Christina Fleming embarked upon a career in marketing with the goal of getting an executive MBA degree, but other commitments kept getting in the way.

She got married, had two children and moved up the corporate ladder for 26 years, rising to chief marketing officer at Blackboard Inc., a global education technology company that was based in Reston. In April, she launched her own company, Monarch Performance Marketing.

“It was just something that I kept putting off, but I always knew I wanted to do it,” Fleming says. “So, towards the end of last year, I made the decision to go ahead and pursue my MBA. I really felt it would be important and helpful to me as a business leader.”

She looked at executive MBA programs that were within driving distance of her Laurel, Maryland, home, taught in-person and could be completed in under two years. She chose the one at William & Mary‘s Raymond A. Mason School of Business and enrolled in fall 2021 as one of 13 students in her cohort. Now about halfway through the program, Fleming commutes every other weekend to Williamsburg for classes.

“I was learning every day in the moment and accumulating all sorts of skills [at work], but what the MBA has done is given me an opportunity to really step back and look at how all these aspects of business and the economy are connected,” she says. “It just provides this solid foundation in which I believe I can become a better leader.”

Executive education programs are designed for business professionals like Fleming who have managerial or executive- level experience and want to improve their knowledge and skills so they can advance in their careers. The classes help them stay on top of the latest industry trends, expand their networks and get real-world experience working on projects.

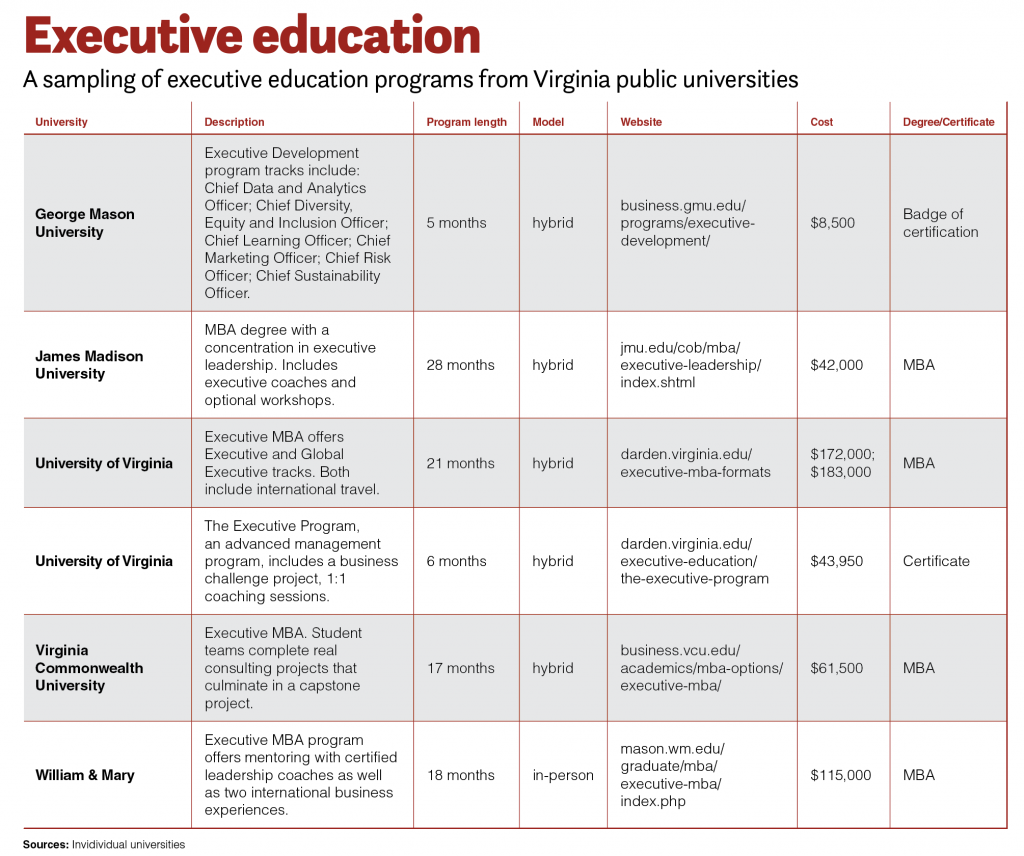

Seven Virginia public universities offer some form of executive education. Programs range from traditional MBA degree programs at W&M, George Mason University, James Madison University, the University of Virginia and Virginia Commonwealth University to shorter certificate programs offered at George Mason University and Virginia Tech. GMU offers customized programs for businesses and organizations, as do U.Va., Virginia Tech and Old Dominion University.

One of the prevailing trends is shorter and more convenient MBA programs, in response to student demand.

William & Mary has offered executive MBA degrees for more than 40 years. Three years ago, the school sought feedback from W&M’s prospective students and alumni — as well as from alumni of other executive education programs across the country and employers, says Ken White, associate dean of W&M’s MBA and executive programs.

What they heard was that students thought MBA programs took too long and that they wanted a certificate option that took less than two years. Respondents also wanted leadership coaching and the possibility of international business experience, White says.

Student feedback helped reshape W&M’s program, which is now 18 months long with eight-hour, in-person classes every other Friday and Saturday.

Global and national perspectives — provided most often by taking students to other countries and introducing them to corporate leaders — are increasingly important, too.

W&M students spend a short residency in Washington, D.C., and go abroad twice to study and meet with business leaders. This year, they’ll go to Greece and South Africa.

“That was another piece that we got in our research,” White says. “People were saying, ‘You know, we need to know a little bit more about the federal government and how it affects business.’ So, we have the two global immersions, and then we have a D.C. residency where the class goes up there for not quite a week.”

William & Mary isn’t alone in offering global travel opportunities to executive MBA students.

George Mason’s MBA Global Residency is a weeklong international study tour. Past residences have included Chile, China, Central Europe and Western Europe.

VCU‘s program includes a roughly 10-day trip abroad, usually to partner universities in Central and South America or Europe. Naomi Boyd, VCU’s business school dean, says faculty look at who’s in a cohort, pick a location and build an agenda that can include projects and case studies.

As part of JMU’s MBA program, students can take an optional 7- to 10-day trip abroad to countries such as China, Portugal, Argentina, Chile, Germany and Vietnam, making visits to companies like Hyundai Motor Co., Maersk or Rémy Martin.

Speeding up

At the University of Virginia’s Darden School of Business, MBA students have two nonresidential executive MBA tracks: the executive and global executive programs. Both take 21 months and are hybrid, with in-person sessions held at Darden’s D.C. Metro space in Rosslyn. The other classes are offered remotely, including live online courses and self-paced activities.

Executive students participate in one international residency with the option of adding others, while global MBA students participate in four residencies outside the United States. These typically include a mix of company visits, talks with industry leaders, meetings with executives and cultural excursions. U.Va. also offers a full-time residential MBA program and a part-time MBA option with more scheduling flexibility.

Students in both U.Va. executive MBA programs also participate in two weeklong leadership residencies in Charlottesville on the Darden grounds.

VCU used to offer a two-year MBA program, but it has now shortened the time to get the degree to 17 months, with classes held on alternating weekends, Boyd says.

James Madison University’s College of Business offers an MBA with an executive leadership concentration over 28 months, a longer period than other universities, but it’s geared toward student accessibility. Most of the classes are held online, with in-person residencies that meet on a Saturday once every other month in Tysons. (JMU’s largest alumni populations are concentrated in the Richmond and D.C. areas.)

“It gives us somewhat of a regional tie for people interested in the program in the D.C. metro area, and then maybe some folks who have connections to the institution who live outside of there can still participate in our program,” says Michael Prior, the MBA program’s director of marketing.

Universities also have started offering even shorter options — typically for executives in pursuit of a certificate instead of a master’s degree.

The University of Richmond, a private university, offers a 14-week “mini-MBA” program, for example.

U.Va. offers The Executive Program, a six-month, hybrid advanced management certificate program that costs about $43,950 — less than a third the cost of the Darden executive MBA tracks, which cost $172,000 to $183,800. Virtual sessions involve a business challenge project, and faculty consultation and one-to-one coaching are included.

George Mason’s School of Business offers a traditional MBA program with accelerated or part-time options, and the school also targets specific specialties, including data and analytics. GMU’s hybrid executive education courses run five weeks each, and students earn a badge of certification. Executive specialties include diversity, equity and inclusion; marketing; risk; and sustainability.

GMU also offers a two-day real estate analytics program, and its faculty can customize offerings for organizations on topics such as government contracting, data analytics and real estate.

Virginia Tech’s Pamplin College of Business in the past has hosted cybersecurity risk series for executives and board members, with special focuses on entrepreneurship and integrated security in event management. Tech currently offers an executive data analytics certificate program.

Old Dominion University doesn’t offer an MBA specifically for executives, but its School of Continuing Education provides customized training for employers who don’t want to put employees “through a full-blown degree,” says Renee Felts, its assistant vice president for academic initiatives and continuing education.

Faculty can create a crash course on anything from soft skills to advances in cybersecurity. Classes can be taught in person, online or via a hybrid of the two. Fees depend on what’s created, and employers may pick up the tab.

“We feel like it’s a well-kept secret,” Felts says.

Executive education doesn’t come cheap, although the payoff can be career advancement and a bigger paycheck. Prices for these programs currently range from $995 for George Mason’s two-day real estate analytics course to $183,000 for U.Va.’s Global Executive MBA. Financial help is often available through the universities or an employer.

Caitlyn Read was associate director for communications at James Madison when she decided to apply for an executive MBA several years ago. She looked at several but says it made financial sense to enroll in JMU’s program since the university, as her employer, would pay for it.

“Our cohort was small, around 20 people. When it’s that small, you rely on each other for a lot. Some of my classmates are still mentors for career growth, some on how to navigate my career,” she says. “We still stay very close.”

Read graduated from JMU’s executive MBA program in 2018 and in 2020 became the university’s spokesperson and director of communications. She’s now its manager for state government relations.

Getting facetime

One important aspect of MBA programs that has remained the same is networking, even in the post-pandemic era.

A report released in May by UNICON, a global consortium of business-school-based executive education organizations, found that the pandemic opened people’s eyes to what could be accomplished in online MBA classes, but there’s still a strong preference for at least some in-person classes.

W&M’s executive MBA program, like those at other Virginia public universities, attracts students with anywhere from eight to 20 years of work experience who have C-suite ambitions. Others have started their own businesses or are preparing to do so, White says.

At the start of their education, students are paired with a certified leadership coach, whom they meet with regularly throughout the program, and they have access to executive partners — about 100 semiretired or retired executives who serve as additional advisers and mentors.

“The Executive Partners program is just a tremendous wealth of support and insight that we have at our fingertips anytime we want it,” Fleming says. “I can reach out to an executive within the marketing arena and learn from his or her experiences [and] have conversations. For example, we had one class where a group of executive partners came in and they did breakout discussions with us on a particular case. We spent time with them in small groups getting their perspective, and it was really exciting.”

VCU students are required to attend in person the first weekend of each month, then have the option of attending in person or online. During their summer semesters, they have the option to add a concentration in either corporate finance or health care management.

“One of the big benefits of the program is the networking,” Boyd says. “We feel it is really important to be integrated into their cohort.”

Although Fleming left Blackboard to start her own business before entering William & Mary’s MBA program, White notes that most of the university’s executive MBA students receive promotions or other career opportunities after earning their degrees.

“It’s very rare,” White says, “for someone to complete the program and have the same position at the end that they did in the beginning.”