When the next history of the Richmond region is written, the author may look back on these times as its golden era for development. Driving that change has been the unprecedented arrival of millennials, the members of America’s largest generation.

It’s all in the numbers, says Basil Hallberg, a financial analyst at the Richmond-based commercial real estate firm Cushman & Wakefield |Thalhimer.

“As of May 2017, the region has had 81 consecutive months of year-over-year employment growth,” Hallberg says. “Since 2004, the population in Richmond started growing at a pace that is unprecedented at least since the ‘70s. The 2004 timeline correlates with the first wave of millennials leaving the nest.”

Time magazine recently ranked Richmond second among U.S. cities with the highest rate of millennial growth from 2010 to 2015, with an upsurge of 14.9 percent. (Virginia Beach was first on the list at 16.4 percent.)

Millennials have made a visible impact on the city of Richmond, transforming its downtown into a youth-driven marketplace of loft apartments, shops, restaurants and craft breweries. The city also has become a venue for athletics in many forms, including running (annual marathon and 10-K races), cycling (UCI Road World Championships held in 2015) and kayaking (Class IV rapids in the James River).

As if to accent its reputation as a millennial magnet, the city has a new mayor, Levar Stoney, who is 36.

But will urban-centric single millennials choose to live in the city once they marry, buy homes and begin families?

Affordability counts

Citing Virginia Employment Commission figures, Thalhimer’s Hallberg notes that, the number of establishments in (mostly businesses) in the city increased by 10.4 percent from 2010 to 2016.

Moreover, since the beginning of 2016, the arrival of new companies and the expansion of existing companies in the city have added 1,400 jobs.

Making the biggest splash is CoStar Group, a major Washington, D.C.-based real estate data firm. In October, it announced plans to establish a research center employing more than 730 workers in downtown Richmond near the James River.

Many executives who have brought companies to the Richmond area have cited its affordability for their employees. Thalhimer reports that the cost of living in the Richmond metro area is 5 percent below the national average, and housing costs are 11 percent below the national average.

Those factors have helped the region retain a well-educated workforce, a major attraction for new employers. In the Richmond area, more than 30 percent of adults age 25 or older have college degrees, and 60 percent of working adults have some college experience.

Navy veteran finds a home

Aaron Metrick, 33, is one of the millennials who has flocked to the region. “We did a national search of where we wanted to live… and we picked Richmond, and then we tried to find a job,” says Metrick, a nine-year Navy veteran from Annapolis, Md. At the beginning of 2015, Metrick and his wife, Kathy, moved to the area with their two small children.

Metrick, now a vice president at Bank of America, says he was attracted by the region’s surging economy, well-regarded local employers and lower housing costs.

But perhaps the most important factor for the Metricks were the intangibles. They believe the Richmond area offers big-city amenities without the hassles.

“We have access to stores, but without the headaches of D.C. traffic and high expenses,” he says.

Metrick says Richmond’s geographic position — a couple of hours each way from the mountains and the beach — also makes it a good spot for quick weekend getaways.

Area parks and access to the James River are added attractions for the Metricks. “We go the river just about every weekend,” he says.

Concerns about schools

While the Metricks are big fans of downtown Richmond, they don’t live in the city. Instead, their home is in suburban Chesterfield County. “We did research on the schools, and they seemed better outside the city,” Aaron Metrick says.

That assessment points to a nagging question that has accompanied the surge of millennials: Will the struggles of Richmond Public Schools make young couples hesitant to settle in the city when they have children?

Only 17 of Richmond’s 44 schools currently are fully accredited. Eleven of those 17 are elementary schools. Statewide, 81 percent of public schools are fully accredited.

In mid-August, the Richmond City School Board and the Virginia Board of Education were putting the final touches on a memorandum of understanding aimed at moving city schools toward full accreditation. The Virginia Department of Education will announce new accreditation ratings for all public schools in mid-September.

Meanwhile, the city’s debt capacity is maxed out through at least 2021, restricting its ability to renovate or replace Richmond school buildings needing millions of dollars of repair.

A Circuit Court judge has ordered that a proposed change in the city charter addressing the funding issue appear on the November ballot in Richmond, according to the Richmond Times-Dispatch. The judge’s decision came in response to a petition signed by more than 10,000 city voters.

If voters approve the charter change and it is passed by the General Assembly, the mayor would be required, within six months, to develop a funding plan for school facilities without a tax increase. The measure would require Stoney to inform city council if he is unable to develop such a plan.

While Metrick and his wife chose to live in the suburbs, he notes that many friends and colleagues living in the city appear pleased with the elementary school education their children are getting. But, he says, some of these parents are not sure what choices they will make for middle school.

One parent with a child in the Richmond school system is Jenny Tremblay West, a private contractor. She and her husband, who works for the city, have two young sons and live in the city’s Church Hill area. One son is entering first grade at Chimborazo Elementary after attending city preschool and kindergarten programs. The other son is not yet in preschool.

“We’ve had an extremely positive experience,” she says. “We’ve lucked out with really great teachers.” But, she adds, many parents in her neighborhood have opted to send their children to private schools or Patrick Henry School of Science and Arts, an elementary charter school that selects pupils in a lottery.

“Richmond has attracted so many younger folks,” West says. “But it’s going to take every person, pushing hard, to make [the school system] better. I’m very hopeful.”

School system officials did not respond to requests for comment.

An April report by the Greater Richmond Partnership, an economic development group, found that enrollment in Richmond schools has been growing.

Between the 2011-12 and 2016-17 school years, “enrollment at the city’s schools increased by 1,532 students, with 89 percent of this increase, or 1,357 students, being at the elementary school level,” the report says.

Questions about where millennials ultimately will settle aren’t confined to the Richmond area. Several national studies have shown that many millennials want to buy homes but are putting off the decision longer than their parents did.

“The median age of a first-time home buyer is 33 years old, compared to 29 a generation ago,” according to the Zillow Group Report on Consumer Housing Trends, which found that half of millennial home buyers live in the suburbs while 30 percent live in cities.

Building boom

The GRP report notes that from 2010 to 2016, 12,817 new residents moved into the city, bringing its estimated population to 223,170.

The report also says that households with incomes of $75,000 to $150,000 in the city increased by 40 percent during the six-year period, and the number of residents with bachelor’s degrees rose by 25 percent.

A flood of new housing has accompanied the city’s population growth. Between 2009 and 2015, the latest year available, the partnership says the number of housing units — including apartments, townhouses and single-family homes —increased by 5,318.

“There’s a tremendous influx of people moving to the city, and it’s something you can see across the city’s skyline. Cranes and new buildings are being erected to keep up with the increase of families,” Chuck Peterson, vice president of business information at the partnership, said in remarks accompanying the report.

Colliers International, a global commercial real estate services firm, says that there are about 3,000 new apartment units in “lease up” — the time period for a newly available property to attract tenants and reach stabilized occupancy — and an additional 4,800 new apartments are in some stage of construction.

The firm estimated that the Richmond region would add 10,800 jobs this year and well over 12,600 next year.

According to Colliers, the entire Richmond region, which it defines as 16 localities, grew by 190,000 residents between 2000 and 2013 and is forecast to grow by an additional 852,000 between 2012 and 2030. “Out of the top 10 absolute growth markets in the U.S., Richmond was forecasted as the highest growth rate (68.4 percent) followed by Atlanta (45.6 percent) and San Antonio (36 percent),” Colliers says.

Andrew Florance, the founder and CEO of CoStar, already sees much more room for growth in the regional housing market. At an annual Downtown Development Forum in April, Florance identified a shortage of 20,000 housing units in the Richmond region, with only six new residential units for every 10 new households.

As the region’s population grows, an effort is underway to transport people through the city of Richmond more efficiently. A 7.6-mile bus rapid-transit system, called The Pulse, will travel between Richmond’s east and west ends. The idea is to provide the advantages of a rail transit system without the cost.

As the region’s population grows, an effort is underway to transport people through the city of Richmond more efficiently. A 7.6-mile bus rapid-transit system, called The Pulse, will travel between Richmond’s east and west ends. The idea is to provide the advantages of a rail transit system without the cost.

“It’s the first piece of high-quality, reliable, rapid-transit service that will pave the way for what we envision will become a world-class, regional transit system,” says David Green, CEO of GRTC, the city’s transit system.

Boost in tourism

As more people have moved to the Richmond area for jobs, there also has been a surge in the region’s tourism. “Richmond is on fire,” says Jack Berry, president and CEO of Richmond Region Tourism.

Berry notes that the area has been setting tourism records for the past three years, based on hotel occupancy and hotel tax records. “You can’t find a hotel room on Saturday night,” he says.

History once was the biggest draw for Richmond tourism. Now, Berry says, it’s food and craft beer. “Two years ago, National Geographic said two cities to visit for food were New Orleans and Richmond. We’ve become the food destination,” he says.

California-based Stone Brewing Co., the nation’s 10th-largest craft brewer, has its East Coast brewery in Richmond. The region also is home to a growing list of local craft breweries and cideries, now numbering about 30.

Growing logistics center

The Richmond region also continues to burnish its image of a logistics center.

Seattle-based retail giant Amazon has leased a 328,000-square-foot building in Hanover County as a package sorting facility employing 300 people. It is expected to open in September.

Amazon already operates massive fulfillment centers in Chesterfield and Dinwiddie counties.

Also, Newport Beach, Calif.-based Panattoni Development Co. has bought 62 acres in the city near Richmond Marine Terminal for a 1 million-square-foot distribution center.

25-year turnaround

Lucy Meade, director of marketing and development for downtown promotion group Venture Richmond, says recent developments in the city have been in the making for decades.

Lucy Meade, director of marketing and development for downtown promotion group Venture Richmond, says recent developments in the city have been in the making for decades.

“A handful of people had a vision that we couldn’t let downtown go down. We had to figure out a way to turn it around,” she says.

Meade recalls the 1990s when the city’s crime rate climbed and many of its major downtown stores closed. Richmond’s population declined by more than 20 percent from 1970 to the early 2000s.

In those days, Meade says, people promoting the city were happy with even minor progress, when, for example, artists began filling empty downtown buildings because of their cheap rent.

In time, developers and preservation groups joined forces to take advantage of historic tax credits and other incentives to revitalize old buildings.

Today, Meade says, the city has an unmistakable vibrancy. “There has been this cumulative effect, sort of like compound interest,” she says. “Sometimes, it takes 25 years to turn an urban area into an overnight success.”

Meade expects millennials to continue coming downtown no matter what part of the Richmond region they choose to live.

“We love seeing young people getting married and settling down in one of the city’s cool neighborhoods and definitely want to see continued growth in this area,” she says. “But we are realistic and know that some young families will want to raise their children in the suburbs.”

Burke Estes, the starting quarterback on Randolph-Macon College’s football team and a presidential scholar, described the defining difference between going to a large state university and attending the Ashland school.

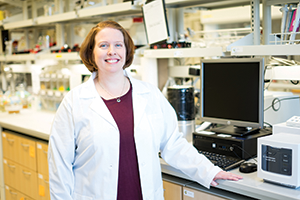

Burke Estes, the starting quarterback on Randolph-Macon College’s football team and a presidential scholar, described the defining difference between going to a large state university and attending the Ashland school. It’s also been a a successful time for chemistry professor April Marchetti, R-MC ’97. In 2015, she led a team that won the largest grant ever received by the college, nearly $1.2 million from the National Science Foundation, to establish a program to train STEM (science, technology, engineering and mathematics) teachers for high-need local school districts.

It’s also been a a successful time for chemistry professor April Marchetti, R-MC ’97. In 2015, she led a team that won the largest grant ever received by the college, nearly $1.2 million from the National Science Foundation, to establish a program to train STEM (science, technology, engineering and mathematics) teachers for high-need local school districts. Sally Selden, the college’s vice president and dean for academic affairs, says creating more graduate programs and recruiting more graduate students in areas that serve the region — such as health sciences — are important initiatives in the Vision 2020 plan.

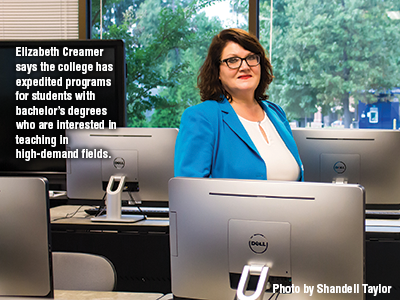

Sally Selden, the college’s vice president and dean for academic affairs, says creating more graduate programs and recruiting more graduate students in areas that serve the region — such as health sciences — are important initiatives in the Vision 2020 plan. Later, Rhodes said that, while he was not offering excuses for the drop in enrollment, the dynamics under which community colleges operate explain a lot about what happened.

Later, Rhodes said that, while he was not offering excuses for the drop in enrollment, the dynamics under which community colleges operate explain a lot about what happened. While Reynolds has seen an overall drop in enrollment, students have been rushing to enter the college’s workforce development program for high-demand fields, such as welding, manufacturing and health care.

While Reynolds has seen an overall drop in enrollment, students have been rushing to enter the college’s workforce development program for high-demand fields, such as welding, manufacturing and health care.

As the region’s population grows, an effort is underway to transport people through the city of Richmond more efficiently. A 7.6-mile bus rapid-transit system, called The Pulse, will travel between Richmond’s east and west ends. The idea is to provide the advantages of a rail transit system without the cost.

As the region’s population grows, an effort is underway to transport people through the city of Richmond more efficiently. A 7.6-mile bus rapid-transit system, called The Pulse, will travel between Richmond’s east and west ends. The idea is to provide the advantages of a rail transit system without the cost. Lucy Meade, director of marketing and development for downtown promotion group Venture Richmond, says recent developments in the city have been in the making for decades.

Lucy Meade, director of marketing and development for downtown promotion group Venture Richmond, says recent developments in the city have been in the making for decades.

When Gaumer, a certified public accountant, arrived at Emory & Henry in December 2014, he faced a budget crisis, because of what college officials say was an extraordinarily high level of debt service. The college, in fact, faced a budget gap of $3 million in fiscal year 2016-2017.

When Gaumer, a certified public accountant, arrived at Emory & Henry in December 2014, he faced a budget crisis, because of what college officials say was an extraordinarily high level of debt service. The college, in fact, faced a budget gap of $3 million in fiscal year 2016-2017. Matt Lanzer was out of a job in 2003 when his previous employer consolidated its circuit board manufacturing operations in China.

Matt Lanzer was out of a job in 2003 when his previous employer consolidated its circuit board manufacturing operations in China. Anna Lenz knows about that. In Troy, Mich., she oversaw 30 people in the accounting office of Kelly Services, a staffing agency. Lenz moved to the Washington, D.C., area when her husband, Edward, was named general counsel of the American Staffing Association.

Anna Lenz knows about that. In Troy, Mich., she oversaw 30 people in the accounting office of Kelly Services, a staffing agency. Lenz moved to the Washington, D.C., area when her husband, Edward, was named general counsel of the American Staffing Association. “Now, there’s a whole team … a program manager, two coordinators and an operations manager,” says Charlie Palumbo, director of transition and employment programs for Veterans Services.

“Now, there’s a whole team … a program manager, two coordinators and an operations manager,” says Charlie Palumbo, director of transition and employment programs for Veterans Services. Michael Bluemling Jr., an Army vet who is V3’s new program manager, remembers working with a veteran who had been a physician’s assistant in the military. The vet had no way to transfer his skills to a civilian health-care environment. “This is an example of how this program is going to be able to meet that need,” Bluemling says.

Michael Bluemling Jr., an Army vet who is V3’s new program manager, remembers working with a veteran who had been a physician’s assistant in the military. The vet had no way to transfer his skills to a civilian health-care environment. “This is an example of how this program is going to be able to meet that need,” Bluemling says. “Mid-Atlantic Maritime Academy’s V3 story has a few layers to it,” says Capt. Ed Nanartowich, the academy’s president. “V3 promotes the hiring of veterans, and MAMA seeks veterans as a premier human asset in delivering deck and engineering courses to mariners nationwide.”

“Mid-Atlantic Maritime Academy’s V3 story has a few layers to it,” says Capt. Ed Nanartowich, the academy’s president. “V3 promotes the hiring of veterans, and MAMA seeks veterans as a premier human asset in delivering deck and engineering courses to mariners nationwide.”