By the book

The 7 habits of the highly effective Stephen Moret

By the book

The 7 habits of the highly effective Stephen Moret

On a sunny, crisp fall morning in late October, Virginia Gov. Ralph Northam stood at a lectern in the atrium of Danville’s Institute for Advanced Learning and Research, announcing to the assembled reporters and dignitaries that van manufacturer Morgan Olson LLC would be taking over a local factory about to be abandoned by Swedish furniture maker Ikea.

Instead of losing 300 jobs, the rural region would see a net gain of more than 400 new positions, along with a $58 million investment. A key factor in the Michigan-based company’s decision to locate in Virginia, Northam said, was the commonwealth’s new custom recruitment and workforce-training initiative, the Virginia Talent Accelerator Program.

While the cameras focused on the governor and the company’s leaders, the man who had made the day possible waited quietly behind the scenes. But everyone in front of the cameras knew that almost every aspect of this success, including the job program, was the work of the Virginia Economic Development Partnership and its CEO and president, Stephen Moret.

Moret — the man who resuscitated the state’s business-recruitment arm, reinvented the way Virginia works with businesses and landed what might be the largest economic development project in U.S. history, Amazon’s second headquarters — steers clear of the spotlight. He works hard to keep it trained on others.

It is because of his innovative — and highly effective — captaining of VEDP that Virginia Business has named Moret its 2019 Business Person of the Year.

Balding, bespectacled and soft-spoken, Moret seems an unlikely economic spark plug. He doesn’t even play golf. But those who know him say he’s a relentless worker and inspiring collaborator.

“Stephen is one of the most accomplished and brightest economic development agency leaders I have worked with in the industry,” says Mark Arend, editor of industry journal Site Selection.

A book made it possible.

#1 Be proactive

Moret, 47, was born in rural Mississippi, the great-grandson of former sharecroppers. His parents divorced when he was about 6; he rarely saw his father after that.

His mother, Phyliss Moret, was a pharmacist at the same small-town drugstore where she had worked her first job as a soda jerk. A few years later, she landed a job running the state’s trade organization for pharmacists, and she moved with young Stephen and his little brother to a larger town near Jackson, the state capital.

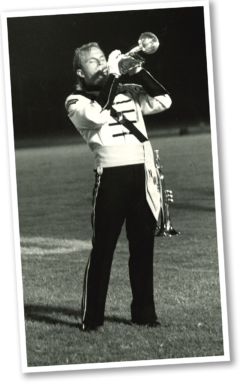

By middle school, Stephen had taken up the trumpet. It was the first activity he’d discovered where he saw clear results from hard work, he says — the more he practiced, the more he heard himself improve.

His mother was pleased. “In small-town Mississippi, kids are into music or sports,” Phyliss Moret says. “I am not so excited about sports.”

His mother scraped together funds for trumpet lessons. Family finances were tight; she couldn’t afford her son’s teen infatuation with Ralph Lauren shirts.

“We were not poor,” Stephen Moret says, “but we were definitely lower-middle-class.”

Affable and driven, Moret aimed to excel. “It wasn’t enough for him to be in band,” his mom says. “He wanted to be All-American.”

By high school, Moret proved himself a dedicated and skillful trumpeter, named among 104 students nationwide to march in the annual

Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade in New York City as part of the McDonald’s All-American High School Band. He loved spending time with friends, many of them his comrades from the school marching band. Meanwhile, he’d become interested in engineering and occupied by robotics competitions.

But with so many distractions, his usually stellar grades slipped. And in his junior year of high school, he was at risk of failing two classes.

At that decisive moment, someone — Moret thinks possibly an uncle — gave him a copy of a recently published business book: “The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People,” Stephen R. Covey’s now-classic blueprint for professional and personal success.

Moret devoured it. Over that spring and summer, he studied Covey’s book as a roadmap. It offered tools for living a successful life. With it, Moret laid out his goals and plans.

He earned straight A’s his senior year.

“That book kind of changed my life,” he says today.

#2 Begin with the end in mind

With the blip on his GPA, MIT and Rice University were no longer options. Moret’s trumpet teacher suggested Louisiana State University in Baton Rouge. Moret knew nothing about LSU — he recalls asking what the letters stood for.

Moret won a full music scholarship at LSU, a position on the Tigers marching band and a small stipend. He double-majored in music performance and mechanical engineering.

The marching band demanded an enormous commitment. Eventually Moret asked to withdraw from his music major and the band. Remarkably, the university allowed it — and let him keep his full scholarship. (His 4.0 GPA presumably helped.) Moret speaks often of this with gratitude.

Unencumbered by the marching band, he threw himself into student politics and fraternity life, which are intertwined at LSU. Elected student body president (his campaign motto: “Cooperation, Service and Integrity”), he led a plan to revise the student government’s constitution to fix recurring electoral problems. He also served as one of two student representatives on a state government reform commission.

The experience was life-changing. “I had gotten this bug to help transform the state government of Louisiana,” Moret says.

#3 Put first things first

After college graduation, Moret spent a few unsatisfying years as an engineer. After one of his mentors,

William Jenkins, was named LSU chancellor, Moret persuaded Jenkins to create a job for him as his assistant. Moret, Jenkins says, was “a godsend” in the role.

In 1999, Moret was accepted to the master’s program at Harvard Business School. In his application, he wrote that he dreamed of becoming state economic development director for Louisiana.

Moret stood out at the business school, where he was elected co-president of the student body. Stephen Waguespack, now president and CEO of the Louisiana Association of Business and Industry, remembers meeting Moret then: “He’s just one of those guys — you just know he’s going to be successful.”

At a Cambridge potluck in 2000, Moret met Heather McMillen. She was pursuing a doctorate in education at Harvard, which he found intimidating. (She earned her doctorate in 2009.)

The two fell into a long conversation about public policy. They started dating. “I had never met anybody who was so passionate about a state,” Heather says now. She and her roommates nicknamed him “Louisiana Man.”

They married in 2002. After graduating from Harvard, Moret took a job near Washington, D.C., with the global management consulting firm McKinsey & Company, while Heather took a fellowship at the Brookings Institution. The couple kept a hand in politics; Stephen was policy director for Republican Bobby Jindal’s first campaign for governor of Louisiana. After Jindal lost a close election in 2004, the Morets decided to move to Louisiana, where Stephen landed a job running the Baton Rouge Area Chamber of Commerce.

#4 Think win-win

In Baton Rouge, Moret gained his first true management experience. He also built partnerships and “turned a rather sleepy chamber of commerce into one of the most dynamic economic-development organizations in the state,” says John Spain, executive vice president of the Baton Rouge Area Foundation.

Moret concluded that Louisiana’s reputation for corruption — what the Baton Rouge Advocate called “Louisiana’s long-tarnished image as a corrupt backwater” — wasn’t just an ethical problem. Businesses stayed away because of it, studies showed.

His wife suggests Moret took the state’s reputation personally: “Authenticity and credibility are very important to him.”

Spain agrees: “It was extraordinarily personal. People would say, ‘How can you do business in a place like Louisiana?’ He was offended.”

In 2007, Moret put together a coalition, including chambers of commerce and other business groups, to push for an overhaul of Louisiana’s ethics laws. Its suite of reforms came within a hair’s breadth of passing in the state legislature.

#5 Seek first to understand, then to be understood

In his second try for the governorship, Jindal again turned to Moret as an adviser. When Jindal took office in 2008, he hired Moret as

Louisiana’s secretary of economic development, a state Cabinet position overseeing a $41 million annual budget. It was barely two years after Hurricane Katrina. The Great Recession was exploding.

While Jindal was still campaigning, Moret had traveled to Georgia to study an innovative program that trained workers to meet the needs of companies. He returned with the inspiration that became Louisiana’s FastStart, a system to quickly train workers in skills needed by specific businesses or sectors at no cost. (He also recruited one of Georgia’s top people to run it.)

FastStart offered clear benefits for companies to work with Louisiana and became the underpinning for a string of economic wins. By 2010, just two years after Moret’s trip to Georgia, FastStart was named the country’s best state workforce program by Business Facilities magazine, bumping Georgia from the top spot.

A suite of ethics reforms modeled on those Moret had pushed a year earlier passed during a special session held in Jindal’s first year in office. In one year, Louisiana shot from 46th to fifth in the annual state government integrity rankings from the Chicago-based Better Government Association.

Moret became known as Jindal’s “Swiss Army-knife Cabinet secretary” for his versatility, says Waguespack, then Jindal’s chief of staff.

Political fights were constant. Jindal had signed off on tax cuts in the face of the recession. “There were dog fights for the few crumbs that there were,” Jenkins says.

Over his two terms, Jindal slashed funds for higher education by 55%, the largest such reductions in the nation; like other states’ colleges at this time, the institutions recouped their losses by raising tuition. “Horrible times,” says Jenkins, then LSU’s president.

“Painful,” Moret calls those cuts now. “I can’t think of a better word.”

One fierce critic was Robert Mann, a former columnist for the New Orleans Times-Picayune and former spokesman for Democratic Gov. Kathleen Blanco.

Jindal “balanced the budget on the backs of higher ed and poor people,” says Mann, now a professor of communications at LSU.

Despite the difficulties, Louisiana’s economic image improved. CNBC and Site Selection magazine both lauded the state’s strong showing — $100 billion in overall development over the eight years of Jindal’s tenure, by Waguespack’s tally; Moret cites $62 billion in private industry expansion.

#6 Synergize!

By the end of the Jindal administration, Moret was being name-checked as a potential new president for LSU. Mann wrote columns charging that Jindal was pushing for Moret to be LSU president. Others argued that Moret’s lack of a doctorate made him unsuitable.

Whatever the reason, the job offer never came. Moret says he can’t say whether he would have taken it. (Former LSU head Jenkins says Moret would have.) Instead, he was hired as head of LSU’s fundraising foundation.

“He was competing with people who had decades of experience,” says Clarence Cazalot, a former Marathon Oil Corp. CEO who helped hire Moret for the foundation job. “But his passion for LSU and his incredible intellect made him stand out.”

Soon after Moret accepted the position at LSU, he made a surprise phone call to Mann, the former newspaper columnist who had been his most outspoken critic during the Jindal administration.

“We had a really nice conversation,” Mann recalls. “He said, ‘I’m in a new role here and we’re on the same team now.’ He and I found a number of ways to work together. He could not have been more supportive. … He turned out to be not just competent, but very capable. I wish we still had him.”

Moret put together a plan for a $1.5 billion LSU fundraising campaign, the largest in state history. He also completed work on a doctorate in higher education management from the University of Pennsylvania.

Then Virginia came calling.

In 2016, the Virginia Economic Development Partnership’s reputation was in shambles. A series of bad deals had given the state government’s economic development arm a black eye. The General Assembly ordered a full review from the Joint Legislative Audit and Review Commission.

A search began for new leadership.

At the urging of a mutual acquaintance, Barry DuVal, president and CEO of the Virginia Chamber of Commerce and a former state secretary of commerce and trade, reached out to Moret about the VEDP job.

Moret was interested. He had lived in Arlington while working for McKinsey. A few years earlier, his mother had moved to Richmond to be an assistant dean at Virginia Commonwealth University’s pharmacy school.

After his experience as a gubernatorial Cabinet member, Moret found VEDP’s independent structure refreshing. And he knew Virginia had a long record of economic success. Moret decided he wanted the job.

Delegate Chris Jones, R-Suffolk, who oversaw the JLARC study on VEDP, opposed the idea of hiring a new CEO for the organization before JLARC’s review was made public. Then-Commerce and Trade Secretary Todd Haymore, a member of the partnership’s board, argued otherwise.

As a compromise, in late 2016 Haymore arranged for Moret to review the almost-finished draft of the JLARC report. Moret was escorted to the fourth floor of the Patrick Henry Building in Richmond and shut in a conference room with the draft report, no cameras allowed.

Moret spent hours alone in the conference room, taking notes. The JLARC analysis was brutal, citing failures at all levels of VEDP and calling for dozens of changes, some dramatic. (“In my 22 years, I’ve never seen an agency with this level of dysfunction,” JLARC’s head would say of VEDP upon the report’s release.)

When he emerged, Moret recalls, “I said … ‘This is going to be a good bit of work, but it makes sense.’”

He took the job.

Moret hit the ground running. He created a detailed road map to swiftly enact the changes recommended by JLARC (“The only way to position VEDP for a bright future [was] to implement substantially everything in the report,” he says) and to improve the state’s national rankings.

He met with development directors and business groups across the state. He convinced the General Assembly to reinstate VEDP’s marketing budget — it had previously been zero. He unwound some of the state’s unsuccessful incentive deals. Using VEDP’s standing board positions, he strengthened its working relationship with the Virginia Port Authority and Virginia’s higher education system, especially the State Council of Higher Education for Virginia and the community college system.

“He put the ‘P’ back in partnership,” DuVal says.

Relentless travel was one tool; Moret often is on the road two or three weeks out of most months, hopscotching the state, the country and the globe to talk up Virginia and meet with business and political leaders. In one recent week, he was in a different state every day.

Data was another tool employed by Moret.

Moret “overwhelms you with details. I’ll tell him, ‘Stephen, come on! I can’t read four inches of printouts!’” says John “Dubby” Wynne, former president and CEO of Norfolk-based Landmark Communications and a member of the VEDP board.

As Delegate Jones recollects, “At first I said, ‘You’re giving me way too much information. You’re killing me with paper!’” In time, Jones got the point: “He understood that trust had to be rebuilt between VEDP and the General Assembly.”

Moret had been on the job for all of eight months when, shortly after Labor Day 2017, Amazon.com Inc. put out the word that it was seeking proposals from states for incentives to attract the company’s $5 billion, 50,000-worker second headquarters.

Even to win Amazon, Moret knew Virginia’s tightfisted General Assembly would never approve the huge economic giveaways that many other states would be offering. Virginia would have to compete on other terms.

Drawing on his experiences in Louisiana, his wide reading in economic theory and the Virginia economic-development plan his team had just completed, Moret came to believe the commonwealth’s best chance with Amazon lay in showing the e-tail behemoth that the Old Dominion had the best resources for building a strong tech workforce.

“Talent, talent, talent,” says Moret, who crisscrossed the state to build partnerships in support of the endeavor. Eventually, he presented a detailed proposal to the General Assembly’s powerful Major Employment & Investment Projects Approval Commission for the commonwealth to spend more than $1 billion strengthening high-tech education across Virginia, including building the Virginia Tech Innovation Campus in Northern Virginia. The commission signed off.

Moret’s insights proved correct. In early 2019 — 14 months after its announcement — Amazon took the deal, agreeing to invest $2.5 billion to locate its HQ2 headquarters and 25,000 jobs in Arlington.

Moret often deflects credit for Virginia landing Amazon, pointing out that more than 500 people worked on the bid.

“It was a great team effort,” agrees Haymore, “… but Stephen was the quarterback.”

#7 Sharpen the saw

What does the future hold? Moret ticks off his VEDP to-do list, which includes pushing Virginia to the top of more national business rankings, shepherding the nascent Talent Accelerator training program and strengthening rural development.

Others see a bigger future in store for him. “I would be stunned if five years from now he hasn’t done something greater than Amazon. Because that’s him. That’s who he is,” says Victor Hoskins, president and CEO of the Fairfax County Economic Development Authority. “Secretary of commerce? The U.N.? World Bank? I’m not kidding; this guy is that kind of caliber.”

Those who work with Moret encourage him to back off from his Herculean work habits. He and his wife have four children, ages 5 to early teens. Stephen’s mother has now retired in Richmond, and Heather Moret’s parents have just moved to the area.

“We don’t want him to burn out,” says Haymore, now a managing director at Hunton Andrews Kurth. “He needs to work on the life-balance aspect.”

Phyliss Moret agrees: “I tell him all the time, ‘Remember the seventh habit!’”

In Covey’s book, the seventh habit — “sharpen the saw” — emphasizes the importance of spiritual growth and a healthy personal life.

After years of her husband’s seven-day work weeks and frequent travel, Heather Moret supports that idea.

But, she says, she knows that drive is part of who he is.

“He would prefer to be here with us, but he’s not: ‘It may be midnight and I may be exhausted, but I promised this, and I am going to be sure I get it done.’”