A larger rotunda

Entering its third century, U.Va. recruits more first-generation students

A larger rotunda

Entering its third century, U.Va. recruits more first-generation students

Alita Robinson, a second-year University of Virginia student from Delaware, delivers a personal message when she calls potential donors seeking support for financial aid programs.

“I always tell people the only reason I’m at U.Va. and have these opportunities … is because I got a scholarship,” says Robinson, who plans to study educational policies and their impact on minority youth.

Robinson is one of nearly 2,040 undergraduates at U.Va. this academic year who are classified as first-generation college students, meaning neither parent graduated from a four-year college or university.

They’re a group that is the focus of heightened attention and support, and not just because the university’s president, James E. Ryan, shares their background.

From farm kid to billionaire

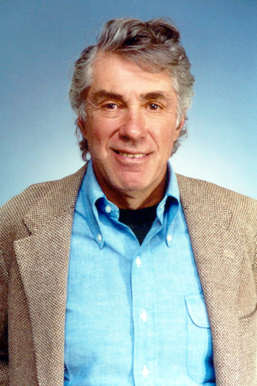

In October 2019, U.Va. announced a $100 million donation — primarily to support first-generation students — from New York billionaire real estate developer David Walentas, a 1961 graduate who found his way to Mr. Jefferson’s university from a farm in upstate New York with the help of a scholarship.

“Attending U.Va. was a transformational experience for me and helped lay the foundation for the rest of my life,” says Walentas, who made the gift with his wife, Jane. “College opened a lot of doors I didn’t know existed and exposed me to tremendous educators and ambitious students — a monumental step from working on a farm as a kid.”

Walentas, also a 1964 graduate of U.Va.’s Darden School of Business, founded the real estate development company Two Trees Management in 1968. Two Trees is credited with transforming the Brooklyn neighborhood known as DUMBO — short for Down Under the Manhattan Bridge Overpass — into a popular destination.

Of his gift, $75 million will be used for scholarships and fellowships for first-generation students, and $25 million will finance fellowships and professorships through the Jefferson Scholars Foundation and Darden.

The university announced its $5 billion “Honor the Future” campaign, which also recognized the university’s 2019 bicentennial, in June 2018.

“After 200 years of serving this community and this country, it’s important to ask what comes next for the University of Virginia,” Ryan said at the time. “The answer is that there is no limit to the good that this institution can do for others. This campaign plays a critical role in allowing us to pursue these ambitions together, and I am eager to support this effort.”

The university already has raised $2.8 billion toward its goal.

Included in the capital campaign’s total is the largest private gift in U.Va.’s history — a $120 million donation made in January 2019 from husband-and-wife alumni Jaffray and Merrill Woodriff to establish the U.Va. School of Data Science. The university’s 12th school won approval from the State Council of Higher Education for Virginia in September and will build on the degree programs previously offered by U.Va.’s Data Science Institute.

Described as a “school without walls” that will conduct interdisciplinary research, it eventually will be housed in a 70,000-square-foot facility planned for the intersection of Emmet Street and Ivy Road.

A ‘bright opportunity’

Walentas hopes his gift “becomes the bright opportunity for other first-generation students to receive a quality education and life-changing experience.

“I know what it’s like to be held back by financial constraints, so I took advantage of every opportunity that came my way,” he says.

His comment echoes Robinson’s assessment of how a scholarship already has broadened her world.

“I don’t think people always realize what an education means to a first-generation student,” she says. “When I say my education means everything for me, it’s not just for me — it’s for my parents as well.”

When Robinson was growing up, her household wasn’t the strongest financially, she says. “Everything always came down to the dollar.”

The idea of going out of state seemed out of reach, and that wasn’t really on her radar anyway. “I never had a true dream school per se, especially as a first-gen [student]. It’s not like my mom went to so-and-so school,” Robinson explains. She expected she would go to college in Delaware and live at home to cut expenses.

But after she learned about U.Va. through a teacher who was a graduate, she was able to access scholarships and financial aid that cover the majority of her out-of-state tuition. She works part time at Starbucks and has taken out loans to cover her living expenses. Last year, she worked two jobs, including one with the student fundraising program Cavalier Connect.

The university has increased its efforts to enroll more first-generation students, who number more than 500 in this year’s entering class, a 19% rise from the previous year.

21st-century life prep

U.Va. also has bolstered programs to help first-generation students navigate life on the Grounds, and that has helped build a community “so you don’t feel like you’re alone,” Robinson says.

First-generation students “add a hustle and grind and an appreciation for education,” she says. But “you are surrounded by a lot of legacy children [who] knew U.Va. was in their blood, where, for me, I didn’t really know U.Va. existed.”

Robinson had the chance to engage with students from different backgrounds during her first year, when she opted into a new curriculum being piloted by the College of Arts & Sciences.

In October, the Arts & Sciences faculty voted to fully adopt the New College Curriculum for students to fulfill general education requirements.

The redesigned curriculum introduces first-year students to fundamental modes of inquiry through engagement courses with a format that Robinson says gave her “different points of view related to real-world topics.” The way the courses were structured resulted in “a lot more dialogue with the person next to me,” she says.

The curriculum also focuses on what the college terms “vital literacies,” stressing writing skills, proficiency in a second language and “quantitative and computational fluency essential to navigating an ever more data-driven world.”

Arts & Sciences Dean Ian Baucom says the revision represents the first major change in the school’s curriculum in more than 40 years.

“At a time when a liberal arts education is under heavy scrutiny, we are staking a claim on the power of what it can do for our students, especially as they enter an increasingly complex and interconnected world,” Baucom adds.

Through the engagement courses, he says, “students learn fundamental habits of mind to better prepare them for 21st-century lives — from wrestling with ethical questions, to fully appreciating the arts and aesthetics, to understanding empirical truths as scientists do, to engaging differences constructively in a world of people with different views, histories and backgrounds.”

At its September meeting, SCHEV also approved a master’s program in media, culture and technology that Baucom says reflects employer demand and student interest.

“Beyond the Facebooks and Googles of the world, there are agencies, consulting firms and other organizations looking for talent in media research and policy,” he says. “In a similar way, we think Amazon’s HQ2 will have an impact on the market for this in Northern Virginia.”

Living wage commitment

Despite all this progress, the fall semester saw the university gather some negative press after a Kaiser Health News analysis detailed how the U.Va. Health System’s aggressive pursuit of unpaid medical bills was forcing families into bankruptcy. The report led Ryan and Gov. Ralph Northam, both of whom said they were unaware of the practices, to promise reforms.

The university also stepped up to aid low-income employees as Ryan announced an agreement with major contractors to increase the minimum wage for most university contractors to at least $15 an hour. The agreement meant a raise for about 800 full-time contracted employees and followed the announcement in March of the “living wage” commitment for the university’s full-time, benefits-eligible workers in both the academic and medical divisions.

The increases were effective Jan. 1. About 1,400 university workers were covered by the March decision at an added annual cost of about $3.5 million to U.Va.

According to the university, the lowest salary its workers were making was $12.75 per hour, compared with the federal minimum wage of $7.25 per hour.

At her part-time job at the Starbucks in Newcomb Hall, Robinson says she works with people who will benefit from that decision.

“I think I value that job so much because I can converse with people from the Charlottesville community,” she says.

She’s had the opportunity to share some of what she’s learned as a first-generation student with a co-worker worried about how she will afford college for her daughter.

“A lot of those same struggles my parents were going through,” Robinson says.

o