Balancing act

Divided legislature leads to compromise, tension

Mason Adams //June 28, 2022//

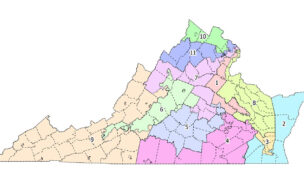

The Virginia General Assembly returned to a familiar configuration in 2022, legislating with a Republican-majority House of Delegates and Democratic-controlled Virginia Senate for the seventh time since 2000.

But while the partisan split was old hat, much else about the session was new, taking place two years into the global COVID-19 pandemic and occurring after two years of Democratic control that brought progressive priorities to the Old Dominion.

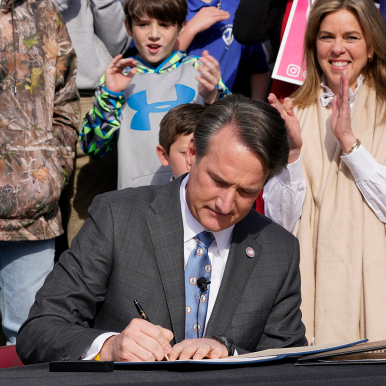

The session also featured a new player: first-year Gov. Glenn Youngkin, a Republican businessman who had never served in elected office until his January inauguration.

From a business perspective, the partisan split’s not necessarily a bad thing, politicos say.

“As many lobbyists tell me, divided government tends to be a better construct for them as they try to help their associations and clients,” says Chris Saxman, a former Republican delegate and executive director of Virginia FREE. “There’s more competition from the parties, [and] competition is good. It draws out what are important issues, policies and sometimes demeanor when it comes to being successful.”

With CNBC naming Virginia its top state for business for the past two years, neither party was incentivized to make major changes that could negatively affect that unprecedented ranking.

Yet the legislative session’s relatively staid results belie the partisan acrimony that simmered in Richmond. Youngkin and House Republicans tried to reverse course after two years of Democratic control, but were stopped by Senate Democrats. At times, the partisan divide took a personal turn, as the parties clashed over the budget and confirmations at the Capitol, and in blunter terms on social media.

“We approached the session with an understanding that Democrats still controlled the Senate,” says House Speaker Todd Gilbert, a Republican from Shenandoah County. “We knew amending or reversing policies passed under complete Democratic control wouldn’t be likely.”

After the session, “I think the bottom line is, we’re roughly in the same place,” says Sen. John Bell, a Democrat from Loudoun County. “I think people from both sides want to keep that label as being business friendly. If we allow the extremes of either party to go through, we wouldn’t be. And that would be a major problem.”

While Virginia is familiar with a divided legislature, the gulf between parties appears deeper than at any time in modern history. Partisan politics have become even more polarized, while Donald Trump’s presidency and ongoing influence in the GOP have disrupted party alignments and priorities in ways still playing out now.

Youngkin swept into office last year on a wave of momentum from suburban voters motivated by battles over public school policies and curricula, as well as weariness with pandemic-driven mask mandates and other regulations. The former Carlyle Group co-CEO was sworn in on Jan. 15 and immediately signed 11 executive actions, including allowing parents to decide whether their children should wear masks in schools, attempting to withdraw the state from a regional carbon trading market and declaring Virginia “open for business.”

Six days later, Youngkin announced his package of legislative and budget priorities, including measures to eliminate the grocery tax and to create 20 charter schools across the state. On Feb. 7, his press office issued a news release, “Governor Youngkin Delivers on Promises, Day One Game Plan Bill Passes House of Delegates.”

That momentum proved to be a mirage, though, as the Virginia Senate soon became an insurmountable hurdle for much of Youngkin’s agenda.

Some victories, some defeats

That’s not to say the governor didn’t have wins. The Senate backed a proposal by Sen. Siobhan Dunnavant, R-Henrico, to keep schools open five days a week for in-person instruction and to ensure a parental opt-out from school mask mandates.

“I promised that … Virginia would move forward with an agenda that empowers parents on the upbringing, education and care of their own children,” Youngkin said after the vote. “I am proud to continue to deliver on that promise.”

And, in budget negotiations, Youngkin’s platform to repeal grocery taxes was partially successful, with the 1.5% state portion eliminated but retaining the 1% tax for localities. Also, $100 million will go toward the College Partnership Laboratory Schools Fund to establish K-12 “lab schools,” public, nonsectarian institutions housed in colleges and universities.

But the Senate blocked many Republican initiatives, including a gas tax holiday, reversing an increase in the minimum wage and banning teaching of “inherently divisive concepts.” Meanwhile, the GOP took aim at “critical race theory,” an academic lens for examining how race is built into societal institutions that superintendents deny is taught in public schools, but typically used by partisans to encompass classroom instruction on racial issues and history.

The Democratic-controlled Senate also rejected former Trump administration Environmental Protection Agency head Andrew Wheeler to serve in Youngkin’s Cabinet as secretary of natural and historic resources, although Wheeler is serving as an adviser to the governor now. That set off an escalating feud as the Republican-led House then blocked 11 of outgoing Gov. Ralph Northam’s appointees to different boards and commissions, and the Senate then rejected all but one of Youngkin’s nominees to the parole board.

Amid the tension, Senate President Pro Tempore Louise Lucas, an eight-term Democratic senator from Portsmouth, became the face of Youngkin’s opposition on social media as she accrued more than 64,000 followers for her biting commentary on Twitter. In one memorable moment, she tweeted about a text message Youngkin sent her complimenting her for a speech that was instead made by another Black female senator, Mamie Locke, D-Hampton. The governor apologized, and Lucas and Locke later wore replicas of Youngkin’s signature red vest on the Senate floor.

All humor aside, “I want to give voice to what’s happening to us as voters,” Lucas says. “A lot of people got hoodwinked by him [Youngkin]. They didn’t know he had all these Trumpian policies.”

Youngkin made his own move to communicate more directly to voters, purchasing an ad during March Madness basketball games to pressure Democratic lawmakers to approve his budget priorities. Sen. Adam Ebbin, D-Alexandria, dismissed it as “a gimmick.” Youngkin later vetoed nine of Ebbin’s 10 bills that passed the legislature, apparently in retaliation for Ebbin’s role in blocking his nominees.

The governor won some legislative victories, including the passage of a bill to let parents opt their children out of reading assigned material with sexual content. But more often his accomplishments came from nonpartisan economic development announcements such as the recent decisions by Raytheon Technologies Corp. and The Boeing Co., the world’s second- and third-largest defense contractors, to relocate their global headquarters to Arlington.

“I’m pleased with what we got done in the House, but I do wish we had been able to get more through the Senate,” Gilbert says. “We had lots of good bills come out of the House just to die in Senate committees.”

Holding firm

Democrats view the session differently, noting that many of their signature accomplishments from the last two sessions remain intact.

“The firewall held,” Bell says. “One thing that was wise was that many of the partisan pieces of legislation from the House didn’t make it out of the House, and partisan legislation from the Senate didn’t make it out of the Senate. It’s a good thing that far reaches from right or left aren’t going to pass.”

Take the Virginia Clean Economy Act, a 2020 law that commits to decarbonize the state’s electric grid by 2050, ending the use of coal to generate power and incentivizing more solar and wind. Every House Republican voted in favor of a bill to roll back the law, but the repeal attempt was swiftly killed in a Senate subcommittee.

“A wise thing I’ve learned, often stated by people of both parties, is that when new legislation is passed, give it a couple of years until you make any changes,” Bell says. “Most of this legislation, the ink is pretty wet.”

The General Assembly, however, “nibbled around the edges” on energy policy, says House Majority Leader Del. Terry Kilgore of Scott County. That included passage of a bill to remove power from citizen air and water control boards, after the former blocked permitting for a compressor station on a Mountain Valley Pipeline extension.

Youngkin also vowed to withdraw Virginia from the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative, an 11-state carbon market to cap and reduce greenhouse emissions in the power sector. He wasn’t able to do so immediately by executive order because Virginia’s membership was enacted by the seven-member citizen state air pollution control board. However, he has appointed two new members — former electric cooperative executives — to the board, which can then fulfill his edict.

The General Assembly failed to pass a two-year budget until June, when lawmakers finally approved a compromise that increased the standard tax deduction for individuals and joint filers without doubling it, as Republicans had called for. The budget also included $1.25 billion for school construction and modernization, and $159 million for the Virginia Economic Development Partnership to develop more “megasites” of the type that have been targeted by auto manufacturers who’ve recently announced new factories in Georgia, Kentucky, North Carolina and Tennessee — but not Virginia.

Democrats also used the extended session to elect a new House minority leader, Del. Don Scott Jr. of Portsmouth, after ousting Del. Eileen Filler-Corn in April. Filler-Corn served as Virginia’s first female and Jewish speaker when Democrats held the chamber in 2020 and 2021.

Virginia lawmakers frequently have needed extra time to resolve budget impasses beyond the end of the regular session, a problem for businesses as well as localities waiting to set their own budgets.

“It’s become something of a tradition that needs to be broken, because it sends a signal to everyone in Virginia that deadlines don’t matter, when in fact they do,” Saxman says. “The business community grows increasingly uncomfortable with both parties when they can’t resolve what are frankly in the business world easily resolvable issues.”

Football fumbles

As of early June, there was still no resolution on a bill to award a state subsidy to attract the NFL‘s Washington Commanders to build a stadium in Virginia. Early in the session, subsidy estimates ran as high as $1 billion, but through the spring fell to $350 million as headlines about an allegedly hostile work culture continued to plague owner Daniel Snyder. Key Democrats and Republicans supported the proposal, but it ultimately failed to come up for a vote — largely from concern about going into business with a troubled organization.

The Ashburn-based football team and its ownership have been under investigation for allegations of sexual harassment and workplace misconduct, and Virginia Attorney General Jason Miyares announced in April that his office was investigating allegations the franchise engaged in financial improprieties.

“There are many, many studies that show that jurisdictions that are very generous to football teams do not recoup an effective return on their investment,” says Stephen Farnsworth, a political scientist at the University of Mary Washington. “This seems doubly true in the case of a legally-challenged and performance-challenged football franchise.”

In late May, the Commanders acquired the right to purchase 200 acres in Prince William County that drove speculation about its plans. The team also was considering other sites in Prince William County and Loudoun County, as well as its current site in Landover, Maryland.

The state legislature also got involved in what had been a municipal matter: Richmond’s casino referendum. After city voters rejected the proposed $565 million casino developed by media company Urban One Inc. in November 2021, Richmond Mayor Levar Stoney, several City Council members and Urban One quickly regrouped and launched a plan for a second referendum vote in November, approved in March by council and a circuit judge.

Meanwhile, state Sen. Joe Morrissey, a Democrat who represents parts of Richmond and Petersburg, had already started efforts to move the project to Petersburg. His bill to get a referendum on Petersburg’s ballot this year failed, but he prevented Richmond from placing a second referendum on ballots until November 2023 via a budget amendment.

As of early June, Richmond and Urban One officials say they are examining their legal options.

Also in the air is regulating the retail market for marijuana, which Democrats legalized in 2021 without establishing a commercial structure. The Senate passed a bill to complete that work in 2022, but the House rejected it. However, retail sales of synthetic THC products like Delta-8 — which some Democrats and Republicans attempted to outlaw — were approved, and lawmakers also approved misdemeanor penalties for people caught in public with more than four ounces of marijuana.

“Democrats let the genie of legalization out of the bottle, and I don’t think there’s any going back from that,” says Gilbert, a former prosecutor. “But I’m concerned about the idea of having marijuana stores popping up in Virginia without regard to what’s being offered to consumers. We have a hard enough time keeping kids away from alcohol and tobacco, and some of these edible products that have come to market in Virginia look very enticing for kids.”

Lucas, who maintains an ownership stake in The Cannabis Outlet, a cannabis products store with branches in Norfolk and Portsmouth, says the legislature must deliver on its promise of a commercial cannabis market that includes social equity provisions for communities adversely affected by decades of marijuana criminalization.

“Polls show the majority of Virginians want to see marijuana legalized,” Lucas says. “African American and brown people have suffered the hardships of prohibition. How dare we have an industry this large leave out the folks who have suffered the most? We need to legalize recreational sales — I’m hoping by 2023, not 2024. Why are we penalizing people for things that would make them feel better and healthier?”

Saxman says it’s best that lawmakers take their time with a complex issue that affects not just retailers but other stakeholders, including insurers and the criminal justice system.

Others agree that complicated bills take time to find consensus — especially in a divided General Assembly.

“That shouldn’t surprise anyone,” Farnsworth says. “It’s a radical departure from the past. These are complicated issues and big changes. These are things that should take time.”

g