University of Richmond sophomore Jajsani Roane has always been passionate about art and science.

When she graduated from the Henrico High School Center for the Arts outside Richmond, she had the opportunity to go to a large research university or an art school.

“It was tough making a decision between the two, but Richmond kind of fell between them,” she says. “I knew I would be getting an academically rigorous curriculum, but I was also able to pursue my interest and passion in art.”

With a double major in art and environmental science, Roane already is steeped in both fields. Last summer, she was awarded a research fellowship allowing her to work in the lab with a biology professor studying applications of Agrobacterium tumefaciens, which causes crown gall disease in plants.

In January, she joined other students, faculty and alumni in downtown Richmond for an intensive two-day session called Arts in the Life of a City. The program was part of Arts & Sciences NEXT, a program that uses case studies on a variety of topics that help students explore contemporary issues in ways that show how their education might translate to a career.

Roane, whose art focuses on mixed media and illustration, says her team became so enthusiastic about its proposal for how to use art to enrich “the entire population, rather than just an arts district,” that she hopes it might be considered by city leaders.

Losing ground

Nationally, liberal-arts studies are losing ground to programs that tie degrees more directly to jobs at graduation, a consequence of rising college costs and student debt.

So many programs have been cut that the Association of American Colleges & Universities and the American Association of University Professors issued a joint warning last year about the threat to courses once universally viewed as central to the intellectual life of academia.

“We are fighting the good fight,” says Anthony Russell, associate professor of English and coordinator of the Italian Studies Program at UR. He chaired a committee on creativity, innovation and entrepreneurship that proposed collaborative courses and projects for students and faculty across disciplines to work on real-world problems.

The value that students gain from the liberal arts, he says, is the ability to interpret and write critically about complex issues. Students learn problem-solving skills that are important for today’s workforce, he says.

That’s not always clear to the public, he says. “Because liberal-arts colleges cost so much, parents want to see more tangible, quantifiable skills in their student when they graduate.”

Tuition alone at UR in the 2019-20 academic year will be $54,690. The estimated cost of attendance, including tuition, books, room and meals, will be $69,750.

Promise to Virginia

The university’s endowment — thanks to a $50 million gift from Richmond business leader E. Claiborne Robins in 1969 when the institution was struggling to survive — was valued at more than $2.5 billion as of June 30.

That financial underpinning has allowed the university to be one of the few in the nation with a “need-blind” admission policy. The term refers to schools that do not consider an applicant’s financial situation in deciding admission. The university’s total enrollment this year is more than 4,000, with 80 percent of undergraduates coming from outside Virginia.

To make the school more accessible to middle-income students, UR awards full scholarships to Virginians with parental income of $60,000 or less. For the current school year, 30 first-year students received the scholarships, with 103 recipients overall in the entire student body.

Since the income threshold was raised from $40,000 to $60,000 for fall 2014, the program, known as Richmond’s Promise to Virginia, has made 422 awards, including recurring scholarships to students who continue to study at the university, according to Cynthia Price, director of media and public relations.

Preparing for work

Price points to an array of programs designed to prepare students for the work world, such as the Queally Center, which integrates career services with the offices of admission and financial aid.

Price points to an array of programs designed to prepare students for the work world, such as the Queally Center, which integrates career services with the offices of admission and financial aid.

The center also focuses on “employer development” services, such as facilitating employment interviews for graduating students and implementing internship programs.

In 2015, the university started a program guaranteeing each student up to $4,000 to help pay for summer research and internship opportunities. An average of 575 students have been awarded funding each year.

Other programs include Spider Shadowing, which allows students to learn from UR alumni about various career paths; Q-Camp, which introduces business-school students to practical exercises in professional skills; and the Jepson Edge Institute, which offers interactive sessions for leadership-studies students with alumni.

Russell, who was the faculty facilitator for the NEXT program’s arts in the city sequence, says the university is taking steps to clarify the practical connections between the study of liberal arts and the real world.

For Roane, that connection already has been made.

The liberal arts, she says, expose students to a wide variety of topics. That exposure is especially helpful for those who come into college not knowing what they want to study.

They can explore options, find their passions and get direction on how to pursue their goals, she says. They are more competitive in job interviews because they “are a more interesting, more well-rounded person” and “know a lot of approaches to solving problems.”

With the evolving economy, Roane says, “it’s very important to have a wide range of skills. People are basically making their own jobs and making their own place for themselves in the industry.”

For Lauren Higgins, a third-year student from Midlothian, the decision represents an “incredibly encouraging” step toward making U.Va. more diverse.

For Lauren Higgins, a third-year student from Midlothian, the decision represents an “incredibly encouraging” step toward making U.Va. more diverse. Meanwhile in Charlottesville, a $394 million renovation and expansion of the university hospital is underway. The project will add 440,000 square feet and renovate another 95,000 square feet.

Meanwhile in Charlottesville, a $394 million renovation and expansion of the university hospital is underway. The project will add 440,000 square feet and renovate another 95,000 square feet. Kevin Covert, an assistant theater professor who grew up in Winchester, was startled by what he found at Shenandoah when he returned to his hometown after a career on Broadway.

Kevin Covert, an assistant theater professor who grew up in Winchester, was startled by what he found at Shenandoah when he returned to his hometown after a career on Broadway. Nonetheless, it took about a semester for Shenandoah’s amenities and opportunities to take hold for James Turner, a junior from Manassas who is president of the Student Government Association.

Nonetheless, it took about a semester for Shenandoah’s amenities and opportunities to take hold for James Turner, a junior from Manassas who is president of the Student Government Association. The university is announcing this afternoon in Winchester that it will offer bachelor of arts and science degrees in virtual reality design and a bachelor’s of science in esports, or video game competition.

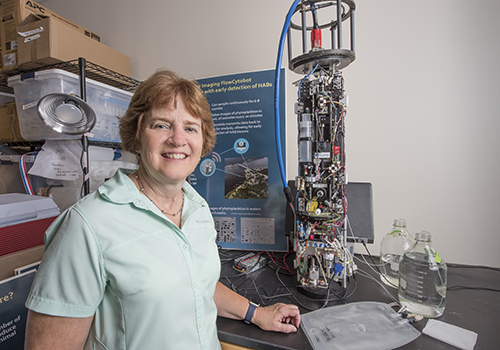

The university is announcing this afternoon in Winchester that it will offer bachelor of arts and science degrees in virtual reality design and a bachelor’s of science in esports, or video game competition. Researchers are working to combat potentially harmful algal blooms, or HABs, that cause red tides. The research includes the use of a new technology known as Imaging FlowCytobot. The submersible instrument can identify individual algal cells in real time, potentially giving hatcheries and nurseries enough notice to get their shellfish out of harm’s way.

Researchers are working to combat potentially harmful algal blooms, or HABs, that cause red tides. The research includes the use of a new technology known as Imaging FlowCytobot. The submersible instrument can identify individual algal cells in real time, potentially giving hatcheries and nurseries enough notice to get their shellfish out of harm’s way. Mark Luckenbach, associate dean of research and advisory services, points to the establishment of the clam and oyster industries as major accomplishments for VIMS. “The big, booming success story is the decades of work we’ve done in the shellfish aquaculture industry,” he says.

Mark Luckenbach, associate dean of research and advisory services, points to the establishment of the clam and oyster industries as major accomplishments for VIMS. “The big, booming success story is the decades of work we’ve done in the shellfish aquaculture industry,” he says. The state also financed a new $10 million, 93-foot research vessel for VIMS. The R/V Virginia was completed over the summer in Canada. It wasn’t made in Virginia, Wells says, because it was too small for the military ship builders and too large for yacht makers.

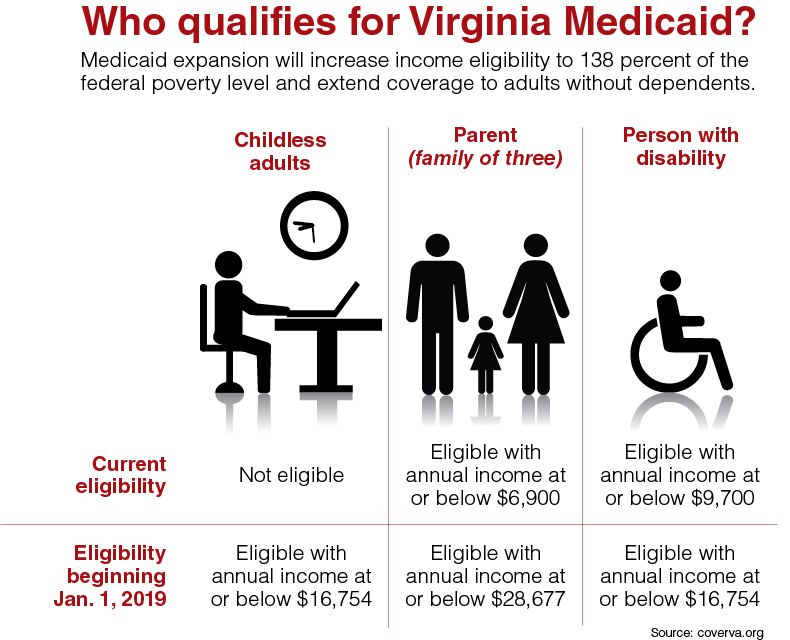

The state also financed a new $10 million, 93-foot research vessel for VIMS. The R/V Virginia was completed over the summer in Canada. It wasn’t made in Virginia, Wells says, because it was too small for the military ship builders and too large for yacht makers. Medicaid expansion in Virginia under the Affordable Care Act has been a slow and contentious process, long-thwarted by state lawmakers who saw it as a break from the commonwealth’s conservative fiscal policies.

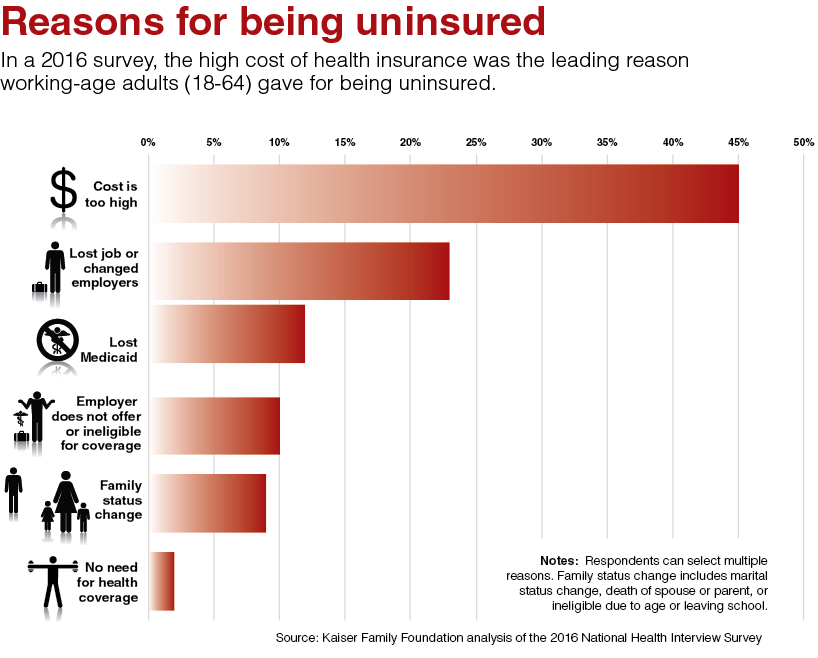

Medicaid expansion in Virginia under the Affordable Care Act has been a slow and contentious process, long-thwarted by state lawmakers who saw it as a break from the commonwealth’s conservative fiscal policies.  Uninsured people, she notes, often put off seeing a doctor or taking medications until they have a medical crisis. Then they end up in emergency rooms and are unable to pay for costly treatments. “Someone still pays that bill,” she says, “and those costs are absorbed by the system and increase costs for everybody else.”

Uninsured people, she notes, often put off seeing a doctor or taking medications until they have a medical crisis. Then they end up in emergency rooms and are unable to pay for costly treatments. “Someone still pays that bill,” she says, “and those costs are absorbed by the system and increase costs for everybody else.” Whether they’re seeking an academic degree or a workforce credential, the students are being prepared for whatever’s next, says Edward “Ted” Raspiller, JTCC president since August 2013.

Whether they’re seeking an academic degree or a workforce credential, the students are being prepared for whatever’s next, says Edward “Ted” Raspiller, JTCC president since August 2013. The alliance offers shorter-term, intensive job training to move adults more quickly into positions that don’t require a degree, says Elizabeth Creamer, vice president of workforce development and credential attainment.

The alliance offers shorter-term, intensive job training to move adults more quickly into positions that don’t require a degree, says Elizabeth Creamer, vice president of workforce development and credential attainment. Frank M. “Rusty” Conner III, the rector of U.Va.’s board of visitors, says he urged Ryan to work “very diligently” to have his leadership team in place where possible when Sullivan’s term ends July 31.

Frank M. “Rusty” Conner III, the rector of U.Va.’s board of visitors, says he urged Ryan to work “very diligently” to have his leadership team in place where possible when Sullivan’s term ends July 31. Capital campaign

Capital campaign Jeffries says the mood on Grounds about Ryan is upbeat. “He’s an impressive guy, and so far, I think he’s made a terrific impression on the people here in Charlottesville. In time he’ll have the opportunity to make a terrific impression on our alumni everywhere.”

Jeffries says the mood on Grounds about Ryan is upbeat. “He’s an impressive guy, and so far, I think he’s made a terrific impression on the people here in Charlottesville. In time he’ll have the opportunity to make a terrific impression on our alumni everywhere.” Students use a 45-foot research vessel, co-owned with the Virginia Aquarium & Marine Science Center, to gather specimens for experiments at the 44,000-square-foot Greer Environmental Sciences Center, which opened last fall.

Students use a 45-foot research vessel, co-owned with the Virginia Aquarium & Marine Science Center, to gather specimens for experiments at the 44,000-square-foot Greer Environmental Sciences Center, which opened last fall.