Tight squeeze

Bigger ships prompt calls to deepen and widen channels

Tight squeeze

Bigger ships prompt calls to deepen and widen channels

January Collins should be nervous.

In about 20 minutes, she’ll guide a ship longer than three football fields through the channels of Hampton Roads.

The harbor pilot leans calmly against the side of the pilot boat, a coffee cup in one hand, as the boat zips to meet the 1,200-foot-long ship five miles off the coast of Virginia Beach. The massive ship is larger and has more capacity than the largest vessel Collins has ever steered.

Training, though, breeds confidence. “We did training down in Louisiana to prepare for these larger vessels,” Collins says of Virginia’s 45 harbor pilots who guide ships of all sizes through Hampton Roads’ channels. The Maritime Pilots Institute gave them a feel for piloting these massive vessels through manned-scale models and simulations.

That program came on top of years of extensive training required for Virginia’s licensed harbor pilots. Collins is the commonwealth’s only woman pilot. As apprentices, these men and women rarely leave the Virginia Pilot Association’s brick headquarters in Virginia Beach, which includes dormitories.

By the time pilots become fully licensed after six years of training, they have steered or accompanied a master pilot on more than 2,300 vessels. They also have memorized every buoy, shoreline, water depth and obstruction along the waterways leading to Virginia’s marine terminals to pass Virginia’s rigid exams. And they have attended training programs around the world.

The OOCL Malaysia — the vessel Collins is about to board — is part of a class of container ships that first began visiting the East Coast in May. These massive vessels bring goods from Asia through the newly widened Panama Canal. The OOCL Malaysia has a cargo capacity of 13,208 TEUs or 20-foot-equivalent units.

Before May, the largest ship the port had handled was around 11,500 TEUs.

The port now handles ships of 13,000 to 14,000 TEUs on a weekly basis — and likely will see them more often.

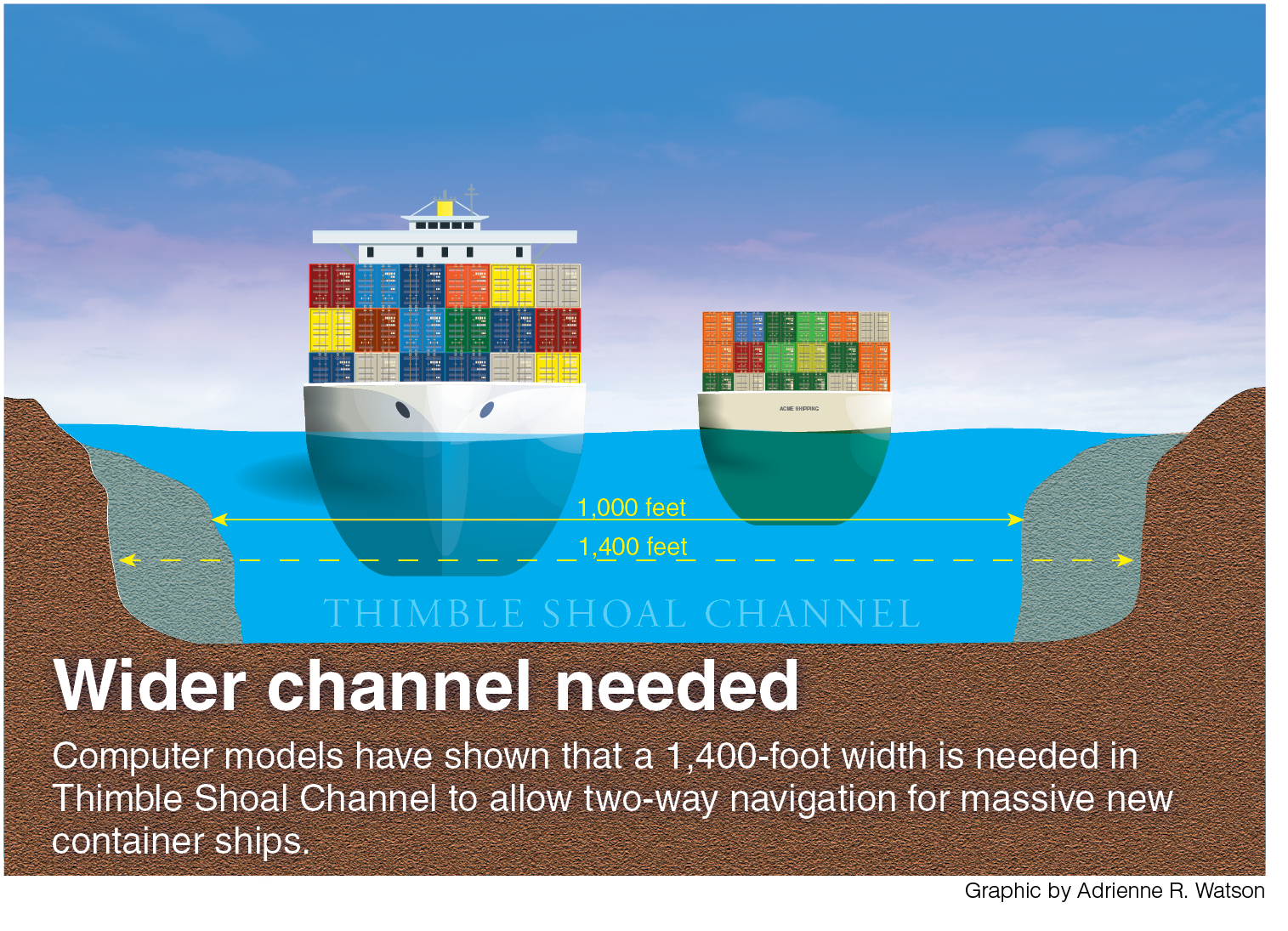

The arrival of these ships highlights the maritime community’s push to deepen and widen its channels. These ultra-large container vessels (ULCVs) require a section of the port’s busy channels to be restricted to one-way navigation as they enter or leave Hampton Roads, which can back up traffic in the port. “[The widening and dredging project] is by far Hampton Roads’ number one priority,” says Art Moye, executive vice president of the Virginia Maritime Association. “If we’re to have a future, and we’re to take full advantage of what’s happening as far as the global shipping world is concerned, deepening and widening our channels is of the utmost importance.”

Bringing the ships in

The average size of container ships has grown rapidly since Collins joined the pilots’ program in 2006. “Sometimes I don’t have an appreciation for how big they are until I’m standing right next to them,” she says.

Now it’s time for a close-up. As the pilot boat approaches the OOCL Malaysia, Collins snaps on her sunglasses, throws on a collared life vest and picks up a backpack carrying a high-tech navigation system. The water is calm this morning, and Collins climbs up the side of the big ship with ease.

The huge ships require pilots to make many adjustments as they guide the vessels into port. They carry so many cargo containers that the bridge, where the navigation system is housed, is now in the front of the ship. That means that about 800 feet of the ship is behind Collins as she navigates the channel.

From the time Collins climbs aboard, the 28-mile journey to a berth at the Port of Virginia’s Norfolk International Terminals on the Elizabeth River takes four hours. These ships are so big, in fact, a tug boat is attached to the back of the massive vessel on the final few miles to slow it down. (A docking master is charged with parking the ships at terminals’ berths.)

Cofer also points out that harbor pilots often have to compensate for the wind when coming through a channel by navigating at a slight angle. That means that if a pilot needs to steer the ship at an 8-degree angle, the width of the ship (about the width of a football field) has effectively doubled.

The port community has been working to accommodate the restrictions needed to handle the massive vessels, and maritime executives say the coordination has gone well.

Through stakeholder committees of the Virginia Maritime Association, the Coast Guard is leading discussions to develop rules for managing ship traffic when these large vessels call on the port. “As we experience more of these and as we get a better handle on what the turnaround time will be for these vessels, I think that we’re getting fairly close to coming up with some practices that the port community accepts,” says David White, vice president of the Virginia Maritime Association.

Yet coordination can go only so far. The morning the OOCL Malaysia was scheduled to come in, two ships were adjusting their schedules to accommodate for channel restrictions, Cofer says.

Closing down a portion of the channel is not unusual. Many other ports on the East Coast face similar schedule restrictions.

The situation also isnt’ completely unusual locally. The Hampton Roads channels are busy. Not only do they handle container ships, but grain, coal, bulk and breakbulk, and Naval ships. For security purposes, channels close down when aircraft carriers move in and out of the port.

With ocean carriers deploying more big ships to the East Coast, the Port of Virginia could face bottlenecks. “It’d be like somebody saying, ‘Let’s shut down Interstate 95 and just do one way,’” says Cofer.

Deeper and wider channels

The Port of Virginia and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers are funding a study to re-evaluate the economics and engineering of dredging the river. The Hampton Roads channel received congressional approval to dredge to 55 feet in 1986, but the new study is required for the project to move forward.

The study’s final review is expected to be ready by the summer of 2018, but the port and the corps plan to begin the engineering and design phase of the project before then. They were expected to reach a “tentatively selected” plan by Aug. 25 after this story went to press.

The design process would run concurrently to the corps’ final review on recommendations for the correct water depth and channel widths needed. “We are aware that we may have to pivot along the way in some areas, which is to be expected,” says Joe Harris, spokesman for the Port of Virginia.

The engineering and design phase is expected to take 12 to 18 months to complete and construction could begin as soon as the second quarter of 2019, says Harris. Construction would take another three to five years.

One challenge could be the cost of the project. The dredging and widening is estimated to cost $300 million to $400 million. Responsibility for funding such projects typically is split between the state and the federal government.

The port says that, while it understands that federal resources are limited, funding from Washington is appropriate because the dredging project would have benefits for businesses inside and outside Virginia. “The investment would drive growth and productivity in various industries as they would be able to import/export their products, components and raw materials quicker; and consumers would benefit from an increasingly efficient logistics and supply chain,” says Harris.

Moye of the Virginia Maritime Association, says the state should be willing to put up funds if federal money isn’t approved. “It needs to happen regardless of what the feds tell us they are able to do at the time the project is ready to get started,” says Moye. “We need to be prepared to find and secure that funding without any further delays, and that may be looking to the state.”

So far, the ULCVs coming to the Port of Virginia have been loaded relatively lightly, says Cofer, which means they haven’t come close to the channel’s 50-foot depth yet. But that situation is likely to change, says Cofer. Massive ships are likely to arrive more fully loaded as ocean carriers adjust to new service lines and slot-sharing agreements.

The rise of bigger ships

The world’s shipping lines saw a major change in April when the number of alliances involving different companies was reduced from four to three. The alliances allow the ocean carriers to put containers on each other’s ships.

The Ocean Alliance, which includes ocean carriers CMA CGM, Evergreen, OOCL and Cosco Shipping, started a new service line that is deploying ULCVs to the East Coast in May.

The main impetus behind bigger ships was the widening of the Panama Canal, says Bill Ralph, a maritime consultant with R.K. Johns and Associates in New Jersey. “With the expansion of the Panama Canal, that’s kind of equalized the opportunity for the carriers to get their ships the most efficient, cost-effective way to the East Coast,” says Ralph.

The locks of the Panama Canal previously could handle only ships that were about 5,000 TEUs in size. Following an $5.4 billion expansion completed last year, the canal now can handle ships as large as 14,000 TEUs. “The Panama Canal business [in terms of larger ship size] is coming faster than we thought it would,” Ralph says.

He says that last year’s bankruptcy by the South Korea-based ocean carrier Hanjin Shipping raised a red flag for the industry, pushing carriers to find ways to rein in their costs. Hanjin, Ralph points out, represented about 8 percent of the volume of its ocean carrier alliance. “When you look at someone who had 8 percent of the trade go bankrupt, the other carriers were forced to make dramatic changes,” he says.

Compared with 4,500-TEU ships, the ULCVs visiting the port today can generate a 25 percent cost saving for carriers, he says.

Another pivotal event occurred earlier this year when the Bayonne Bridge leading into the Port of New York and New Jersey was raised. That bridge previously blocked large ships from reaching the East Coast’s busiest port.

The ocean carrier alliances have not made any public changes to their rotations since the bridge was raised, but experts believe the development will drive more cargo and ships to other East Coast ports. Ships typically visit multiple East Coast ports, so opening the largest container port on the coast could attract more of these ships.

The amount of cargo brought in will depend in part on each port’s ability to manage the large amount of cargo coming off these vessels all at once, says Ralph. “It will really be a function of how terminals operate their facilities because there will be a lot more containers offloaded at once,” says Ralph.

On the land side, the Port of Virginia, which handled a record 2.76 million TEUs of cargo last year, is growing capacity of its two largest container terminals 40 percent, with projects totaling $670 million. “We know the cargo loads on these vessels are going to increase, and we are already planning to ensure that we have the appropriate processes, cargo conveyance equipment, communications network and labor force in place to maintain our efficiency for when that moment arrives,” says Harris.

While the level of cargo has increased, the number of ships calling on the port is falling because of the deployment of larger vessels. “If you look at the size of ships being built, as older ships are replaced, soon we’re only going to have big ones left,” says Cofer.