A wave of larger ships

Post-Panamax vessels are already here, and they’re changing the maritime industry

A wave of larger ships

Post-Panamax vessels are already here, and they’re changing the maritime industry

On a warm, calm morning in late July, Capt. Dave Culbertson steered his 93-foot tugboat alongside the massive Northern Javelin, a container ship longer than the Eiffel Tower is tall, as it neared the Port of Virginia’s marine terminals. The ship slid slowly though the Elizabeth River, traveling no more than 8 or 9 knots per hour to minimize the draft under its massive hull.

Culbertson’s tug, the Payton Grace Moran, and its sister tug, the George T. Moran, had been chosen to help dock the behemoth vessel at the Virginia International Gateway in Portsmouth, a Port of Virginia-operated marine terminal. These tugboats had a big job to do — pushing and pulling the ship to help the bridge team turn it 180 degrees in the Elizabeth River and dock at its assigned berth.

Culbertson’s calm demeanor reflected his 28-year career spent on tugboats, which are designed to help ships dock in all types of weather and conditions. As he guided his tug to his assigned position toward the stern of the ship, he handled several tasks at once: listening on the radio to instructions from the ship’s docking pilot, controlling the tension on the winch line attached to the huge vessel, navigating the channel and steering the ship against the strong pull of the Northern Javelin’s draft.

Although these tugs look like toy boats compared with the Northern Javelin, they are some of the largest and most technologically advanced tugboats available, capable of docking the largest ships in the world. Both boats, part of Moran Towing’s fleet, have 6,000-horsepower engines — more than 20 times the power of large SUVs. “Not many tugs around in the U.S. are bigger than this,” says Culbertson.

This is just one example of how the increased use of mammoth vessels is changing the maritime industry. From the increased precision required to steer these ships into port to the handling of their vast cargos, the effects of these larger vessels are rippling throughout the industry.

The Northern Javelin is a Post-Panamax vessel, the name for ships too large to travel through the Panama Canal. The port is now seeing visits from these massive ships almost daily.

While the ships strain the supply chain, they offer Virginia an opportunity to become a pre-eminent East Coast port. The shipping industry continues to use larger and larger ships, and other East Coast ports are rushing to match Virginia’s 50-foot-deep channel.

As the ships get larger, the maritime community is pushing forward with an initiative to dredge the channel to 55 feet — giving the port more leverage over others on the East Coast in handling these vessels when fully laden. “That’s the most significant thing for the Port of Virginia when you compare us with the U.S. East Coast ports,” says Art Moye, executive vice president of the Virginia Maritime Association. “It’s what will set this port apart from the other East Coast ports. It’s the game changer.”

The surge in larger ships

As ocean carriers look for greater economies of scale, container ships are getting bigger at a quickening pace. Today, the world’s largest ships can carry twice the number of containers that the big ships did just 10 years ago.

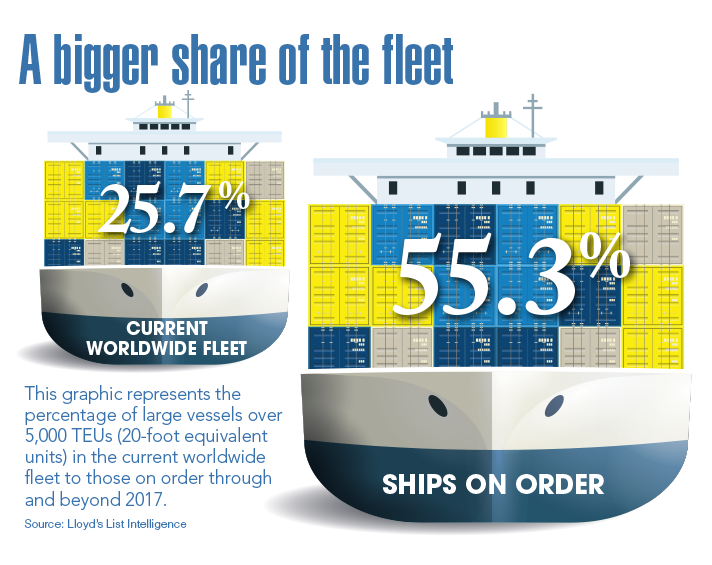

Ships larger than 5,000 TEUs — a vessel size that can fit through the Panama Canal — make up one-fourth of the worldwide container fleet, according to June stats from Lloyd’s List, a London-based maritime and shipping news journal. Nonetheless, these huge ships represent 59.7 percent of the total shipping cargo capacity — and even larger ships have been ordered. (A TEU is a standard shipping measurement that stands for 20-foot equivalent unit. Most shipping containers today are two TEUs.)

Lloyd’s stats showed that, of the container ships on order, 55.3 percent are bigger than 5,000 TEUs. (The largest ships in service now measure over 19,000 TEUs, which travel Asia-Europe service lines. None of the ships now visiting the U.S. approach that size.)

Leaders in Virginia’s maritime community anticipated the trend toward larger vessels, digging its channel deeper than any other East Coast port 10 years ago and adding modern cranes that could reach across these massive ships.

Post-Panamax vessels started visiting the East Coast three or four years before they were anticipated — and well before the completion of the Panama Canal expansion, which is scheduled to occur next year. Traveling through the Suez Canal, these ships carry containers between the East Coast and Asia.

Now vessels nearly 1,100 feet long, with the ability to carry 8,000 or 9,000 TEUs, are visiting the port almost daily. When fully laden, ships such as the MSC Bruxelles with a 9,700-TEU maximum capacity, require more than a 48-foot draft as they leave the port — getting pretty close to the channel’s 50-foot bottom.

And so, the maritime community is putting renewed efforts into a project to widen the Norfolk channel on the Elizabeth River, dredge the channel to 55 feet and dig the channel on the Southern Branch of the Elizabeth River to 45 feet.

The Port of Virginia and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Norfolk District have signed a cost-sharing agreement to study the benefits of the dredging projects. The Virginia Maritime Association hopes construction can begin on the project by 2020.

The Hampton Roads maritime community has had to adjust rapidly to the introduction of these big ships. For example, they require more precision in their handling and scheduling.

“They’re definitely a challenge,” says Capt. Bill Cofer, president of the Virginia Pilot Association. “The size of these vessels is such that our channels weren’t completely prepared for two-way navigation of these big ships.”

That means that the communication between the harbor pilots, docking pilots and port terminals has to be done well in advance. Any error in scheduling could end up blocking the shipping channel. “The coordination between the terminals and the pilots has got to be stronger than ever,” says Cofer.

The Hampton Roads’ harbor pilots climb aboard these ships at Cape Henry, where the Atlantic Ocean meets the Chesapeake Bay, and then guide them through the local waterways.

The steering of these ships is more difficult because of the amount of water being displaced, and therefore the ships must travel more slowly.

Before they reach their assigned berth at one of the marine terminals, ships are met by tugboats with docking pilots. They instruct the tugs in helping dock the ships.

The larger the ships, the tighter the turns, says docking pilot John Guess, who was assigned to dock the Northern Javelin. He notes that — while every job is different depending on the type of ship, the weather and the wind — the largest ships “[have] slowed everything down a little,” Guess says. “You can’t make a turn like you used to.”

Moran Towing, the owner of Payton Grace Moran and the George T. Moran, uses modern, clean-burning tugs to help move the big ships. “We’ve been seeing larger ships consistently for the last few years, and they’re going to get bigger still,” says Mark Vanty, vice president and general manager of Moran’s Virginia division. “We have the flexibility to respond to our customer demands.”

Experienced tugboat captains and docking pilots are essential to keeping ships from running into trouble while docking. These ships don’t operate like a car: They can’t stop or turn on the dime.

For example, a few weeks ago a small ski boat that had lost its power was anchored in the middle of the channel overnight. It took last-minute maneuvering by the pilots and the tugs to avoid the boat.

Once docked, the effects of these big ships also are felt on shore.

With more boxes on board a ship, it takes longer for longshoremen to load or discharge them. “The bigger ships mean longer hours,” says George Brown, president and CEO of CP&O, a stevedore at the port terminals.

Previously, longshoreman could work a vessel in nine to 10 hours. Today’s larger ships can require anywhere from 15 to 24 hours to work, says Brown.

Longshoremen’s average workday is 10 hours, but if a vessel requires 15 hours, they often stay to finish the job.

More cargo at terminals means ample opportunities for work. “People can get up to 70 or 80 hours of work a week if they want to work outside of their own gang,” says Brown.

About six or eight months ago, the maritime industry had to add more than 200 longshoremen to handle the increased cargo traffic.

Terminal congestion earlier this year sometimes left truckers with eight-hour waits to drop off or collect cargo. That situation, however, was caused more by an influx of cargo rather than the introduction of the larger vessels, port officials say. In fiscal year 2015, the Port of Virginia’s cargo volume grew 8.9 percent to a record 2.5 million TEUs.

The West Coast, however, has seen delays because of the visits of mammoth vessels that haven’t yet visited the Port of Virginia. Some of these ships require a week of work by longshoremen before they could leave port.

“There have been a lot of issues impacting congestion,” says Katie Carney, director, international and customs compliance in Livingston International’s Norfolk office. “Larger vessels, vessel bunching and equipment imbalance. The East Coast took on additional vessels from the West Coast coupled by some larger vessels that impacted the congestion on the East Coast. I do not think our infrastructure is prepared to take on this additional work.”

This past winter, the Port of Virginia terminals were especially congested because of labor disputes on the West Coast and a snowy winter in the East that closed the Virginia port for several days. But the West Coast’s issues could be a warning sign for the Virginia port.

The port has taken a number of steps to try to avoid tie-ups, including the purchase of additional equipment, tweaks to operations and the reopening of Portsmouth Marine Terminal to container traffic. “The vessels are getting bigger, and more and more are taking advantage of Virginia’s deep water,” says port spokesman Joe Harris. “So we are assessing all areas of our operation to ensure that we are prepared for volume increases that will be brought by a number of factors.”

Better planning

The effects of larger vessels are making freight forwarders busier than ever.

The larger ships require companies handling the logistics of international shipping to begin their planning earlier, track shipments more closely and often scramble to find an available motor carrier.

“We really are doing our planning much earlier than we used to,” says Carney. “There’s a lot more communication. It takes a lot more staff to do this work, a lot more talented staff.”

The larger ships, coupled with shipping alliances that allow ocean carriers to use each other’s vessels on certain trade routes, make planning more difficult for manufacturers. Their shipments may end up bunched together rather than spread out, affecting trucking schedules as well. “That becomes a logistics problem also down the road because then you have importers and shippers that tend to get everything on one vessel instead of getting everything spread out,” says Carney.

The increased cargo volumes at ports also are making it more difficult for shippers and motor carriers to avoid detention fees and demurrage charges — which are charged for having a shipping container out too long or on a port terminal.

Some of the shipping lines have begun to charge as much as $175 to $275 per day. Demurrage charges and detention fees have been so high that the Federal Maritime Commission is investigating them.

To handle larger ships, O’Callaghan says, the schedules of truck drivers, warehouses and distribution facilities should match the maritime community’s 24-hour routine. “With that vessel being in the port longer, it’s going to require people to change their behavior in work days. We need the warehouse and distribution facilities to adjust to the timing to coincide with the operation of these big ships.” O’Callaghan adds this already is the practice on the West Coast.

He notes that his drivers are starting to see improvements at Virginia’s marine terminals because of recent equipment purchases, but he believes new procedures and operations now in place will be tested when volume likely picks up this fall.

Jeffrey Heller, vice president of intermodal and automotive of Norfolk Southern Corp., agrees. He says the railroad wants containers to get from ship to train in less than 24 hours. “It’s not as easy as it sounds,” says Heller. “The matter of fact is that, as the business grows, the port will need to ramp up and lift more boxes in a 24-hour time period. I think we’re going to get tested this fall.”

Rail freight continues to grow for Norfolk Southern, which along with CSX Corp. is one of the two primary railroads serving the Port of Virginia’s terminals. In 2010, the railroad completed The Heartland Corridor, which raised tunnels and removed other obstacles along a route to the Midwest, cutting off 250 miles for double-stacked container trains to reach Chicago.

“The good news is [the Heartland Corridor] is really being tested,” says Heller. Norfolk Southern serves both Norfolk International Terminals and Virginia International Gateway in Portsmouth. Freight in Virginia is up 3.5 percent over last year, and much of that comes from traffic along the Heartland Corridor, he says.

Opportunity amid growing pains

Despite its ripple effects through the supply chain, the larger ships present an opportunity for Virginia. Virginia is the only East Coast port with authorization to dredge to 55 feet.

The largest ships visiting the Port of Virginia today are about 9,700 TEUs, and port officials expect to see 12,500-TEU ships in a year. But local maritime experts don’t expect next year’s completion of the Panama Canal’s expansion to bring a bonanza of larger ships.

A more significant event for Virginia could be the raising of the Bayonne Bridge at the Port of New York, which is scheduled to be completed in 2017. “At that point the carriers could employ even larger ships for the U.S. East Coast,” says Moye of the Virginia Maritime Association. “They’re not going to put a ship in service just for Norfolk.”

And as these ships continue to get larger, at 55 feet, Virginia could be the only port able to accommodate these massive ships when fully laden.

As it moves through its current growing pains the port has the potential to be a major East Coast player in international trade.

“What the 55 feet allows Virginia to do,” says Cofer of the Pilot Association, “is to be the only Port of Virginia on the East Coast of the United States that can bring in the global fleets, not just of today, but clearly the future will be these gigantic ships.”