RVA757 Connects strategy calls for more digital infrastructure along corridor

RVA757 Connects unveiled its 2035 Global Internet Hub Vision Plan to position the I-64 corridor as a hub for digital infrastructure.

Amazon buys 189 acres in Prince William tech park for $700M

Amazon Data Services has bought approximately 188.5 acres in Prince William County for a whopping $700 million.

Anthropic invests $50B in AI data centers, Microsoft expands

Anthropic plans $50B in AI data centers; Microsoft builds new Atlanta facility as tech giants expand energy-heavy AI infrastructure.

New documents reveal scope of Google’s Chesterfield data center campus

Google plans to build an 855,846-square-foot data center campus on a roughly 307-acre property in Chesterfield County.

Irish data center power manufacturer opens first US plant in James City County

An Irish energy infrastructure manufacturer focused on data centers will establish its first U.S. plant in James City County, a $5.225 million investment expected to create 250 jobs, Gov. Glenn Youngkin announced Wednesday.

Northern Virginia AI startups raise millions

This summer, investors poured money into Northern Virginia-based AI startups offering solutions for data centers, the military and bias in AI. In July, Emerald AI — incorporated in Washington, D.C., but with primary offices in Clarendon — launched with $24.5 million in seed funding, and Rosslyn-based Rune Technologies raised $24 million in a Series A […]

Despite federal coal support, Southwest Virginia aims to diversify

Southwest Virginia pursues nuclear, data centers, clean energy projects as coal declines and communities seek new economic paths.

Dominion plans more natural gas, solar in 20-year forecast

Virginia's future could hold more solar and natural gas power generation, according to an integrated resource plan filed by Dominion Energy this month.

Virginia garden center lays off 97 after $160M sale to data center developer

Merrifield Garden Center will close its Gainesville facility this December, laying off 97 employees, following a $160 million property sale.

BlackRock, Nvidia, Microsoft in $40B data center deal

BlackRock, Nvidia and Microsoft are buying Aligned Data Centers for $40B to expand global AI and cloud infrastructure.

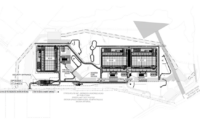

Newport News targets 12 sites for development

During a economic development summit on Thursday, Newport News city leaders unveiled 12 sites they want to see redeveloped.

CoreWeave signs $14 billion AI infrastructure deal with Meta

CoreWeave will provide Meta $14B in AI cloud computing power through 2031, boosting share prices and fueling AI infrastructure growth.