The Virginia Beach home of Macon and Joan Brock is filled with art, but one piece stands out. A revolving, geometrical glass sculpture by artist Jon Kuhn sparkles like a diamond as it refracts light from a window. The sculpture’s steady, swirling motion is the result of its perfect balance on a pointed base.

Joan Brock says she feels a special connection to the sculpture. That would not surprise people who know the Brocks. The art’s focus and balance are an apt reflection of their approach to philanthropy.

Joan Brock says she feels a special connection to the sculpture. That would not surprise people who know the Brocks. The art’s focus and balance are an apt reflection of their approach to philanthropy.

Macon is the chairman, co-founder and former CEO of Chesapeake-based discount retailer Dollar Tree Inc. As the company has grown over the past 31 years to become a Fortune 500 corporation, the Brocks have given millions of dollars to charitable causes.

But despite their wealth, the Brocks remain down-to-earth. “They are the most unassuming, grounded people you would want to meet,” says John “Dubby” Wynne, the retired president and CEO of Landmark Communications, who serves with Macon on the Hampton Roads Community Foundation Board.

The couple’s donations have included gifts to charitable causes in the visual arts, the environment and education, all areas that reflect their passions. Many of their gifts go to nonprofits in Virginia, but they also have given money to build a school in Sierra Leone.

The Brocks are involved in the organizations they support, and they believe in transparency and good governance. “When we do philanthropy, we want to know what’s going on with it,” Joan says. “We want to know it’s financially well managed overall. That’s a trend we follow.”

That guiding philosophy is one of the reasons the Association of Fundraising Professionals chose the couple as the nation’s Outstanding Philanthropists in 2015.

“They were frankly one of the easier candidates we have chosen,” says Michael Nilsen, vice president of communications and public policy for the Arlington-based association. “It was a slam-dunk choice. They are the epitome of what you want an outstanding philanthropist to be.”

The Brocks were “blown away” by the award, Joan says. “A lot of people from the [Hampton Roads] community came to New York to see that happen.”

Love for the bay

One of the causes that the Brocks support is the work of the Chesapeake Bay Foundation. The couple gave $3.5 million to help build the foundation’s Brock Environmental Center in Virginia Beach. The center, opened in 2014, has met some of the strictest building standards in the world for sustainability. It produces more energy than it consumes and is the first commercial building to be permitted to treat rainwater for drinking water. The center serves as the foundation’s Hampton Roads office and the hub for its education programs.

One of the causes that the Brocks support is the work of the Chesapeake Bay Foundation. The couple gave $3.5 million to help build the foundation’s Brock Environmental Center in Virginia Beach. The center, opened in 2014, has met some of the strictest building standards in the world for sustainability. It produces more energy than it consumes and is the first commercial building to be permitted to treat rainwater for drinking water. The center serves as the foundation’s Hampton Roads office and the hub for its education programs.

“We love the Chesapeake Bay and what it stands for,” Macon says. “The center stands as a symbol for purity and all that can be accomplished with environmental building standards.”

William C. Baker, president of the Chesapeake Bay Foundation, remembers the moment he received a call from Macon confirming the couple’s plan to make the donation for the center. “I was walking on the sidewalk in Washington, D.C., and I nearly fell on my face,” Baker says.

He later asked the Brocks why they made the gift. “Joan said, ‘Macon and I wanted our children and grandchildren to know how important the environment is to us.’ That spoke volumes,” Baker says.

The Brocks are “all business” when it comes to donating money, he adds, suggesting their support sets a gold standard for charitable causes. “When the Brocks say ‘yes,’ it tells the public and other potential donors that it’s serious, successful and worth supporting.”

The couple also supports the Virginia Aquarium & Marine Science Center in Virginia Beach. “They are helping us educate people about the marine environment,” says Lynn Clements, the center’s executive director.

The Brocks likewise are longtime supporters of the Chrysler Museum in Norfolk. Joan was the first woman to chair the museum’s board of trustees. The museum’s main building, dedicated in 2014, is named in honor of the couple.

The visual arts are all about creativity, Joan says. “When people move into a community, the arts are the first thing they point to.”

Support for alma maters

The Brocks have donated generously to their alma maters — Randolph-Macon College in Ashland and Longwood University in Farmville. Last year they gave $5.9 million to Longwood to endow the Brock Endowment for Transformational Learning, furthering the university’s mission to educate citizen leaders. Their donations also helped build Brock Commons in 2000, turning a street into a pedestrian area with fountains and sculptures.

“If it wasn’t for Brock Commons, Longwood wouldn’t have been able to host the Vice Presidential Debate last fall,” says W. Taylor Reveley IV, the university’s president. The October matchup between U.S. Sen. Tim Kaine of Virginia and then-Gov. Mike Pence of Indiana drew national attention to the school. The Brocks “have profoundly enriched the student experience here at Longwood,” Reveley says.

The same is true for Randolph-Macon. “They have had an imprint on a number of building projects,” says Robert R. Lindgren, the college’s president. “They were major contributors to the new science building that is going up and will be finished this summer. They are two really great people.”

Macon likes to use the phrase “you want to move the needle” in explaining his relationship with the college. “I can make a difference there, and so I chose to do that,” he says. “You get more back when you give.”

To honor Macon’s father, a physician, the couple donated money to Eastern Virginia Medical School in Norfolk to help create the M. Foscue Brock Institute for Community and Global Health. “They had a desire to continue Macon’s father’s good work in helping Hampton Roads be a healthier community,” says Dr. Cynthia Romero, the institute’s director.

Their donation allowed the institute to start a Spanish medical curriculum for students learning how to care for Hispanic patients.

Health has been on the minds of the Brocks ever since Macon was diagnosed with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF), a scarring of the lungs that makes it difficult to take a deep breath.

He had a double-lung transplant at Cleveland Clinic in September 2014. Two years later the couple helped establish the Macon and Joan Brock Endowed Chair at Cleveland Clinic’s Respiratory Institute.

Growing up in Norfolk

The Brocks’ penchant for philanthropy stems from their upbringing, which was comfortable, not rich or poor. “We grew up with community service and giving back to the community,” Joan says.

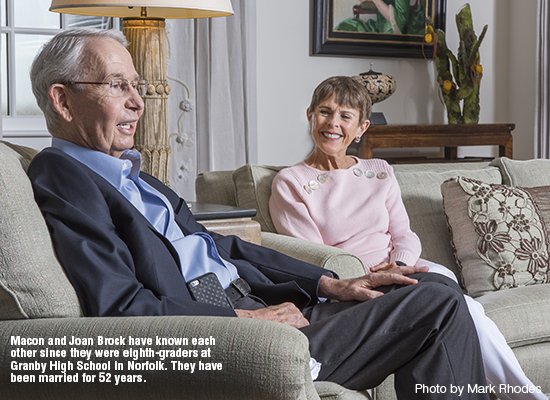

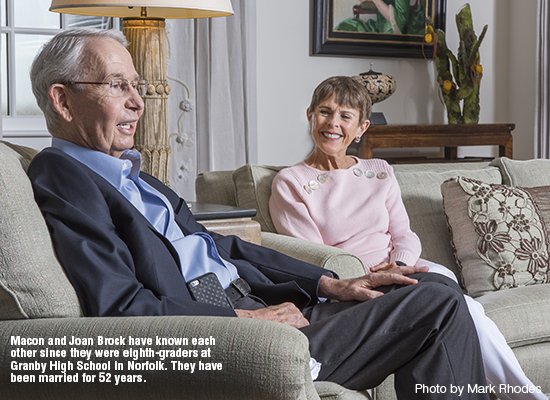

The Brocks, who have been married 52 years, grew up in Norfolk. They met in 1955 as eighth-graders at Granby High School. At the time, Macon was dating Joan’s friend, Judy Melchor. Joan (then Joan Perry) liked Macon, but he didn’t show an interest in her until Judy broke up with him. “I was the aggressor,” Joan says, shooting her husband a grin during an interview.

The Brocks, who have been married 52 years, grew up in Norfolk. They met in 1955 as eighth-graders at Granby High School. At the time, Macon was dating Joan’s friend, Judy Melchor. Joan (then Joan Perry) liked Macon, but he didn’t show an interest in her until Judy broke up with him. “I was the aggressor,” Joan says, shooting her husband a grin during an interview.

The two began dating seriously when they were in college — Macon at Randolph-Macon, majoring in Latin, and Joan at Longwood, majoring in mathematics. He proposed in spring 1964, and they married later that year.

“Of all the things I’ve done in my life, proposing to Joan was the best,” Macon recounted in “One Buck at a Time,” a memoir released this year that chronicles the growth of Dollar Tree.

After serving as a captain in the U.S. Marine Corps with service in Vietnam, Macon was employed by the Office of Naval Intelligence before going to work for Joan’s father, K.R. Perry, at his variety store in Norfolk’s Wards Corner shopping district. Opened as a Ben Franklin franchise in 1953, the store later was renamed K&K 5&10. Macon and Doug Perry, Joan’s brother, ran the store.

K&K Toys and Dollar Tree

In 1970, Macon, Doug Perry and K.R. Perry started K&K Toys, a chain that eventually grew to more than 130 stores on the East Coast. The business was sold to KB Toys in 1991.

In 1986, Macon, Doug Perry and Ray Compton started Dollar Tree, then known as Only $1.00. “Doug was traveling when he sees this dollar business,” Macon says. “He came back to the office, and I was in Hong Kong, and he said to Ray, ‘Let’s do this.’ We kicked the idea around and said let’s try it. We modeled it after our approach to the variety business where merchandise was based on value.”

The goal was to evoke an “I-can’t-believe-this-is-just-a-dollar” response from shoppers. “That’s what we built on — surprising customers,” Macon says. “We were looking for shock and awe.”

The company opened stores across the country. “We hardly put a store anywhere it wasn’t accepted,” Macon says.

But, as with any good idea, a number of other competitors entered the dollar-store space.

“Over the years we rolled them up and bought them to expand our business,” Macon says. “We acquired companies and took those people in with their know-how. We wanted to see what they were doing right that we didn’t know about yet. We gained knowledge every time we acquired someone else.”

In 2015, Dollar Tree completed its biggest deal, acquiring Family Dollar Stores for $9.1 billion, a move that increased its total number of stores from 5,800 to more than 14,000. Family Dollar serves mostly urban, lower-income markets, while Dollar Tree is aimed at suburban, middle-income customers.

“Diversifying makes sense,” Macon says of the Family Dollar acquisition. “We were able to buy it at a reasonable price. So far it’s going well. The idea is to improve Family Dollar customer experience.”

Leadership lessons

Macon, Perry and Compton worked as a team in all of their endeavors, a point emphasized in Macon’s memoir. “No one person does everything alone. It takes a team,” Macon says. “Ray was our financial leader. Doug ended up managing our real estate and locations, getting stores built. I was the merchant, buyer and marketing and store operations manager. My strength was that I was a good merchant. I had a knack for buying and choosing the merchandise.”

Macon learned the importance of teamwork in the Marines. “It clearly had a big effect on me. It gives you maturity real quick,” he says of the military.

He learned that, as a Marine officer in a combat situation, decision-making is pushed down in “the organization as you can,” he says, adding that a leader has to trust people and catch them doing something right. “These are principles the Marine Corps holds dear.”

Leadership is one of Macon’s biggest strengths, says Compton, now retired and living in Williamsburg after serving as executive vice president and chief financial officer of Dollar Tree.

“The best way I could describe Macon is: He was always a leader, regardless of the situation. Macon always allowed people to do what they were capable of. He was always one of the first to recognize not what they were doing wrong but what they were doing right, and he would exemplify that.”

Macon’s drive to excel took hold early in his life. “If I was going to do something, I wanted to be good at it,” he says. “I never thought I would be this high up the chain. It wasn’t my goal to get rich. It just happens that, if you do well, good things follow.”

Wynne, the retired Landmark executive, refers to Macon as “one of the best entrepreneurs this community has produced … He is a creative, innovative guy. What he did at Dollar Tree is unbelievable.”

Macon doesn’t just join boards, Wynne adds. “He gets on boards that he is interested in and can make a difference. One of the things about Macon is: He isn’t afraid to say what he thinks. He’s not afraid to be a contrarian. He doesn’t go with the flow if he believes there is a better answer.”

‘Money is a burden’

The Brocks endorse “The Giving Pledge,” an initiative started by billionaires Warren Buffett and Bill Gates urging wealthy people to give most of their fortune to philanthropy.

“I highly admire Warren Buffett. What a man,” Macon says. “He’s going to give it away and change the world.”

“I think he made people stop and think about philanthropy and their legacies,” Joan adds.

The fact that a person has money is a plus, but it’s “not the answer,” says Macon. “Money is a burden, a responsibility. You have to be good stewards.”

With that thought in mind, the Brocks have started a family foundation, the Brock Foundation. It gives the Brocks’ three adult children the opportunity to donate to their chosen charities. “It’s a smarter way to give money,” Joan says. “We give each child a certain allocation. We ask them to be involved in what they do and to make their own decisions.”

In looking at their lives, Macon and Joan Brock want people to think of them as team players.

“We want them to say, ‘They were good people that did well and that did the right thing,’” Macon says. “I’ve had some time to think about that recently. You want to be good and work hard.”

Joan Brock says she feels a special connection to the sculpture. That would not surprise people who know the Brocks. The art’s focus and balance are an apt reflection of their approach to philanthropy.

Joan Brock says she feels a special connection to the sculpture. That would not surprise people who know the Brocks. The art’s focus and balance are an apt reflection of their approach to philanthropy. One of the causes that the Brocks support is the work of the Chesapeake Bay Foundation. The couple gave $3.5 million to help build the foundation’s Brock Environmental Center in Virginia Beach. The center, opened in 2014, has met some of the strictest building standards in the world for sustainability. It produces more energy than it consumes and is the first commercial building to be permitted to treat rainwater for drinking water. The center serves as the foundation’s Hampton Roads office and the hub for its education programs.

One of the causes that the Brocks support is the work of the Chesapeake Bay Foundation. The couple gave $3.5 million to help build the foundation’s Brock Environmental Center in Virginia Beach. The center, opened in 2014, has met some of the strictest building standards in the world for sustainability. It produces more energy than it consumes and is the first commercial building to be permitted to treat rainwater for drinking water. The center serves as the foundation’s Hampton Roads office and the hub for its education programs.  The Brocks, who have been married 52 years, grew up in Norfolk. They met in 1955 as eighth-graders at Granby High School. At the time, Macon was dating Joan’s friend, Judy Melchor. Joan (then Joan Perry) liked Macon, but he didn’t show an interest in her until Judy broke up with him. “I was the aggressor,” Joan says, shooting her husband a grin during an interview.

The Brocks, who have been married 52 years, grew up in Norfolk. They met in 1955 as eighth-graders at Granby High School. At the time, Macon was dating Joan’s friend, Judy Melchor. Joan (then Joan Perry) liked Macon, but he didn’t show an interest in her until Judy broke up with him. “I was the aggressor,” Joan says, shooting her husband a grin during an interview.

Kevin O’Connor has had a passion for brewing beer since making his first batch in college. In 2009, he turned that hobby into a business, founding O’Connor Brewing Co. in Norfolk.

Kevin O’Connor has had a passion for brewing beer since making his first batch in college. In 2009, he turned that hobby into a business, founding O’Connor Brewing Co. in Norfolk.