, #Deschutes2Rke.

During the multiyear process, news leaked that Roanoke had made Deschutes’ short list, along with Charlottesville and Asheville, N.C. That led Michael Galliher, a local government employee and beer enthusiast, to start a social media movement. Residents and companies around the region filled social media with positive images of Roanoke, branded with Galliher’s hashtag, #Deschutes2Rke. Mechatronics incorporates mechanical systems, electrical systems and information technology into one career path. VWCC’s program includes a high-school component through the Regional Academy; a two-year certificate or associate degree through VWCC; transferability to four-year degrees at Old Dominion University and Purdue University Calumet; and Siemens mechatronics systems certification, which is highly sought by employers, especially in manufacturing.

Mechatronics incorporates mechanical systems, electrical systems and information technology into one career path. VWCC’s program includes a high-school component through the Regional Academy; a two-year certificate or associate degree through VWCC; transferability to four-year degrees at Old Dominion University and Purdue University Calumet; and Siemens mechatronics systems certification, which is highly sought by employers, especially in manufacturing. Up the road at The Falls, Lowe’s and Zaxby’s have followed Cabela’s, with more on the way, says developer Brent Roswall of Interstate Development. He pursues “category-killer” tenants, retailers that dominate in their fields.

Up the road at The Falls, Lowe’s and Zaxby’s have followed Cabela’s, with more on the way, says developer Brent Roswall of Interstate Development. He pursues “category-killer” tenants, retailers that dominate in their fields. “Sometimes you have people who remember downtown in its heyday in the ’40s and ’50s,” says Bristol Vice Mayor Bill Hartley. “It’s not exactly like it was back then, but there’s a lot of activity. You have a lot of different things coming downtown, breweries and boutique hotels, that really capture the essence of Bristol.”

“Sometimes you have people who remember downtown in its heyday in the ’40s and ’50s,” says Bristol Vice Mayor Bill Hartley. “It’s not exactly like it was back then, but there’s a lot of activity. You have a lot of different things coming downtown, breweries and boutique hotels, that really capture the essence of Bristol.” Josh Lewis, executive director of Virginia’s aCorridor, an economic development organization serving Bristol, Abingdon and a number of other nearby localities, says the creation and expansion of smaller companies is helping drive the local economy’s growth.

Josh Lewis, executive director of Virginia’s aCorridor, an economic development organization serving Bristol, Abingdon and a number of other nearby localities, says the creation and expansion of smaller companies is helping drive the local economy’s growth. The layoff of 600 workers at Volvo came about after the announcement of two major investments in the last two years, including a $69 million, 200-job deal to create a customer-experience track in 2014 and a $38 million, 32-job deal to build a related facility in 2015. The layoff announcements weren’t tied to economic overreach, but to a decline in demand for commercial trucks across the entirety of the North American market.

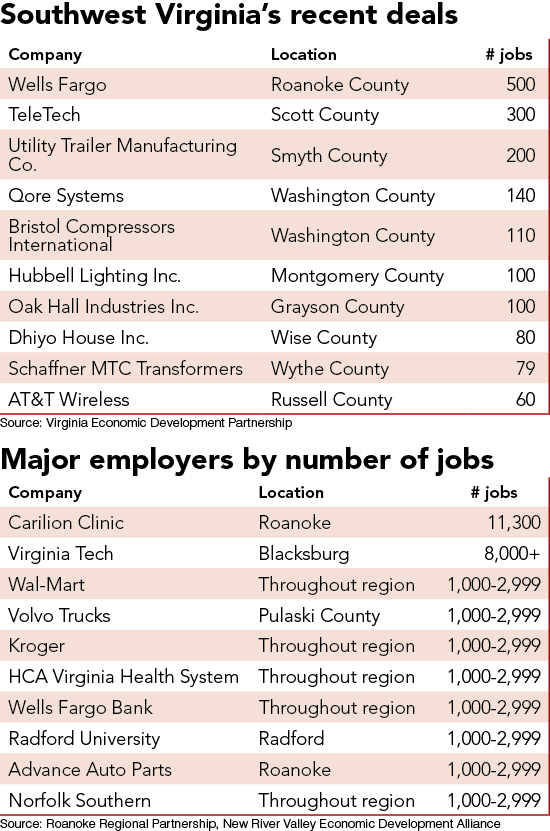

The layoff of 600 workers at Volvo came about after the announcement of two major investments in the last two years, including a $69 million, 200-job deal to create a customer-experience track in 2014 and a $38 million, 32-job deal to build a related facility in 2015. The layoff announcements weren’t tied to economic overreach, but to a decline in demand for commercial trucks across the entirety of the North American market. Health care long surpassed the railroad as the region’s largest industry. Carilion Clinic employs more than 10,000 people, followed by Virginia Tech with more than 8,000 jobs.

Health care long surpassed the railroad as the region’s largest industry. Carilion Clinic employs more than 10,000 people, followed by Virginia Tech with more than 8,000 jobs. Crowning Touch Senior Moving Services acts as a one-stop shop for seniors who are downsizing and moving to new living spaces. It handles all aspects of the move: transferring belongings, selling the old house as-is and assisting in disposing of unneeded items through auctions and its consignment store.

Crowning Touch Senior Moving Services acts as a one-stop shop for seniors who are downsizing and moving to new living spaces. It handles all aspects of the move: transferring belongings, selling the old house as-is and assisting in disposing of unneeded items through auctions and its consignment store.