An ‘extroverted campus’

GMU is eager to be connected with Northern Virginia

M.J. McAteer //August 28, 2015//

An ‘extroverted campus’

GMU is eager to be connected with Northern Virginia

M.J. McAteer //August 28, 2015//

George Mason University does not believe in the ivory tower. The old image of a lofty institution of higher learning isolated from the practical realities of life is contrary to its mission. Its goal is to be not only a “comprehensive research university” but also “an innovative and inclusive academic community committed to creating a more just, free and prosperous world” — with emphasis, perhaps, on the “prosperous.”

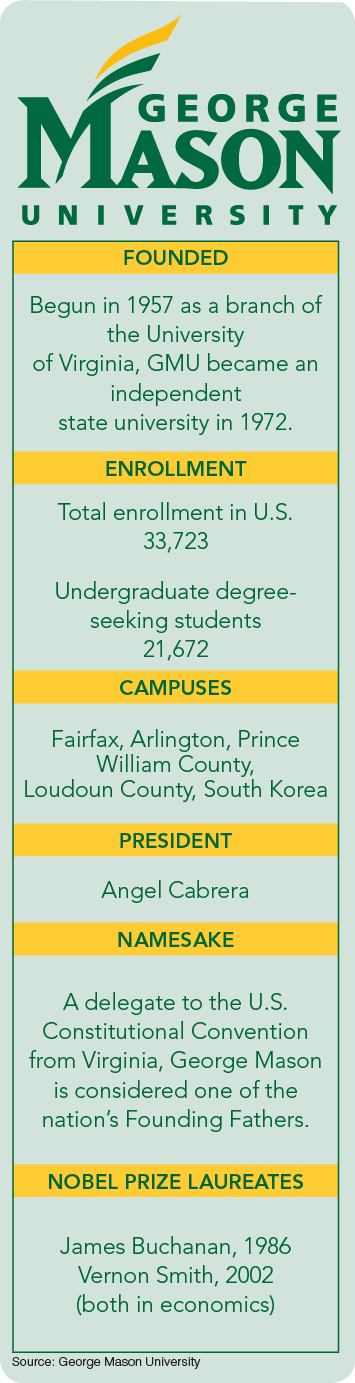

From its beginnings in 1957, as a branch of the University of Virginia with 17 students attending classes in a renovated elementary school in Arlington County, and its subsequent founding as an independent state university in 1972, GMU has transformed itself beyond recognition. It now has about 33,000 full- and part-time students — more than any other four-year public Virginia school — and campuses in Arlington, Fairfax, Loudoun and Prince William counties. Last year, GMU went international and opened a fifth campus in South Korea (see story).

Much of its remarkable expansion can be attributed to its adamantly outgoing attitude. “We are an extroverted campus,” says economist Stephen S. Fuller, director of the university’s Center for Regional Analysis. “The university set out to be connected to the various communities, and it uses the real world in the classroom.”

That connection has been mutually beneficial to Mason and Northern Virginia. In the latest available figures from a study done by Fuller’s center, the university had a $1.14 billion economic impact on Northern Virginia in fiscal year 2012 and employed the equivalent of 7,119 full-time workers. Indirectly that year, it produced another $440 million in economic activity and supported an additional 5,897 jobs. In Virginia overall, it had a $1.56 billion impact and was responsible for more than 16,000 jobs.

Two presidents

The university’s development is due largely to dynamic longtime presidents George W. Johnson (1978-1996) and Alan Merten (1996-2012). Both sought to entwine GMU with Northern Virginia’s economy by forging lasting partnerships with business leaders. Under the presidents’ consecutive tenures, the student body and the physical infrastructure of the university expanded. Mason, once considered a commuter school, became a well-regarded institution, no small feat for an upstart university.

The two presidents brought about these changes, in part, by pursuing A-list faculty. The university wasn’t shy about “stealing” talent from the likes of Harvard, MIT and Stanford, Fuller says. And these scholastic stars were willing to be recruited because GMU gave them freedom to pursue their interests. “[GMU] didn’t tell them what to do,” Fuller says. The university “took a facilitating approach and got out of their way.”

The university’s biggest gets included James M. Buchanan, a 1986 Nobel Prize winner in economics, and Vernon Smith, who would win the same award in 2002 after being recruited by GMU. Smith would go on to be an influential fellow at the Mercatus Center, the university’s free-market economic think tank in Arlington. That center’s raison d’etre is, not surprisingly, in perfect keeping with Mason’s overall mission: to narrow “the gap between academic ideas and real-world problems.”

Landing Northrop Grumman

Northern Virginia’s prosperity is driven by white-collar and high-tech companies and government contractors, including an enviable number of Fortune 500 corporations. Wu intends to further strengthen academic programs that best align with the needs of these businesses, with a special concentration on IT, the biosciences, law and economics. Cybersecurity also is a potentially huge market for Mason. Right now, positions in that field are going unfilled because companies can’t find qualified personnel.

Northrop Grumman’s decision to locate its headquarters in Fairfax County five years ago showed just how important the synergy between higher education and the local economy can be. In 2010, the corporate giant wanted to relocate to the East Coast, and it was being courted by a number of eager jurisdictions.

Gerald L. Gordon, president and CEO of the Fairfax Economic Development Authority, contacted GMU’s Merten for help in pleading the county’s case. Merten arranged for Wes Bush, Northrop Grumman’s CEO, to visit GMU so that he could see that the university could support the company’s recruitment needs.

The effect of the visit? “Enormous,” Gordon says. Northrop Grumman is now headquartered in Fairfax County near Falls Church.

Undoubtedly, thanks to Merten’s help, some Mason graduates now work for the giant defense contractor, which has 65,000 employees worldwide. Mason graduates, in general, do well in finding employment. Christine Cruzvergara, the assistant dean and deputy director for University Career Services, says that within six months of graduation, 74 percent of the class of 2014 had either snagged jobs, at an average annual starting salary of $40,000-$50,000, or were in grad school. More than 75 percent stayed in the metro area, a testament to how well their schooling fit the available job opportunities.

Fully half of Mason students are enrolled in graduate programs, an unusually high ratio compared with, say, the University of Virginia, where undergraduates outnumber graduate student by more than 2-1. That’s because so many GMU students are older — the average age is over 30 — and already working. Many return to school to “upskill” their credentials in order to stay current and advance in their fields. “The ability to process knowledge is rapidly changing,” Fuller says, and George Mason is there to help them keep pace.

SWAT team for businesses

Wu says his second priority for Mason is to reinforce its role as “a convener, an honest broker in pursuit of the greater good of the region.” Fuller calls it “being a SWAT team for local businesses.”

Since Cabrera became president, the university has stepped up its interactions with area businesses, interviewing CEOs and holding workshops with venture capitalists and other players in the Northern Virginia economy. The emphasis is on “what innovations are needed to fill the vacuum left by federal cuts and to develop entrepreneurship,” Wu says. The university’s last business forum drew 200 to 300 attendees.

Wu’s final priority is probably the most visible one of late: “to become an innovation and development engine for the region.”

To further that end, in April the university rebranded its Prince William campus as a science and technology center, and in conjunction with the name change opened the $40 million Institute for Advanced Biomedical Research on the campus.

The Mason Enterprise Center in the Fairfax campus has been helping to incubate a variety of businesses for years and now operates in several locations, and the new institute will play a parallel role for scientific startups.

Mason, in partnership with area hospitals and medical centers, intends for the institute to speed the development of medical devices and diagnostic and therapeutic procedures to the marketplace, Wu says.

Inova Health System is one such partner. “The economic benefit of joint investment is substantial,” says Brian Hays, director of the Inova Center for Personalized Medicine. “People don’t realize the extent of cooperation. It’s actually very broad, and we anticipate a giant increase in that relationship.”

The new biomedical research institute joins other advanced research facilities on the Prince William campus that focus on personalized medicine, including the Center for Applied Proteomics and Molecular Medicine and the Center for the Study of Genomic Liver Diseases. The campus is also the site of other high-tech research facilities such as the Serious Games Institute.

GMU’s Volgenau School of Engineering’s 6,000 students specialize not only in traditional fields such as civil and mechanical engineering, but in 21st-century technologies such as bio-engineering and cybersecurity.

“Engineers don’t just design cars anymore,” says Dean Kenneth Ball. Instead, they do cancer research using lasers and learn how to testify in court about computer fraud. “The old boundaries between disciplines are starting to become irrelevant,” he says.

Each of the school of engineering’s eight departments has an industrial advisory board to help shape curricula. Northrop Grumman, for example, was heavily involved in the creation of a new bachelor’s degree program in cybersecurity engineering, which began in January with 100 students. GMU offers 13 specialties in cybersecurity, and its Center for Secure Information Systems, the nation’s first such academic center, works on dozens of joint research projects with the Navy, the Marines, the Army and the Department of Defense.

“Having a university willing to embrace an entrepreneurial way of thinking can’t be underestimated or understated,” says Jeff Kaczmarek, executive director of the Prince William Department of Economic Development.

e