A labor question

Virginia’s right-to-work law may become an election issue

Less than three years after voters rejected enshrining Virginia’s right-to-work law in the state constitution, the recent General Assembly session saw an effort to repeal the law altogether.

Del. Lee Carter, a first-term Democrat and professed socialist from Manassas, sponsored legislation to revoke Virginia’s right-to-work law, which has been in effect since 1947.

Such laws prohibit collective bargaining agreements requiring workers to join unions or pay union fees as a condition of their employment.

Like many other labor-related bills Carter sponsored, the repeal bill was left in committee, never receiving a vote in the Republican-controlled House of Delegates.

“When workers form a union, everyone in the workplace benefits from higher wages and better conditions,” Carter tweeted in December (he had more than 33,000 followers on Twitter in March). “But ever since 1947, Virginia has allowed some to freeload off of their co-workers’ hard-won union without paying dues. I’ve filed [this bill] to end this 70+-year injustice.”

Without a vote from the full house, it’s difficult to gauge just how much support there is among Virginia lawmakers to repeal right-to-work or take a more liberal stance on labor issues. In 2016, the push to let voters decide on adding a right-to-work amendment to the state constitution was passed by the General Assembly on party-line votes. Carter did not respond to multiple requests for comment.

Debate over the law isn’t over, however. Once accepted by both parties as an economic development selling point, Virginia’s right-to-work law may become an issue in the upcoming November legislative elections. That vote could tip total control of the legislature to the Democrats for the first time in decades. If the GOP keeps control, it may make another attempt to protect right-to-work in the constitution.

One of the candidates elected to the House in a 2017 Democratic wave, Carter has gained a national reputation for challenging Virginia’s business policies. In addition to his attempt to overturn the right-to-work law, he opposes giving big incentive packages to major companies considering locating or expanding in Virginia. Carter, for example, criticized a $70 million state grant given to Micron Technology for a $3 billion semiconductor plant expansion expected to create 1,100 jobs in his district.

“That money isn’t make or break for Micron,” Carter wrote in an op-ed published on the website for Jacobin, a socialist magazine. “Workers in Manassas won’t see any of the benefits.”

The Republican Party of Virginia supports the right-to-work law as an advantage in competing with other states.

“Repealing [right-to-work] would harm the Virginia economy and cost Virginia jobs,” John March, the state Republican Party’s spokesman, said in an email. “We supported our Republican legislators who fought the repeal bill. Right-to-work will likely be an issue in November along with several other issues that show the difference between Republicans and Democrats.”

But most Virginia Democrats appear reluctant to take a stand on the issue. Democratic Party of Virginia spokesman Jake Rubenstein would not say what the state party’s position is on right-to-work or whether it supports repealing the law. He directed Virginia Business to the Democratic caucuses in the state House of Delegates and Senate, neither of which responded to requests for comment. The Democratic leadership in the House and Senate and Gov. Ralph Northam also did not respond to requests for comment for this story.

In the past, right to work has has been supported by Democratic and Republican governors. A spokesperson for U.S. Sen. Tim Kaine, a Democrat who served as governor from 2006 to 2010, said in an email that he has supported Virginia’s current right-to-work law but opposed adding it to the state constitution. “He believes in strong unions just as he believes in good management,” the spokesperson said.

With only Carter so far making the repeal of right-to-work an issue, it’s unclear just how much of a role it will play in November when all 100 House and all 40 Senate seats will be up for election.

“The right-to-work law is one of the fundamental aspects of a strong and vibrant business climate in the commonwealth,” Gilbert says. “We are consistently ranked as one of the top places to do business. Right-to-work is essential to those rankings and to our strong competitive position.”

Gilbert says Republicans considered bringing the right-to-work repeal bill up for a vote during the General Assembly session, with full confidence the legislation wouldn’t pass. Such was the fate of a proposal in Virginia’s Senate to raise the state’s minimum wage from the federal minimum of $7.25 an hour to $15 by 2021. Senate Republicans defeated the bill on a party-line vote, 21-19, as a way of illustrating what could happen under a Democratic majority, according to the Richmond Times-Dispatch.

“I don’t think it’s going away,” Gilbert says of labor issues like right-to-work. “Given the opportunity, we would certainly revisit putting [right-to-work] in the constitution.”

Deirdre Condit, a feminist political theorist at Virginia Commonwealth University, says protecting right-to-work would play well with the Republican base, but she believes the issue is unlikely to help the party attract more moderate voters. Condit says a progressive agenda hasn’t taken root in the state Democratic Party. She nonetheless thinks the fact that

Carter’s bill was introduced shows that some Democrats are confident enough to advance more liberal policies.

An early adopter

Virginia was among America’s earliest adopters of a right-to-work law. In addition to prohibiting companies from making their workers union members, the law forbids employers from forcing employees to pay union dues. It also forbids companies from preventing employees from joining unions.

The National Labor Relations Act (also known as the Wagner Act) was enacted in 1935, guaranteeing workers the right to organize and bargain collectively. At the time, companies were refusing to negotiate with employees, a stance that resulted in strikes that hampered the economy.

The law also permitted contracts between employers and labor organizations that required every employee covered by a collective bargaining contract to pay union dues. In 1947, the federal statute was substantially amended by the Taft-Hartley Act, which allowed states to establish what came to be known as right-to-work laws forbidding such requirements.

“Whereas the original Wagner Act focused on asserting the rights of workers and organized labor, the Taft-Hartley Act addresses employers, employees and labor unions as equal parties in the negotiation process,” a 2014 Congressional Research Service report reads. “[Taft-Hartley] also prohibited secondary strikes and outlawed so-called ‘closed shops’ that required an employee to be a union member prior to being hired.”

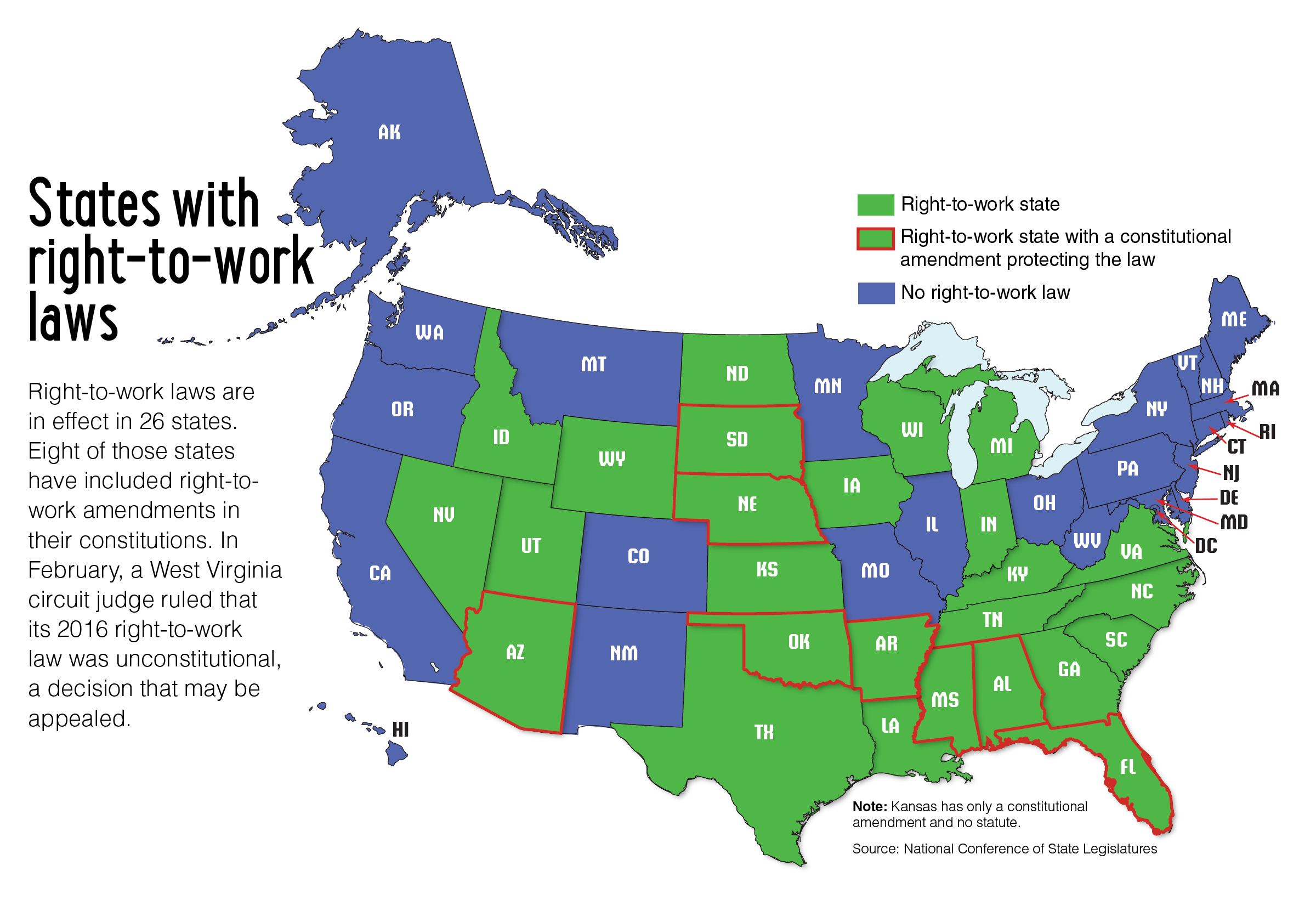

Eight states have both a right-to-work statute and a constitutional amendment. Virginia attempted to join their ranks in 2016. The commonwealth’s voters, however, rejected a proposal to add a right-to-work amendment to the state constitution, with 53.62 percent of the 3.76 million votes cast being against the move.

Right-to-work continues to be debated around the country. In February, a circuit judge in West Virginia struck down the state’s 2016 right-to-work law, calling it arbitrary to “require unions and union officials to work, to supply their valuable expertise and to provide expensive services for nothing.” Last year, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled 5-4 that nonunion workers cannot be forced to pay fees to public-sector unions.

The rise of right-to-work laws has coincided with — some would say helped fuel — the national decline in union membership. After Kentucky adopted a right-to-work law in 2017, the state saw its percentage of employed workers in unions drop at a faster rate than the ongoing national decline. In 2016, 11.1 percent of Kentucky’s employed workers were members of a union. By last year, that number had dropped to 8.9 percent. Nationally, union membership declined from 10.7 percent of the workforce in 2017 to 10.5 percent in 2018.

When Indiana adopted a right to work law in 2012, the percentage of employed workers in unions was at 9.1 percent, down from 21 percent in 1989. After ticking up to 10.7 percent in 2014, union membership had dropped to 8.9 percent — its lowest level in years — by 2017.

Pros and cons

Proponents see right-to-work as an economic and a free speech issue. They argue that businesses prefer to invest in right-to-work states, and they object to the idea that workers should be forced to pay dues to an organization they might not support.

“It would be detrimental for the General Assembly to repeal current right-to-work protections, which may cause existing employers to move facilities to surrounding states with more favorable business climates,” Barry E. DuVal, president and CEO of the Virginia Chamber of Commerce, said in an email.

Opponents of right-to-work say that it’s unfair for nonunion employees to benefit from union contracts without paying for the service. (In 1961, Martin Luther King Jr. said right-to-work “is a law to rob us of our civil rights and job rights.”)

“Virginia must repeal its right-to-work law,” Doris Crouse-Mays, the president of the Virginia AFL-CIO, said in a statement. “We believe repealing Virginia’s right-to-work law would do two things at once: Give more workers a voice on the job and raise wages.”

Opponents suggest other factors are more important in driving business decisions, such as a skilled workforce and good infrastructure.

While opinions are strong on both sides of the issue, academic consensus on right-to-work’s impact on economic development has been illusive. The 2014 report on right-to-work by Benjamin Collins published by the Congressional Research Service called research on the economic benefits of being a right-to-work state “frequently conflicting.”

“The literature related to the laws’ effects on higher-order outcomes such as employment and wages is inconclusive,” the report reads. “Studies have yielded a variety of conclusions, largely dependent on how researchers conduct their analyses.”

The report mentions a “frequently cited” 1998 study by Thomas J. Holmes called, “The Effect of State Policies on the Location of Manufacturing: Evidence from State Borders.” Holmes analyzed manufacturing employment numbers from 1947 (when Taft-Hartley was passed) to 1992 in counties along the borderlines of states that had right-to-work laws and other states that didn’t. His idea was to compare manufacturing employment in areas that share similar features, such as geography and infrastructure, but had different policies on right-to-work. The goal was to isolate as much as possible the impact of right-to-work laws.

Holmes found that on average there is an abrupt increase in manufacturing activity when one crosses the line from a non-right-to-work state into a right- to-work state.

Nonetheless, he cautioned against putting too much stock in the impact of a right-to-work law itself. Labor groups echo this sentiment today.

“We don’t feel Virginia’s right-to-work status is a primary issue when companies are looking to invest in Virginia,” says Crouse-Mays of the Virginia AFL-CIO. “When businesses come to any state — Virginia included — they are looking for a strong economy, well-trained workforce, quality public education system, and a transportation infrastructure that will assist in running their company smoothly.”

Others, however, insist that right-to-work laws drive business decisions.

“Right-to-work is a critical site selection factor,” says John Boyd of the Boyd Co., a national site selection firm based in New Jersey. “Virginia should continue in the model that’s brought it so much success.”

Virginia has long had a reputation as a pro-business state. CNBC ranked Virginia No. 4 on its 2018 list of America’s Top States for Business. The state got an A+ for its workforce, which accounts for the highest number of points in CNBC’s ranking methodology and includes consideration of union membership and right-to-work laws.

“While organized labor contends that a union workforce is a quality workforce, that argument, more often than not, does not resonate with business,” CNBC explains in its methodology.

Impact on politics

Fail though it did, Carter’s effort to repeal right-to-work in Virginia made waves in the local and national press. For or against, editorial reactions to the bill mostly reflected where the authors stood.

An InsideNova.com editorial bemoaned Carter’s focus on labor issues at the expense of the interests of his constituents.

“Nothing could be a better example of this than his ill-fated attempt to repeal Virginia’s right-to-work law, which has been in place for more than 70 years and is an oft-cited reason for the state’s economic success,” the editorial said.

At the other end of the spectrum, the headline of a story by The Nation magazine crowed, “Lee Carter’s campaign for labor rights in Virginia is important for all working Americans.”

Labor groups like the Mid-Atlantic Region of the Laborers’ International Union of North America (LIUNA) see the repeal bill as a sign that views on right-to-work are shifting in Virginia.

Brian Petruska, general counsel for Mid-Atlantic LIUNA, says there is hope that support for repealing the law could eventually become a hallmark for state Democrats. That’s already the case at the national level. The 2016 Democratic Party platform reads in part, “Democrats believe so-called ‘right-to-work’ laws are wrong for workers,” and calls for vigorous opposition of the policy.

“The filing of Lee Carter’s bill was sort of a signal about how Virginia is changing as a state,” Petruska says. “We want support for labor to be understood as a litmus test.”

i