As Tennessee created a buzz with its decision to offer all residents a free community college education, a proposal to study something similar for Virginia quietly died in a state Senate committee in February.

But one thing remains clear in Virginia, among Republicans and Democrats alike, says Glenn DuBois, chancellor of the Virginia Community College System. “Twelfth grade is no longer the finish line” because a postsecondary credential is what a high school diploma once was.

Much like the early 20th century when states wrestled with how to finance secondary public education, he says, Virginia now must decide “how to finance the new goal.”

“I don’t believe there is such a thing as free community college,” DuBois says. “Someone has to pay for it.”

In Tennessee, revenue from the state lottery is picking up the tab for the so-called “last dollar” of tuition and fees after scholarships and grants are exhausted.

The week after the resolution for a study in Virginia failed at the General Assembly, Tennessee Gov. Bill Haslam, a Republican, officially launched the expansion of a state program that has allowed recent high school graduates to enroll tuition-free at community and technical colleges. Beginning this fall, all Tennessee adults will be able to take advantage of the same free-tuition offer if they don’t already hold degrees.

“Free is kind of a relative term,” says Peter Blake, director of the State Council of Higher Education for Virginia.

A state may need to add little if any revenue after scholarships and federal Pell Grants, which help students with the most financial need, are applied, “and you can say that person has free tuition,” Blake says. “The advantage of what Tennessee did, in my judgment, is around marketing and telling Tennesseans that an education is achievable for them.”

Better-educated workers

The goal of the two Tennessee programs — Tennessee Promise for recent high school graduates and Reconnect for adults — is similar to Virginia’s effort to increase the number of residents with a postsecondary degree or credential.

According to the 2017 annual report for Tennessee Promise, which began in 2015, the program cost $25.3 million in 2016-17 and will rise to about $33 million this year. The estimated annual cost for Reconnect is $10 million.

During its last academic year, VCCS collected $460 million in tuition and mandatory fees, according to Jeffrey Kraus, assistant vice chancellor for strategic communications. Community college students were awarded $194 million in Pell Grants, although the funds can be used for educational expenses other than tuition and fees.

While “last dollar” references are often used to describe how free-tuition plans work, VCCS at this time does not collect data in that way and does not have an estimate on remaining need, Kraus says. But a report on the financial gap facing students is expected to be presented to the state board later this spring.

For Virginia, Blake questions what the impact might be on the state’s strong system of small private and regional public universities, which could lose enrollment if students opted to begin their studies at free community colleges rather than attend a four-year school. “Would you scramble the enrollment rather than broaden the base?” he says.

Movement in other states

The push for free community college has become a national issue. In his 2015 proposal for two years of free tuition, America’s College Promise, President Barack Obama cited estimates that by 2020 about 35 percent of job openings will require at least a bachelor’s degree and another 30 percent will require some college or an associate degree.

During the 2016 presidential campaign, Democratic candidate Bernie Sanders and nominee Hillary Clinton supported a debt-free community college option for students. President Donald Trump recently suggested community colleges revert to the term “vocational schools.”

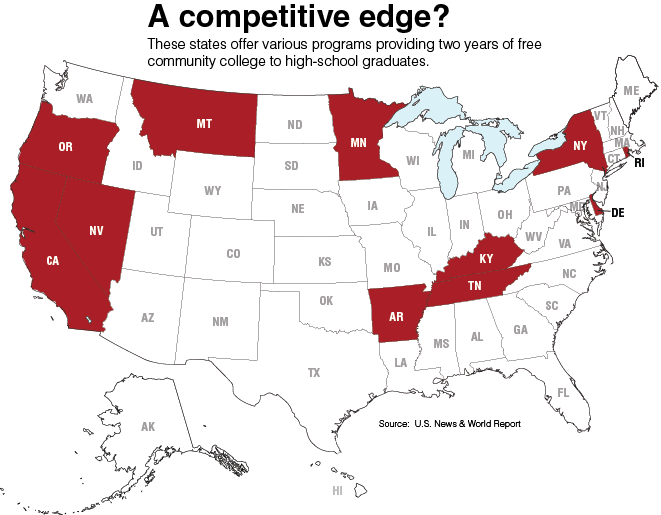

The free college idea, however, is taking hold in several states in various forms.

The free college idea, however, is taking hold in several states in various forms.

Tuition is waived at the two-year City College of San Francisco for students with California residency living in the city. New York’s Excelsior Scholarship covers tuition at two- and four-year state colleges for families or individuals earning up to $125,000 annually.

In January, the West Virginia Senate unanimously approved a bill making community and technical colleges free for residents, provided they pass a drug test. A fiscal analysis accompanying the bill estimated the cost at $8 million annually. (As this issue went to press, the bill was stalled in the state’s House of Delegates.)

The newly approved North Carolina Promise will cut tuition — but not fees — to $500 per semester for in-state students and to $2,500 for out-of-state students at three institutions in the University of North Carolina system.

Competitive advantage?

Donald J. Finley, president of the Virginia Business Higher Education Council, sees such efforts as producing a competitive advantage for neighboring states. “It has to be,” he says. “If they’re investing more in their workforce and making it easier for people to get the skills they need, then obviously they have an advantage that we would like to have.”

VBHEC has made affordable access a key component of its Growth4VA campaign to promote reform and reinvestment in Virginia’s higher education system.

“I’m a big fan of community colleges and what they have done for Virginians,” Finley says. But in over 20 years the system has gone from ranking as among the most affordable in the nation to among the least affordable. “That’s not a good thing,” he says.

VBHEC took no stand on the resolution proposed by state Sen. John S. Edwards, D-Roanoke, for the Joint Legislative Audit and Review Commission to study the feasibility of free community college tuition for Virginia residents.

The resolution, which Edwards also offered last session, was rejected by the Committee on Rules.

Edwards notes that it’s been more than a half century since Virginia enacted its first sales tax in 1966 to establish the community college system. The state has “a history of frugal government,” he says, but it needs to find a way to offer a free community college education not just for high-demand programs but “across the board. I think it’s that important.”

Northam’s G3 plan

One proposal in Gov. Ralph Northam’s successful gubernatorial campaign last fall would make community college and workforce training free for well-paid “new-collar jobs” in high-demand fields. Called G3 for Get Skilled, Get a Job and Give Back, the program would pay the student’s “last dollar” of tuition and fees but require a year of public service in exchange. The proposal did not become legislation this session, but Chancellor DuBois says discussions are underway on how to implement G3. “Stay tuned,” he says.

VCCS already has a pathway to a debt-free credential or degree at some community colleges through education foundations that provide scholarships for students graduating from high schools in their regions. New River Community College’s ACCE program, for example, is a public-private partnership that provides two years of tuition for students in participating counties.

And the General Assembly in 2016 approved the Workforce Credential Grant Program, which reduces student costs for specific credentials by two-thirds. In financing the program, lawmakers were adamant that students must have “skin in the game” by paying for a portion of their training.

While it’s valuable to look at all options to reduce the cost of education, Blake says, the policy debate for Virginia remains what is the most efficient use of limited public dollars to reach educational attainment goals.

“I don’t think there’s an appetite for widespread, wide-open, free community college,” he says.

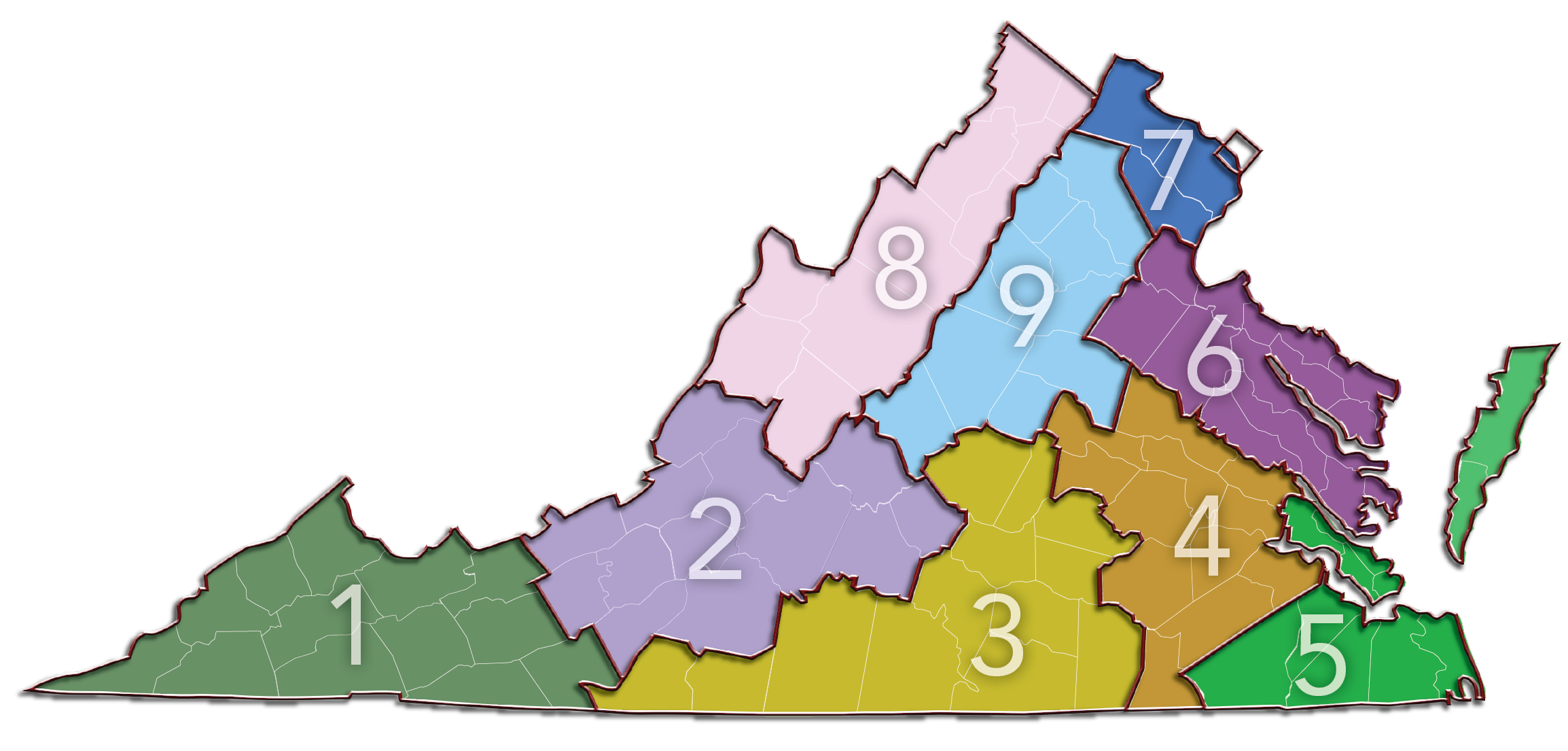

In September, the board overseeing the state program approved the growth and diversification plans submitted by nine regional councils.

In September, the board overseeing the state program approved the growth and diversification plans submitted by nine regional councils. Bill Shelton, DHCD’s director, says the regional plans focus on “best bets” for showing immediate results for job growth, as well as clusters of crosscutting industries with potential for longer-term growth.

Bill Shelton, DHCD’s director, says the regional plans focus on “best bets” for showing immediate results for job growth, as well as clusters of crosscutting industries with potential for longer-term growth. Fourth-largest college

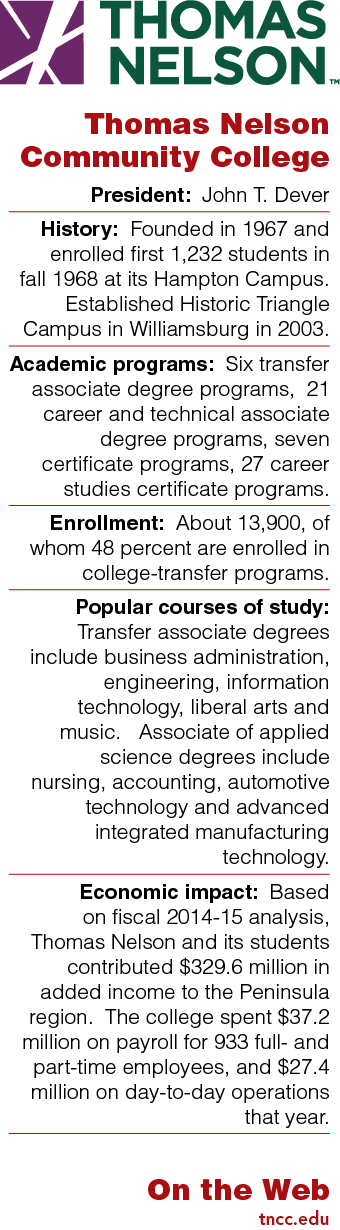

Fourth-largest college Manfred has a personal perspective on two of the career tracks students can follow. One of her twin sons is in a two-year, guaranteed-transfer program. He plans to go to Virginia Tech.

Manfred has a personal perspective on two of the career tracks students can follow. One of her twin sons is in a two-year, guaranteed-transfer program. He plans to go to Virginia Tech. But individual benefits accrue, too. In the back of the Goodwill Industries operations center in Hampton, Jerry Hemenway, a trades navigator for TNCC, teaches students skills that will help them enter the workforce.

But individual benefits accrue, too. In the back of the Goodwill Industries operations center in Hampton, Jerry Hemenway, a trades navigator for TNCC, teaches students skills that will help them enter the workforce.