Are we there yet?

Virginia’s journey in fixing its roads has just begun

Are we there yet?

Virginia’s journey in fixing its roads has just begun

For more than a decade, the Northern Virginia Transportation Authority studied, evaluated and ranked the region’s most critical transportation projects but had no money to address them.

The authority was created in 2002 to determine how to spend money generated from a proposed 1 percent increase in the local sales tax rates. To the surprise of many, the sales tax increase was voted down in a referendum.

Nonetheless, the authority continued its work, deciding what needed to be done to unclog its vast transportation network.

So when the Virginia legislature in 2013 finally passed a landmark transportation funding bill, the authority was ready to roll.

The law included regional revenue streams for Northern Virginia and Hampton Roads. In the first three fiscal years since the law went into effect, the authority in Northern Virginia has allocated $535 million on 68 road and transit projects. Another $169 million has been programmed by Northern Virginia localities for their own projects.

Annually, the authority should have about $200 million to spend on regional projects, with another $100 million split among localities.

“[There’s been] a radical sea change in terms of how we think of transportation funding for Virginia,” says Marty Nohe, chairman of the authority and a member of the Prince William County Board of Supervisors. “Traditionally, the argument has been that Northern Virginia has been getting a pitifully small share of transportation money compared to the rest of the state. It’s because we’re taxing ourselves to do it … and that money is being spent quickly and wisely in our region.”

Virginia’s transportation funding has undergone a major transformation since 2013. The breakthrough legislation passed that year added the first infusion of new funds to Virginia’s transportation system since 1986 while creating the locally raised revenues for Northern Virginia and Hampton Roads.

But lower-than-expected oil prices and Congress’ failure to pass an Interstate sales tax have blown holes in the plan’s anticipated revenues. Years of neglect also have taken their toll and only about $1.2 billion is available for new capacity projects over six years. Revenues should improve, however, from a federal highway bill and proposed transportation construction funds under Gov. Terry McAuliffe’s budget.

To ensure money is spent wisely, the General Assembly enacted new legislation, designed to govern how the Commonwealth Transportation Board (CTB) prioritizes projects. This year will provide the first test of how these new criteria are being used to score and budget projects in Virginia’s six-year transportation plan. “This will bring much more transparency and accountability to the process,” says Virginia Transportation Secretary Aubrey Layne.

New money, new rules

The transportation law passed in 2013, known as HB2313, ended a long legislative stalemate over transportation funding. The bill, passed under the guidance of former Gov. Bob McDonnell, was expected to bring in almost $4 billion in new revenues over six years, fiscal years 2014 to 2019.

Instead of a per-gallon gasoline tax — which hadn’t been raised since 1986 — the bulk of Virginia’s transportation revenues now are tied to the wholesale gas tax. “The whole idea of indexing it to a percentage of the wholesale tax was the price of gas would rise, and that would index it to inflation,” Layne says. “Of course, it went exactly the other way.”

Oil prices fell. Fortunately, the legislation included a floor of $3.11 per gallon, so that taxes could only dip to a certain level. “If that floor wasn’t in, our revenues would be even down farther,” says Layne.

Still, the drop in oil prices and the elimination of an alternative fuel vehicle fee in 2014 have contributed to the reduction of revenues by $397 million over six years, according to December 2015 estimates from VDOT. Also, the Virginia legislation included revenue from the Marketplace Fairness Act, a federal online sales tax proposal that Congress never passed. In Virginia, that money would have gone mostly to transit funding. Without the revenue, a provision in HB2313 automatically increased the state gas tax by 1.6 percent, but that still did not fully make up for expected revenue from the Internet sales tax.

A federal highway bill, passed by Congress and signed into law by President Obama, will provide Virginia with approximately $96 million each year in additional federal transportation funds for the next five years. VDOT is awaiting details on the law’s implementation.

Inheriting the first significant influx of transportation revenues in decades, the McAuliffe administration and the General Assembly enacted legislation to ensure that available money is spent on projects that will have the most impact on the state’s transportation network.

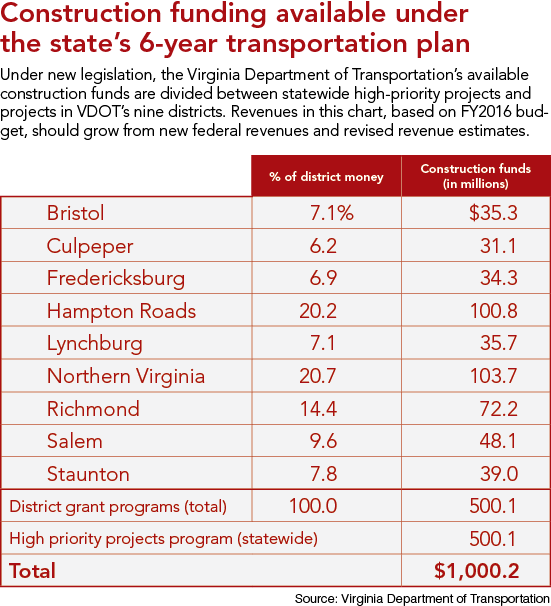

The remaining 55 percent of the construction money is divided (about $1.2 billion over the next six years), with half going to build statewide priority projects and the rest divided among the commonwealth’s nine transportation districts.

Decisions on how this money is spent are subject to another state law, HB2, which was designed to help the CTB score and prioritize projects.

The legislation uses six criteria — congestion, economic development, land use, safety, environmental quality and accessibility — to score projects that are submitted by regional transportation groups.

Competition is stiff. In this first round of HB2-driven projects, local authorities have submitted 288 projects costing more than $7 billion for about $1.2 billion available during the next six years.

The scoring on each project will be unveiled at the end of the month, although the CTB won’t officially decide which projects to include in its six-year plan until the spring. “The law says we must use [the scorecard], but it does not mandate that you pick the highest-scored projects. It does say if you don’t, you have to explain why you don’t use them,” says Layne.

This year will provide the first real test of how the new rules help the transportation board select which projects to fund. The Northern Virginia Transportation Alliance, an advocacy group for effective road and transit investments, has concerns about the complex regulations.

First, the alliance believes that traffic congestion relief should get a higher priority for scoring purposes. Currently, regulations say congestion relief should make up 45 percent of a project’s score in Northern Virginia. “What that says to the alliance is that everything else added together actually equals more than congestion relief, so is congestion relief really the greatest factor?” says Nancy Smith, policy director at the alliance, which advocates for a weighted score of 50 to 60 for congestion relief.

Smith says that the regulations also create a bottom-up approach that could limit the CTB’s abilities to put forward the most meaningful statewide projects. Under the regulations, the transportation board has limited itself to submitting only two projects for consideration for funding under HB2.

“Sometimes it’s hard for a local jurisdiction to think regionally because that’s not necessarily their job,” says Smith. “Key transportation investments really do need a statewide perspective.”

Regional authorities

The regional revenues set up by the 2013 transportation funding law are not governed by HB2 legislation. (Although it is significant to note that those regions still receive transportation spending from CTB’s statewide program.)

With less money to spend on statewide projects, the creation of regionally raised and dedicated transportation funds may have been the most effective legacy of the 2013 transportation spending bill.“When you have regions like Northern Virginia and Hampton Roads that have growing populations, growing economies and have a lot of needs already, that’s why it was even more important that HB2313 created these separate pots of money for these two regions,” says Smith.

In Northern Virginia, the authority has had a steady revenue stream. Its money comes from increases in local taxes that are not tied to gas prices, including a 0.7 percent local sales tax, a real estate grantor’s tax and a 2 percent hotel tax. Revenues generally have been in line with the expected $300 million each year.

The authority must give 30 percent of its revenues to Northern Virginia localities for their own transportation projects. The remaining 70 percent of the money is used by the authority for regionally significant projects. “We do take into account project readiness,” says Monica Backmon, executive director of the authority. “These are taxpayer dollars, and we want to make sure we’re advancing projects.”

So far, the $535 million has been allocated to a wide range of projects in various stages of planning and development. Some of the larger projects include Route 28 widening, Route 123 widening in Fairfax and construction of multimodal facilities during the extension of Metrorail’s Silver Line to Washington Dulles International Airport.

Now that the authority finally has money to spend, it has embarked on a two-year project to update its long-range plan. Upon completion in 2017, the plan will budget revenue for six years (2018 to 2023), working much like CTB’s six-year construction plan.

For its own dedicated revenues, the Hampton Roads Transportation Accountability Commission already has allocated $365 million, $15 million more than what has been collected so far, according to Kevin Page, the commission’s executive director.

That includes $257.6 million toward widening two of three segments of Interstate 64 from Newport News to near Williamsburg. The remaining money has been spent on preliminary engineering and environmental impact statements to help advance its nine mega-projects deemed vital to improving congestion in the region.

Hampton Roads’ regional revenues, which include a 0.7 percent increase in the sales tax rate and a 2.1 percent increase on gasoline with no floor in place, have been hurt by lower-than-expected oil prices. Revenues, anticipated under HB2313 to be more than $200 million per year for fiscal year 2016, are expected to be $43 million less than originally expected.

To build all of these mega-projects, the commission says it needs $229 million a year from other sources. It is exploring a variety of ways to do this, including significant investment from VDOT and introducing a floor on the regional gas tax. “It’s ambitious, but we have to unlock this region not only for our economic vitality but to enhance the quality of life for our citizens,” says Page. “It’s one that we feel we can achieve if we work together with our regional governments, Richmond and our constituency.”

A closer look at public-private deals

While Virginia has been changing the framework guiding transportation funding, the commonwealth also has faced criticism for some of its public-private partnerships (P3s).

Virginia’s Public-Private Transportation Act has been hailed as one of the country’s most forward-thinking laws allowing the public sector to use private dollars to help build expensive road projects.

But controversy has plagued many of Virginia’s P3 deals, including the $300 million spent to build an alternative to Route 460 before the proper permits were secured. (The project started as a P3, but eventually became a design-build project.)

Another controversial deal is the Elizabeth River Tunnels project, another P3 deal arranged under the McDonnell administration. Complaints about the project included the implementation of tolls before construction was completed and a contract provision that would require the state to compensate the private partner if the region built a competing crossing. “[This]deal is one of the worst deals I’ve ever seen negotiated,” says Gov. Terry McAuliffe. “We had to pay down the tolls by half. They were bad deals, plain and simple. Those deals would never happen in this administration.”

In response, last year the legislature passed measures to provide better oversight of P3 projects. The legislation established the Transportation Public-Private Partnership Advisory Committee, designed to determine whether funding each project as a P3 is in the public interest. The law also requires a responsible state agency executive, in most cases the transportation secretary, to certify with the governor and the General Assembly that the deal is in the public’s best interest. “I do believe that [the legislation] will go a long way to prevent what has happened in the past,” says Del. Chris Jones, R-Suffolk, who sponsored the legislation. “It’s a much more transparent process.”

Despite controversy over past deals, the McAuliffe administration is not abandoning the P3 process. VDOT announced in December that it would pursue widening Interstate 66 outside the Beltway as a P3 deal — the first that must adhere to new guidelines. The proposal would rebuild the interstate with three normal lanes and two “dynamic-tolling” lanes, where prices would fluctuate with traffic conditions.

Under the plan, public funding would not exceed $600 million, and the private partner would bear the financial risk if traffic volumes were lower than expected on the tolling lanes. The state is scheduled to select partners this year and retains the right to build the $2.1 billion project itself if agreements cannot be reached.

Going forward, Layne will be responsible for assuring the governor and the General Assembly that any proposed deal — and changes made to it — is in the best public interest. “That was a big issue with the Downtown/Midtown tunnel project [in Hampton Roads],” says Jones. “Some of the key details were not known until after the agreement was signed.”

This year’s legislation

This year will demonstrate how VDOT’s new framework will work as projects are scored and secured, so fewer bills on the transportation front are likely to be filed.

Jones plans to submit a bill, in consultation with the McAuliffe administration, that would help guide the state’s future decisions on using tolls. “We need to have some good policies on tolling,” says Layne. “One being that we can’t put a fixed toll on a project that doesn’t have an alternative, and two, no more tolling facilities until they have added a new capacity.”

Another piece of legislation, filed by Del. Jim LeMunyon, R-Chantilly, would prohibit tolling on I-66 inside the Beltway. The McAuliffe administration plans to add dynamic tolling during rush hour, an idea strongly opposed by many Northern Virginia motorists. The CTB has approved the I-66 plan.

McAuliffe’s proposed budget this year includes $338 million in additional construction money, but there seems to be little appetite in the General Assembly for any new designated revenues. That situation makes the new rules governing how money is spent all the more important.

But in Northern Virginia, where transportation has been a longtime headache, the new money has helped the region to begin addressing its transportation issues. Nohe, the chairman of the Northern Virginia Transportation Authority, says that the group determined in 2007 it would need $700 million a year to solve all of the region’s transportation problems.

“So in that regard, no, this is not the money that solves every transportation problem. The 2013 regional funds, however, do give us what we need to start solving the biggest problems,” he says.

“I often say: We will never solve every traffic problem in Northern Virginia, and those that we can solve will not happen overnight, but for the first time in over a generation, we at least have money to solve some of the problems, and that in and of itself is a revolutionary change.”

g