All about the Benjamins

Despite pandemic, Va. CEO pay was up in 2020

Ryan McKinnon //September 29, 2021//

All about the Benjamins

Despite pandemic, Va. CEO pay was up in 2020

Ryan McKinnon //September 29, 2021//

After a tumultuous and unpredictable pandemic year, the executives leading Virginia’s largest publicly traded companies still brought home sizable pay increases in 2020.

While median salaries for Virginia’s top CEOs were down 0.7% in 2020, and their median bonuses were down 10.6%, last year Virginia’s top executives saw a huge increase in pay coming from stock options, restricted stock and stock appreciation rights, according to Equilar Inc., a California-based corporate leadership data firm.

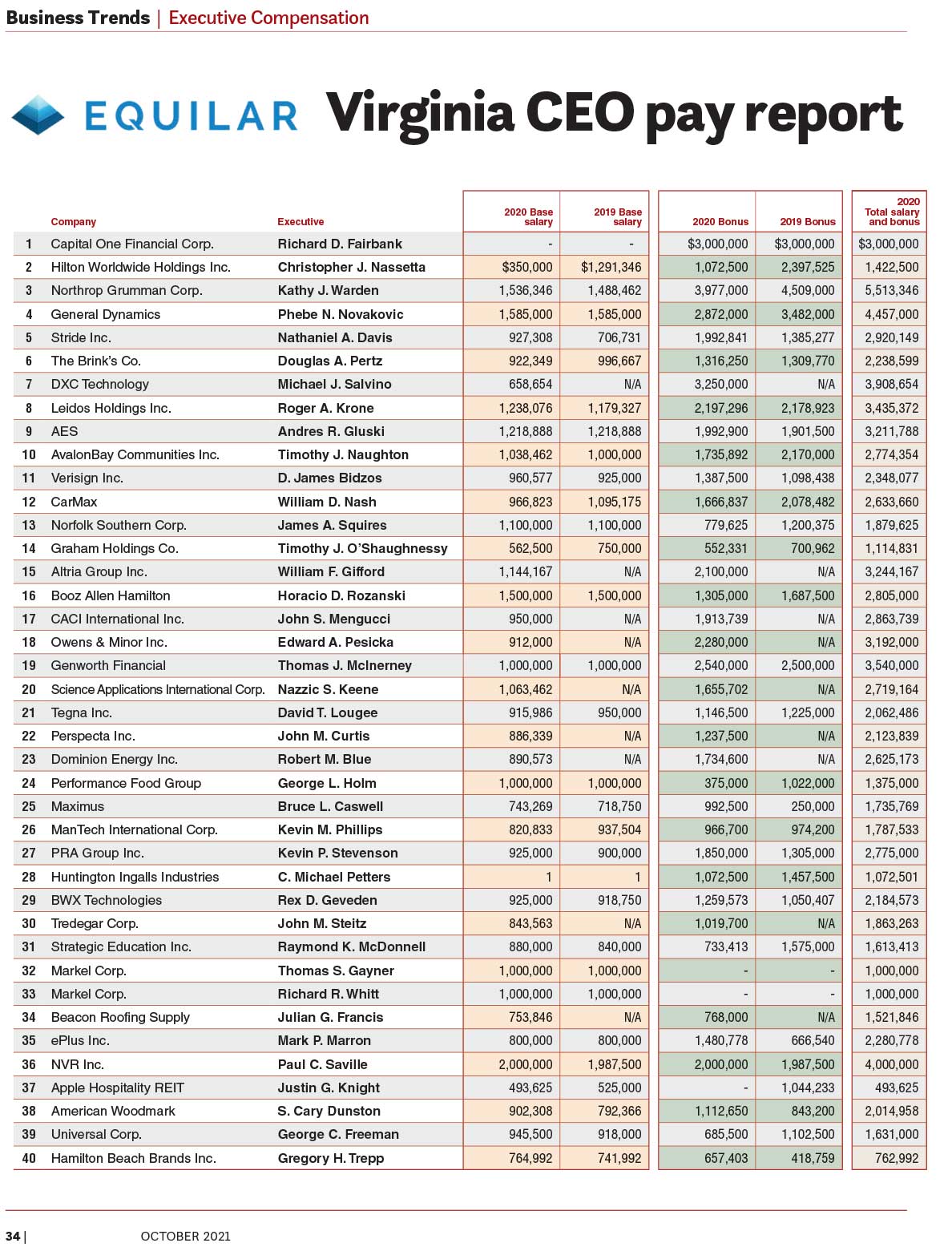

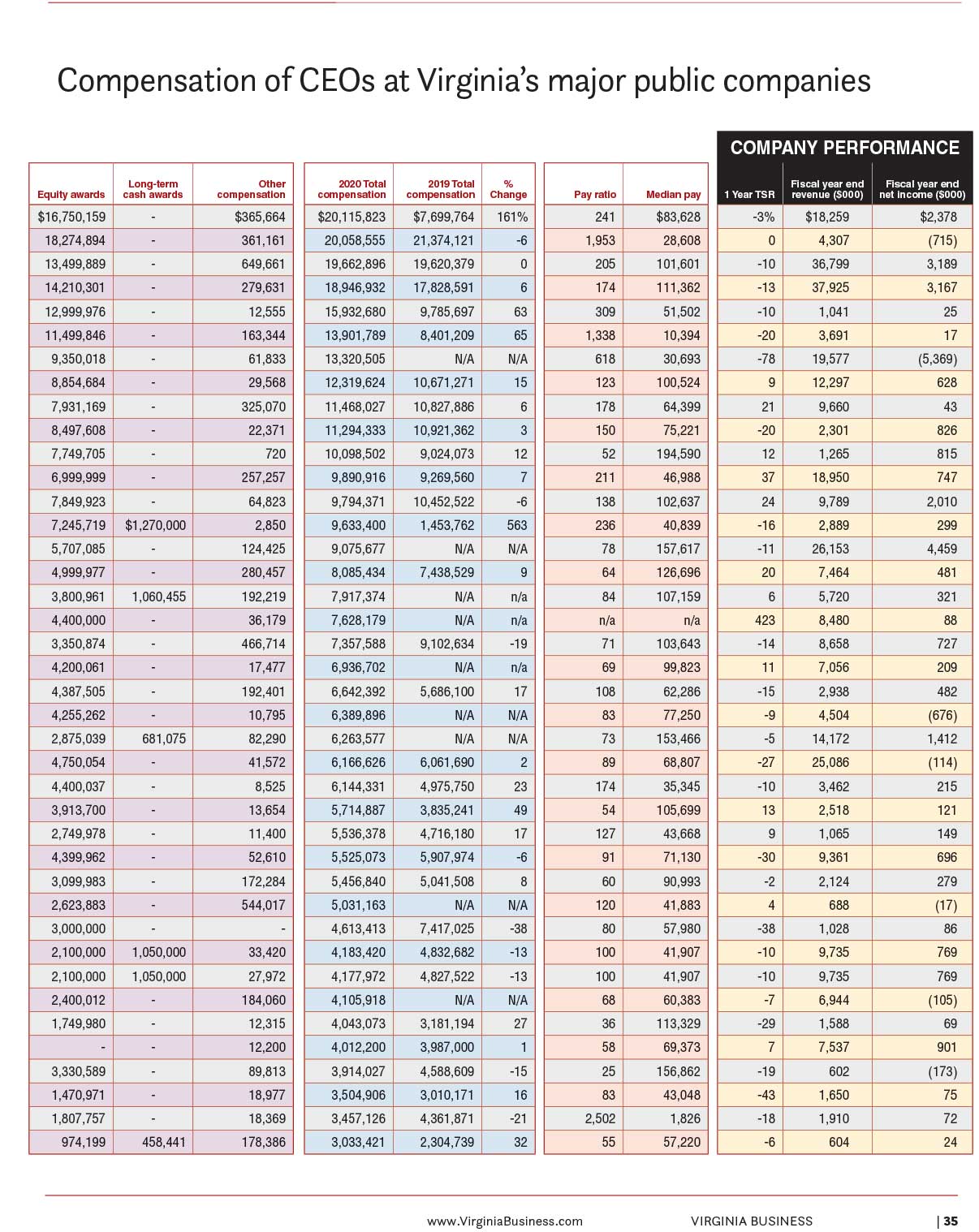

Equilar conducted Virginia Business’ most recent top executive pay report, examining the earnings of 50 CEOs from 49 public companies in Virginia with annual revenues of at least $1 billion. (See data for the top 40 highest-paid Virginia CEOs of publicly traded companies on Pages 32-33.)

Average equity payments for Virginia’s top executives were up 15.4% this year, bringing the average total compensation (including salary, bonuses and equity) of Virginia’s 50 highest-paid CEOs of public companies to $7.14 million, a 4.9% increase from 2019, when they brought home total compensation packages averaging $6.8 million.

Charlie Pontrelli, a senior project manager for Equilar, says the double-digit increase in median total compensation was higher than executives had seen in prior years, and it was partially linked to fortuitous timing.

Equity payouts (stock options, restricted stock, stock appreciation rights) are valued on a grant date, usually in February or March. Last year, that meant many CEOs were paid huge sums in equity during early 2020 because of 2019’s success.

“2019 was a great year, and equity grant sizes reflect what the company had been going through prior to COVID,” he says.

Decreases in salary and bonuses were to be expected in 2020, Pontrelli says. As the pandemic wreaked havoc on cash flow, many businesses cut executive salaries and bonuses.

“If you are uncertain about your cash flows, it made sense to preserve cash during a crisis,” Pontrelli says. “Bonus payments being lower makes sense because of a downturn in sales, and most likely companies were not meeting goals they had set out at the end of the year.”

Nevertheless, Virginia CEOs fared better with their compensation than CEOs nationwide last year, according to Equilar data. A similar study of executive compensation among the S&P 500 showed that median CEO pay (including salary, bonuses and equity) for those CEOs increased 5% in 2020, half the rate that Virginia’s business leaders enjoyed.

The top three earners among Virginia’s CEOs of public companies in 2020 were:

Richard D. Fairbank, chairman, president and CEO of McLean-based Capital One Financial Corp. His 2020 total compensation was $20.1 million, largely thanks to a $16.75 million equity payout.

Christopher J. Nassetta, president and CEO of McLean-based Hilton Worldwide Holdings Inc., demonstrated how equity payments can salvage a rough year. Nassetta’s salary and bonus were down 61% from the previous year, as the hotel industry took a COVID-19 beating. But his equity payment of more than $18 million earned him second place on the list, with total compensation of $20.06 million during a year when Hilton fell off the Fortune 500 due to its losses from the pandemic.

Kathy J. Warden, chairman, president and CEO of Northrop Grumman Corp., the Falls Church-based Fortune 500 defense contractor, ranked third on the list, with total compensation of $19.66 million.

Linking pay to ESG

Executives across the globe are under increasing pressure to do more than boost the bottom line, though.

More and more companies are linking CEO pay to meeting environmental, social and governance (ESG) objectives. These ESG

goals run the gamut, including improving a company’s safety record, expanding diversity among its workforce, reducing its environ-mental impact or improving employee compensation.

The one thing all ESG objectives have in common is recognizing that a company’s long-term value is more than just the total annual revenue.

This trend goes back more than 20 years, to when companies first began taking steps to be more environmentally friendly. But linking these nonmonetary outcomes to CEO pay is a newer development, says Don Lowman, a senior client partner with the global consulting firm Korn Ferry and a board member for the foundation of William & Mary’s Raymond A. Mason School of Business.

Lowman, who recently wrote a white paper on the topic, says that 44% of companies on the S&P 500 have at least one ESG objective linked to pay for at least one executive.

The bulk of bonus payments are still tied to financial performance, Pontrelli says, but executives who care about their end-of-year cash bonuses are being incentivized to give more than lip service to these nonfinancial goals.

And 2020 may have been the tipping point.

The COVID-19 pandemic, the racial justice protests following the police murder of Minneapolis resident George Floyd and increasing public concern over climate change have ramped up pressure on American corporate boards to focus on a variety of social goals, Lowman says.

“Boards have started to take this on as more of a priority. So many different stakeholders are putting pressure on companies around this,” says Lowman. “Some investors are making part of their criteria as to whether they invest in companies what kind of priorities they have surrounding ESG. There has just been a mounting pressure from a variety of constituents.”

Boards are increasingly making ESG metrics quantifiable, with executive compensation formulas factoring in achievements that had once been considered ideals to strive for, not hard targets to hit.

Executives in Virginia are no exception.

William Nash, president and CEO of Goochland County-based auto retailer CarMax, has a set of social responsibility objectives, including reducing the company’s carbon footprint and fostering the company’s long-term diversity and inclusion initiatives.

His goals are ambitious — reducing greenhouse gas emissions 50% by 2025 with a plan to achieve net-zero emissions across the company by 2050 in agreement with the Paris Climate Accords, according to a statement issued by the company.

At AvalonBay Communities Inc., the Arlington County-based real estate investment trust, 7.5% of Chairman and CEO Timothy Naughton’s 2020 bonus was based on the company’s score by GRESB, an independent organization that measures ESG performance for real estate companies and developers.

And Dominion Energy Inc. links 15% of Chair, President and CEO Robert Blue’s annual incentive plan to ESG outcomes.

Lowman says these types of arrangements aren’t just trying to appease activist investors or the public. There are long-term benefits to focusing on ESG objectives, but the return on investment may take years.

“[Companies think] the upside could be longer term. We’ll survive and sustain ourselves because our customers will think better of us [and] we’ll be able to attract and retain better talent, so over the long term this is going to add value to our enterprise even though in the near term this may cost us,” Lowman says, describing the mindset of boards that emphasize ESG goals.

Stephen P. Hills, former president and general manager of The Washington Post and an AvalonBay board member, recalls hearing conversations about environmental issues while leading The Post decades ago. The newspaper’s leadership team decided it was important, for both ethical and business reasons, he says, to take steps to reduce the company’s environmental impact.

Even though it has gotten increased attention in the past year, ESG isn’t the only factor that companies’ boards consider when determining CEO compensation packages, Lowman says. Firms also need to take into account other nonfinancial metrics that have a major impact on company’s success.

Take, for example, an airline, he says. On-time performance, efficient booking processes and customer satisfaction factor heavily into repeat business. All those nonfinancial metrics may be just as important to an airline’s board as goals such as improving diversity or reducing emissions.

“If they choose to carve out a nonfinancial metric like ESG, there are people in the organization who will say, ‘Wait a minute, we are putting too much emphasis on this one thing,’” Lowman says.

Another big question around ESG objectives is whether executives will take shortcuts to hit their marks. A CEO who wants to report higher average employee compensation could outsource the lowest-wage positions, for instance, or an executive who wants to improve equity could quickly bring on several employees from underrepresented groups, without really changing a company’s culture.

Hills and Lowman say those are risks with ESG objectives, and that’s why goals must be reasonable and executives need to be trustworthy.

“How do you provide the right incentives when the things we do now won’t even have any impact on the company for years to come?” Lowman says. “Study it carefully and consider both the anticipated benefits as well as the potential unintended consequences.”

Ultimately, it comes down to entrusting leadership to executives who see the long-term value in hitting these nonfinancial metrics.

“No system is a substitute for management,” says Hills, who is now the founding director of Georgetown Law’s Business Law Scholars program. “Almost any system can be gamed, so you have to trust your management team. You have to trust your CEO.”

Pay ratio

Regardless of whether a portion of CEO pay is linked to ESG goals, an executive’s total compensation can impact employee morale, says Jeffrey B. Arthur, an associate professor of management at Virginia Tech’s Pamplin College of Business.

“If a company is making a case to persuade employees that we are all in this together, and then the employees observe the executives getting big [pay] increases when employees aren’t, that inconsistency in messaging can impact perception of whether this company is following the guidelines they say they are,” Arthur says.

One of the metrics in Equilar’s analysis is pay ratio — total CEO compensation divided by the median pay of the rest of the company’s workers. Those numbers vary widely among the 50 Virginia public companies Equilar studied this year.

Verisign Inc., a Reston-based internet technology firm, has a median employee income of $194,590, ranking the highest for employee wages among the companies analyzed. Verisign’s pay ratio of 52 was also one of the lowest, meaning its employees earn closer to what the CEO makes when compared with the other 49 companies.

At the other end of the spectrum, Universal Corp., a global tobacco producer headquartered in Richmond, has a pay ratio of 2,502, and the median employee pay is $1,826 annually. But those types of disparities are to be expected, says Pontrelli, because Universal’s workforce is largely made up of seasonal part-time laborers, many working in developing countries. Verisign and other tech firms, on the other hand, are staffed by highly educated full-time workers.

“Pay ratio will vary a lot by industry,” Pontrelli says. “You typically have very low pay ratios in the tech sector with highly compensated full-time employees versus a business like Walmart, with mostly part-time workers.”

Average median annual pay for employees at Virginia’s 49 largest public companies this year increased as well, from $74,382 in 2019 to $79,125 in 2020, a 6.38% increase, according to figures from Equilar.

That could be a trend that changes in the coming year, Arthur says, as employees have increased leverage. Labor shortages, along with pandemic-related work expectations, have placed increased pressure on employers to boost wages.

“Wages have been relatively flat for a long time, and now it’s beginning to change,” Arthur says.

Capital-intensive industries, like manufacturing, are in the best position to boost wages in the coming year, he says.

But even if employees see an upward trend in take-home pay in 2021, they’ll still be keeping an eye on how the top boss’s pay raise compares to theirs.

“CEO pay gets headlines, and people pay attention to that,” Arthur says. “It’s public information, and so employees will react to what they see and what they hear.”

T