A rising tide?

Panama Canal expansion could change the game for Port of Virginia

A rising tide?

Panama Canal expansion could change the game for Port of Virginia

Next year, all of Virginia’s harbor pilots will undergo specialized training in Louisiana. The purpose behind the out-of-state trip is to gain skills in handling the next class of immense ships expected to visit Hampton Roads’ ports.

These mammoth ships, seven feet wider than a football field and nearly as long as the Empire State Building is high, are capable of handling 40 percent more cargo than the largest container ships now calling on the Hampton Roads harbor.

“[These training centers] have scaled-down models like the real ship,” says Bill Cofer, president of the Virginia Pilot Association. “The pilots actually practice on a lake that has a contour very similar to our actual port, so it simulates how the ship would react in the channels.”

Harbor pilots, who guide commercial ships from the Atlantic Ocean through the region’s channels, undergo extensive training and continuing education to ensure they can safely navigate these massive vessels through Hampton Roads’ harbors.

Cofer thought the harbor’s 45 pilots wouldn’t need additional training for three or four years. Yet now he’s fielding calls from shipping lines who say Virginia’s ports could see ships with a cargo capacity as large as 14,000 twenty-foot equivalent units, known as TEUs, as soon as late 2017 or 2018. Today the largest ships visiting the port can carry about 10,000 TEUs. (TEUs are a standard size in containerized shipping. Two TEUs is the equivalent of about one normal truckload.)

“When we were preparing for 8,000 and 10,000-TEU ships to visit the port, everyone told us they wouldn’t come to Virginia and they did,” says Cofer. “Now we’re hearing the same thing about 14,000-TEU ships. And we know they’re coming because the shipping lines are asking us about bringing them.”

In late June, the long-awaited Panama Canal expansion officially opened with much fanfare. The $5.4 billion project expanded the locks of the canal and added a third lane, tripling the size of the container ships that can pass through its locks.

Now, 14,000-TEU ships can use the canal, and some industry experts think that could mean bigger ships and more cargo are headed for the East Coast.

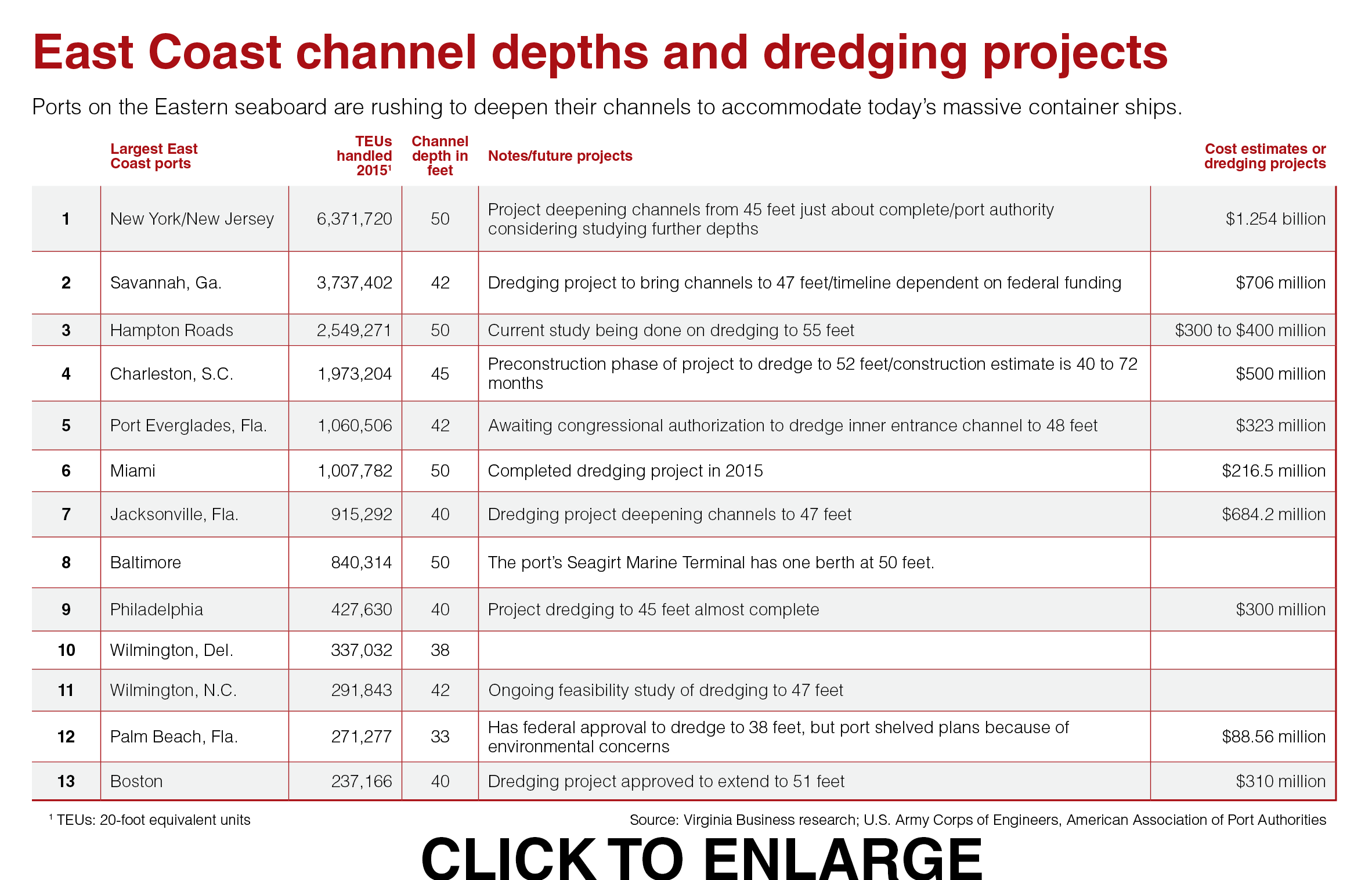

Ports along the Eastern seaboard have spent millions preparing their channels and infrastructure to handle the larger ships that would traverse the canal. In a horse race among the ports, Virginia lost its edge as the deepest on the East Coast. It is now tied with ports in New York, Miami and Baltimore, which offers a 50-foot depth at one berth. Charleston is in the early stages of a project to dredge its channels to 52 feet.

But the shipping industry is heavily in flux, leaving experts guessing whether the expanded canal will have the impact anticipated by East Coast ports. Shipping capacity continues to outpace demand, and shipping lines are merging and creating alliances in an effort to save money.

In Virginia, port officials have long believed that the canal’s widening would not suddenly bring a flood of new, larger ships. In fact, many big ships already are calling on Virginia’s marine terminals, traveling from Asia through the Suez Canal.

Nonetheless, many signs — like the shipping lines contacting the pilots — now point to a positive, long-term effect in Virginia from the canal’s expansion, particularly when international trade rebounds.

In preparation, Virginia is expanding its terminals, working on landside improvements and studying whether to dredge its channels another five feet — again giving it the distinction as the deepest port on the East Coast.

“Every port on the East Coast will take a certain degree of traffic from the Panama Canal, but the question of how much is very much up to the discretion of individual ports that are really in a good position to increase their competitiveness,” says Peter Ulrich, a managing director and partner with The Boston Consulting Group. It conducted a study showing East Coast ports likely would benefit from an expanded Panama Canal.

It looks like even bigger ships are coming. Is Virginia ready?

Short-term shift/long-term gain

Just two weeks after the Panama Canal expansion opened, Virginia saw the largest ship ever to reach its terminals. Mitsui O.S.K. Lines Ltd. launched the first Neo-Panamax vessel to transit the expanded canal in a new service rotation connecting ports in China and South Korea with New York, Norfolk and Savannah.

“We have been handling the larger ships for quite some time, those that have transited through the Suez Canal,” says Art Moye, executive vice president of the Virginia Maritime Association. “The expanded Panama Canal opens up additional opportunities because some of the carriers will find an all-water service to the East Coast could be more economical than … calling on the West Coast and having the East Coast cargo [transported by rail].

“It definitely opens up opportunities for us, but I think a lot of people were anticipating a huge tidal wave of cargo and ships on the day it opened,” says Moye.

The global container industry has been facing sluggish growth, and so East Coast ports are unlikely to see a huge short-term surge. The Port of Virginia itself saw only a 1.1 percent growth in the number of TEUs it handled in the first seven months of 2016, a drop from the 10 percent growth it saw the previous year.

In the short-term, there are signs the expanded canal is shifting trade patterns.

Maersk Line, the world’s biggest shipping line, already has shifted one of its services visiting the East Coast ports of Newark, Norfolk and Baltimore through the Panama Canal. The change will shorten transit times between the East Coast and Far East Asia, possibly by close to a week, according to the Journal of Commerce. The service, however, already was visiting the Port of Virginia.

In addition, more shippers are using the Panama Canal for its all-water routes between Asia and the U.S. — and that could be a good sign for the future of East Coast ports. In July, the Panama Canal already was the leading route for all-water container services between the Far East and the East Coast, capturing 57 percent of the market share, according to maritime industry analyst Alphaliner, compared with 48 percent at the beginning of the year.

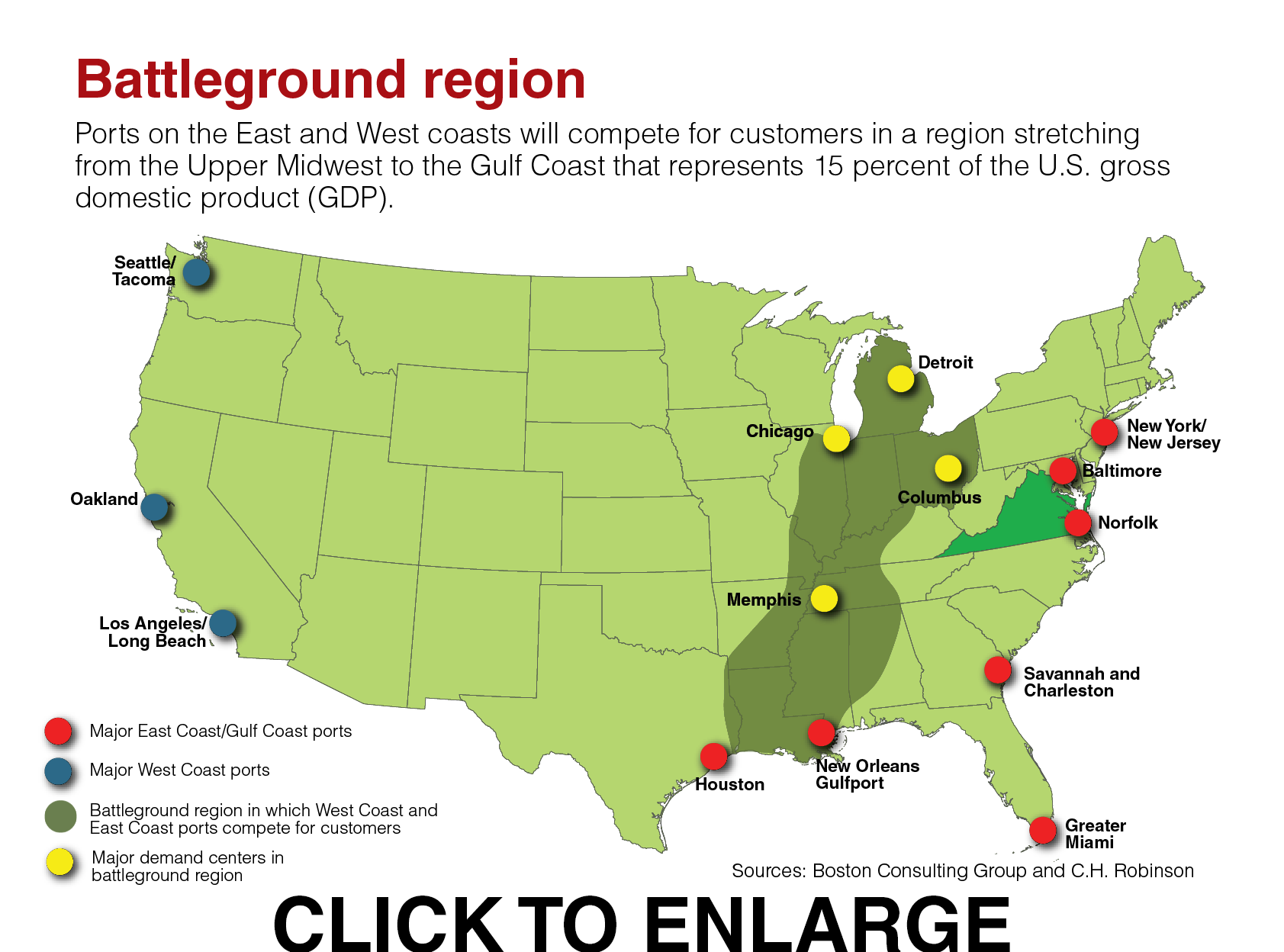

Long term, the expanded Panama Canal could have a profound impact on East Coast ports, according to a 2015 study by The Boston Consulting Group and the transportation company C.H. Robinson. The study found that the expanded canal could shift as much as 10 percent of container traffic between East Asia and the U.S. from West Coast to East Coast ports by 2020. A shift of that size would be double the cargo volume the ports of Savannah and Charleston are handling now, the study points out.

The study found the three ports most likely to see a positive effect are the biggest on the East Coast: New York, Georgia and Virginia. And as shipping lines move to larger and larger ships, ports with deep channels, such as Virginia, should benefit in the long run.

Also important for Virginia, the study concluded that “the battleground on which U.S. ports compete with one another for customers will likely expand and move several hundred miles west, toward Chicago and Memphis.”

That’s a key advantage for Virginia, which competes mostly on its rail connections with the Midwest since the population in its direct market, Hampton Roads, is smaller than many of its East Coast rivals.

“We have extraordinarily good rail service,” says John Milliken, chairman of the Virginia Port Authority Board of Commissioners. “We have the largest proportion of our product moving by rail of any other port on the East Coast, and that’s a good thing.”

Virginia could see another big break once the raising of the Bayonne Bridge is completed by the end of next year. The bridge, which connects Bayonne, N.J., and Staten Island, currently blocks some big ships from visiting the Port of New York/New Jersey’s busiest terminals. Most shipping rotations visit multiple ports on the East Coast, particularly the populous New York region, so raising the bridge could create new opportunities for Virginia.

“One of the hang-ups, of course, is the Bayonne Bridge still needs to be raised,” says Mike Coleman, president of CV International, a freight forwarder based in Norfolk.

Coleman predicts carriers will deploy larger ships to the East Coast in a slow, methodical shift. “The carriers are going to continue to move toward larger ships,” says Coleman. “They need to. The bigger the vessel, the lower the [transportation] cost for each container, and they need to find ways to reduce costs.

“It’s not going to happen overnight. I think the carriers are going to be very pragmatic in the deployment of these larger vessels.”

Virginia prepares

Virginia faces the same difficulties confronting most ports today — congestion at the terminals and on the surrounding roads. Bigger ships dump a larger number of containers at terminals at one time.

To prepare for growth, the commonwealth is making a historic investment in the port. The General Assembly and Gov. Terry McAuliffe agreed this year to issue $350 million in bonds to pay for a major expansion at Norfolk International Terminals (NIT), the port’s largest terminal. The expansion will increase NIT’s capacity by 46 percent. “In recent years, we had not maintained a level of investment in our facilities that we should have, and this sends a message to the global shipping world that Virginia is definitely serious about being a major player as far as East Coast ports are concerned,” says Moye with the Virginia Maritime Association.

Construction is expected to begin on the three-year project this fall, which will allow container stacks at NIT to be higher and denser.

The port also is planning to expand the privately owned Virginia International Gateway (VIG) terminal in Portsmouth, which it currently leases. VIG and the port are involved in ongoing negotiations to lengthen the port’s lease of the terminal. “It’s quite a complicated deal when you’re talking about a major change in the lease terms and a significant, roughly $320 million new investment by the private owners,” says Milliken. “We’ve agreed on an overall term sheet, but like most major economic business deals, there are details that one has to work through, and we’re not quite there yet.”

Another congestion relief project is construction of a new gate complex. It will provide 26 new lanes, doubling the gate capacity at NIT. The complex is scheduled to open this fall, and will eventually tie into an Interstate 564 connector, keeping trucks off the frequently busy Hampton Boulevard in Norfolk.

Motor carriers have advocated a gate complex at the port’s north end for years, says Frank Borum, president of Tidewater Motor Truck Association. The project “should help eliminate bottlenecks at this main gate when trucks back up. It’s definitely going to help, but there’s still a question of whether or not it will help during rush hour.”

Another challenge is ensuring trucks can move containers from the terminals efficiently. Hampton Roads, an area that has long been plagued with traffic congestion, finally has received regionally dedicated transportation money under a new state law. The Virginia Department of Transportation has begun a number of projects in the region, including expansion of Interstate 64 on the Peninsula.

VDOT in early August released an environmental impact study and cost estimates for plans for four water crossings. Creating an additional water crossing is seen as vital to tackling the region’s traffic problems. “As far as the competitiveness of the port, I think we’re positioned pretty well, but we just need to work on our infrastructure around the harbor,” says Borum. “I think it will be good for the port if they will be able to increase volumes 46 percent at NIT, but you’ve got to have the roads and rail to get it out of the port.”

The port is exploring new ways to move cargo out of its terminals. Earlier this year, the port signed a 40-year lease at the Port of Richmond — now called Richmond Marine Terminal. The port also is making investments in the river terminal and has expanded the barges hauling containers from Hampton Roads to Richmond.

The port is pitching the Richmond terminal’s advantages to overseas shipping lines. The facility reduces “some of the surface transportation uncertainties of coming out of Hampton Roads [such as traffic jams],” says Milliken. “That will be of growing importance.”

The port authority also is considering additional river terminals or inland ports, such as its intermodal transfer facility in Front Royal.

Perhaps the most significant undertaking includes plans to dredge the Port of Virginia’s main channels to 55 feet.

That depth would give Virginia an edge over other East Coast ports, officials say. Not only would the project allow Virginia to reclaim the status of being the deepest port on the East Coast, but it also would be more likely to be chosen as a “first-in” or “last out,” port, because it could handle massive ships when they are fully laden. “The deeper you are in the channel, the more likely you are to get the heavily laden ships,” says Milliken. “If you’re the first or last port of call, [the ship sits] lower because [it has] more cargo.”

The project also would widen part of the channel to about 1,400 feet at certain places to ensure the port maintains two-way navigation. “It definitely is a game changer for our port from our standpoint,” Moye says of the project.

Dredging to 55 feet and widening the channel would help Virginia ensure it could handle the next class of ships. The channel mostly would need to be widened along a 6- to 8-mile stretch from the Chesapeake Bay-Bridge Tunnel to Thimble Shoal Light, a lighthouse in the Chesapeake Bay. “We’ve done a lot of simulation on the next class of ships,” says Cofer. “The 14,000-TEU ships will require one-way navigation at that stretch because simulations have shown the interaction of ships to be problematic. It’s challenging, but it’s the prudent thing to do to protect the waters of the commonwealth.”

A potential bottleneck could hinder schedules at the busy port, which also hosts naval vessels and a wide variety of non-containerized cargo. Virginia’s channels actually compare well with other East Coat ports, whose channels are shallower or narrower. “We’re sharing these issues because these ships are so mammoth,” says Cofer.

The port received congressional authorization in 1986 to dredge its channels to 55 feet. At first, however, only the outbound channel was dredged to 50 feet because of budgetary concerns. That project was primarily done to accommodate massive coal exports from Virginia harbors. At that time, the largest container ships in the world carried 3,000 to 4,000 TEUs. The inbound channel eventually was dredged in the mid-2000s to accommodate the growing size of container ships.

Now the Port of Virginia and the Norfolk District of the Army Corps of Engineers are jointly paying $3 million to re-evaluate the economics and engineering aspects of dredging to 55 feet. The study should be completed in June 2018.

Under the study, the corps will analyze whether the channel could be dredged even further, says Richard Klein, program manager at the Army Corps of Engineers. “We’re looking at the economics and benefits of dredging incrementally from 54 to 58 feet,” says Klein.

Dredging the main channel is estimated to cost $300 million to $400 million, a cost that would be shared equally by the state and the federal government. The project timeline would include about two years for engineering and three to five years for construction, according to Klein. But the timeline also would be dependent on congressional funding.

Cofer says it makes sense for the federal government to invest in dredging at the Port of Virginia. “If you’re doing an objective comparison to all the other ports, our dredging needs and dredging costs are much less,” says Cofer. “In New York, you’re blasting rock … In Hampton Roads you’ve got good clean sediment, and it’s relatively inexpensive compared to everywhere else.”

A potential ‘gold mine’

An important — but less publicized — part of the dredging project includes efforts to dredge the Southern Branch of the Elizabeth River.

The port and the Corps of Engineers are spending another $3 million to study efforts to dredge part of the Southern Branch from 40 feet to 45 feet and other areas from 35 feet to 40 feet. The project would cost between $150 million to $200 million. Because of its depths, under the Water Resources Act, the federal government would be responsible for 65 percent of the funding.

The Southern Branch is home to the port’s Portsmouth Marine Terminal — reopened to container traffic last year to help manage congestion — but mostly includes private terminals. These facilities move commodities mostly through bulk — not containerized — cargo. The commodities they handle include wood pellets, grain, salt, minerals and aluminum sulfate.

Like container ships, the size of bulk-cargo ships also are growing, so more channel depth would help these terminals. “There are many bigger ships out there that could use the additional draft on the Southern Branch,” says David Host, chairman and CEO of T. Parker Host, which serves as the agent for many ships serving terminals on the Southern Branch. “The more cargo you can put on that ship, the cheaper the freight rate is. You’re going to be more competitive, selling grain or wood pellets for less.”

In addition, the new depths could attract new investment. “I think the Southern Branch is the gold mine of the port for everything else other than coal and containers,” says Host. “And there’s room for expansion for somebody to come in and make an investment. It’s going to be a lot more attractive if you have 5 feet more of water depending on where you are on the river.”

So far, Virginia’s channel depths haven’t given it a major edge over its East Coast competitors. For example, the ships in the same rotation as the MOL Benefactor also are visiting Savannah, where port depth now is only 42 feet.

Cofer, however, points out that a few years ago, large ships were coming in almost full, requiring a draft of 49 feet and three inches of water. That means, he says, going deeper will help the port keep up with the growing size of container ships.

“If you look at the global fleet, and what’s being built in the shipyards around the world, this is the future,” says Cofer. “This is going to be transitioning the ports of the world.

“I really believe when we look back in 10 or 15 years, we are going to recognize that we were living through this period that was unlike anything we’ve seen in recent history with the explosion of the size of ships and the maritime community trying to respond to it.”

l