All aboard

Plan for high-speed rail from Richmond to Washington, D.C., is chugging along

Jack Cooksey //March 1, 2016//

All aboard

Plan for high-speed rail from Richmond to Washington, D.C., is chugging along

Jack Cooksey //March 1, 2016//

Seasoned rail commuters know to pack some patience for the trip from Richmond to Washington, D.C. On a good day, it’s a two-hour ride. On other days, with backups on the track, it can stretch to three hours or more. So, what about going point-to-point in 90 minutes?

That’s the promise of a transportation project designed to get high-speed rail moving in Virginia by 2025. In the meantime, Virginia is seeing the expansion of conventional passenger rail, a positive development hailed by economic development officials as a catalyst for tourism and new development.

Since 2014, the state’s Department of Rail and Public Transportation (DRPT) has been coordinating teams of engineers and planners whose goal is to significantly shorten travel times by train between Richmond and Washington.

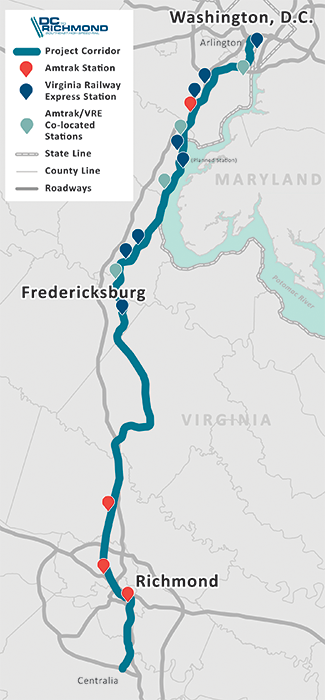

The DC2RVA Rail Project represents a 123-mile piece of the broader Southeast High Speed Rail vision that would eventually stretch to Florida. In Virginia, the aim is to reduce the Richmond-to-Washington travel time by enabling a top speed of 90 mph.

The DC2RVA Rail Project represents a 123-mile piece of the broader Southeast High Speed Rail vision that would eventually stretch to Florida. In Virginia, the aim is to reduce the Richmond-to-Washington travel time by enabling a top speed of 90 mph.

The intercity railroad tracks on the Richmond-to-D.C. corridor are owned by CSX Transportation and will need some work. For instance, design and engineering will help address the straightening of railway curves. Also critical will be construction of a third track — adding another lane to allow more trains in both directions.

“As far as Amtrak goes, our project is proposing going from 10 round trips a day to 18 round trips a day,” says DRPT’s Emily Stock, the DC2RVA project manager.

The push for high-speed rail began in 2002. That’s when the state’s rail agency, in coordination with North Carolina’s Department of Transportation, began a series of federally required studies — known as environmental impact statements — to gauge the feasibility of a high-speed corridor from Charlotte through Richmond to Washington.

“We’re really building on [the initial study], which gave us the direction to do incremental improvements to the existing railway and to stay within the existing CSX right-of-way as much as possible,” Stock says.

Now DRPT is working through a second phase of the impact studies that will become the basis of its final plan for the Federal Railway Administration’s (FRA) review and “record of decision,” Stock explains. If successful in that last step, Stock says, it “will allow us then to get funding for construction and final design and possible right-of-way acquisition.”

Previous reports, as far back as 2009, estimated the total cost to be $2 billion. Stock would not offer even a ballpark figure, except to say the final price tag would be in the “billions.”

Virginia taxpayers have a say, of course. DRPT presented its early findings and plans to the public in December 2015. At three open sessions — one each in Springfield, Fredericksburg and Richmond — Stock joined the agency’s engineers and consultants who discussed the project process face-to-face with attendees and helped them pore over maps showing possible railway options.

The months ahead will bring more data-digging for DRPT as the agency scrutinizes route options for various factors including ridership and revenue projections. Those options will be narrowed down to preferred alternatives, minding any natural or cultural resources that could be negatively affected. The sticky proposition of acquiring property to expand or reroute the right-of-way is likely to stir communities, when officials engage the public again before the final environmental impact statement goes to the FRA.

North Carolina’s piece of the Southeast rail project is well ahead of Virginia’s effort. In September, the FRA gave approval to its Raleigh-to-Richmond corridor. Now the Tar Heel state is trying to come up with the funding.

While Virginia’s DC2RVA project slowly chugs forward, conventional passenger rail services are seeing tangible, if incremental, growth and improvements.

Amtrak’s Norfolk-to-D.C. route, running just more than three years, quickly jumped in annual ridership, increasing from 127,937 passengers in 2013 to 153,857 in the 2015 fiscal year, according to Amtrak’s spokesperson Kimberly Woods.

The state rail agency committed about $11 million in funding to build a station in Norfolk, and then the city spent $3.7 million to build a shiny new depot in 2013.

Sarah Parker, assistant director of marketing in Norfolk’s development office, notes that a 23-story Hilton, at The Norfolk Main Hotel and Conference Center, might not have planted roots without the city’s prime landing spot — the convergence of Amtrak’s passenger service and light rail nearby. The hotel and convention center is scheduled for a March 2017 opening.

“Amtrak passenger rail has definitely magnified the attraction of investment in Norfolk,” Parker said by email, adding that the extension of service there “has been a huge leap forward for the entire region.”

In the western edge of the state, Roanoke is anticipating the scheduled 2017 extension of Amtrak service beyond Lynchburg.

Jill Loope, the Roanoke County economic development director, says that the growing promise of rail service there has not yet visibly spurred development, but local residents and businesses are anticipating its arrival.

“There’s a lot of buzz around the community,” Loope says. “Anytime you increase access, it translates into increased opportunity.” Another benefit? “Enhanced livability — that’s the piece of it that’s really attractive.”

Local governments around the state are hungry for the same promise and are seeking extensions of rail service in their localities, too.

For instance, officials in Blacksburg and the New River Valley have publicly suggested that Amtrak’s continued progress westward would help reduce traffic on Interstate 81, the highway feeding students back and forth from Virginia Tech and other schools in Southwest Virginia.

West of Lynchburg, in Bedford, members of a grass-roots group still hope to persuade the state to support an Amtrak station there. Two years ago, the group’s request for a train stop was answered with a rejection letter from state Secretary of Transportation Aubrey Layne.

Town Manager Charles Kolakowski says the grass-roots group appealed to the state again and was given a second chance contingent on data they could produce to show a significant demand beyond the town of 6,000 residents. “Our position is that this would benefit or serve a population of about 60,000 people … who would want to come here to visit for tourism and business purposes,” Kolakowski says.

Demand also appears to be on the rise for future extensions of the Virginia Railway Express (VRE), a public commuter rail service that links to the suburbs of Washington, D.C., and beyond. The service is jointly owned by Potomac -Rappahannock and Northern Virginia transportation commissions with two lines of transit from the west and south toward the nation’s capital. In November 2015, VRE extended south when it launched a new terminus in Spotsylvania County. More extensions could be in the works in years to come.

At least two other localities not connected to the 19-stop VRE now want on the bandwagon, says Bryan Jungwirth, director of public affairs and government relations.

VRE initiated a study last year to determine the feasibility of an 11-mile extension west from its Manassas line. “It’s a greatly expanding area as far as housing and employment,” Jungwirth says. “In general, that makes it a very attractive opportunity for an extension of the rail. It makes a lot of sense.”

Less likely to gain traction, he notes, is interest coming out of Caroline County for VRE to inch even closer to Richmond.

Despite the wait-and-see status of VRE’s future, the path to high-speed rail in Virginia is expected to see tangible progress sooner, not later. The state’s first segment of a third track — the extra lane needed for the Southeast High Speed Rail corridor — will be built by early 2017, under the terms of a $74.8 million Federal Railway Administration grant to DRPT and CSX Transportation, the state agency’s partner in the project.

Adding segments to the approximately 700 miles of track in the state seems like a straightforward strategy for increasing rail capacity so that DRPT can carry out the mission of faster, more frequent and more reliable trains — both for freight and passenger service.

It’s not always feasible or affordable, however, to expand rail, and this is where the term “network fluidity” becomes relevant, says DRPT’s Jeremy Latimer, a rail programs administrator.

Network fluidity describes a reality that many rail passengers may not recognize: Freight carriers like CSX and Norfolk Southern (which also own the tracks) depend on the same railways that transport people. So, state-managed track enhancements can prove just as effective and easier to achieve.

“Improving reliability has its own benefits, too,” Latimer says. “I mean, we’re looking at car-competitive Amtrak service, not necessarily just increasing the speeds.”