A healthier state?

Virginia is preparing for Medicaid expansion on Jan. 1

A healthier state?

Virginia is preparing for Medicaid expansion on Jan. 1

A former construction worker was in such despair that he got down on his knees in George Washington University Hospital’s emergency room and begged Dr. Jennifer Lee for help.

The man had been to the ER in Washington, D.C., many times before, desperate for a hip replacement. He told Lee that he didn’t want to go on disability. He wanted to go back to work.

But she had to tell him that his debilitating condition was not life-threatening, and without health insurance she couldn’t help.

“I thought about him so many times because it was really distressing to me as a doctor that I could not help him to get what he needed,” she says of the incident, which occurred before the District of Columbia expanded its Medicaid program.

Now director of the state Department of Medical Assistance Services (DMAS), Lee is overseeing the expansion of Medicaid health coverage on Jan. 1 to as many as 400,000 Virginians — including low-income adults of working age without children.

Lee is optimistic that the new benefits will improve their health and the state’s economy, too.

Budget compromise

But a budget compromise in May ended the impasse, allowing Virginia to accept more than $2 billion in federal funds to pay for about 90 percent of the expansion costs. The state’s share of the cost will be financed by new assessment fees — essentially a tax — on hospital revenues.

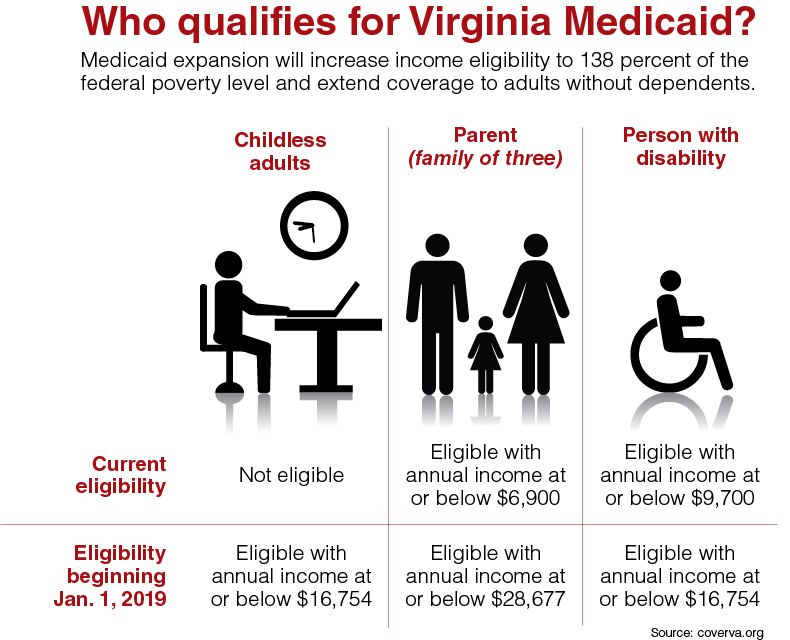

Until now, Virginia has had one of the most restrictive Medicaid programs in the nation, ranking 46th among states in per-capita spending, according to DMAS. Expansion under ACA will increase the income eligibility level to 138 percent of the federal poverty level and extend coverage to adults without dependents.

Before expansion, a childless adult without a disability was not eligible for Medicaid. Beginning next year, an adult with an annual income at or below $16,754 can sign up for the program.

A family of three will be eligible with an income at or below $28,677, quadrupling the previous threshold of $6,900. For a disabled person, the eligibility level goes from $9,700 to $16,754.

Virginia joins 32 other states and the District of Columbia in agreeing to expand Medicaid coverage. Originally a key component of ACA, Medicaid expansion became optional for each state in a 2012 U.S. Supreme Court ruling upholding the health-care law’s legality.

Work/training rule

Lee says her office is “working very intensely” on two tracks to gain federal approval of the state’s Medicaid plan. In addition to amendments to the existing plan, the state is seeking approval of a waiver that would tie recipients’ benefits to work, study or civic engagement requirements.

The addition of the Training, Education and Employment Opportunity Program for Medicaid beneficiaries was part of the budget compromise. The requirement would apply to some current Medicaid recipients as well as new ones. In November, the commonwealth will ask for federal approval for a waiver, known as the 1115 Demonstration Waiver, that would allow the requirement to take effect.

While Medicaid expansion is on track for the Jan. 1 launch, Lee says the timetable for implementing the waiver provisions is less certain. In a potential complication, a federal judge in June struck down a similar work/training requirement in Kentucky.

Lee points to the man with chronic hip pain she met in the ER to explain her view on the requirement.

“People want to be well. People want to work. They want to pursue more opportunity,” she says. “But they need some help to deal with an injury or an illness to get them back on their feet.”

Net savings?

With Medicaid expansion, the commonwealth will receive $2.4 billion in federal funds for fiscal years 2019 and 2020 to pay for 90 percent of the costs of caring for newly eligible recipients. That federal infusion, Lee says, will result in net savings of $355 million to the state’s General Fund for those years.

“Medicaid expansion actually results in net savings to the commonwealth,” she says. “I know that sounds counterintuitive.”

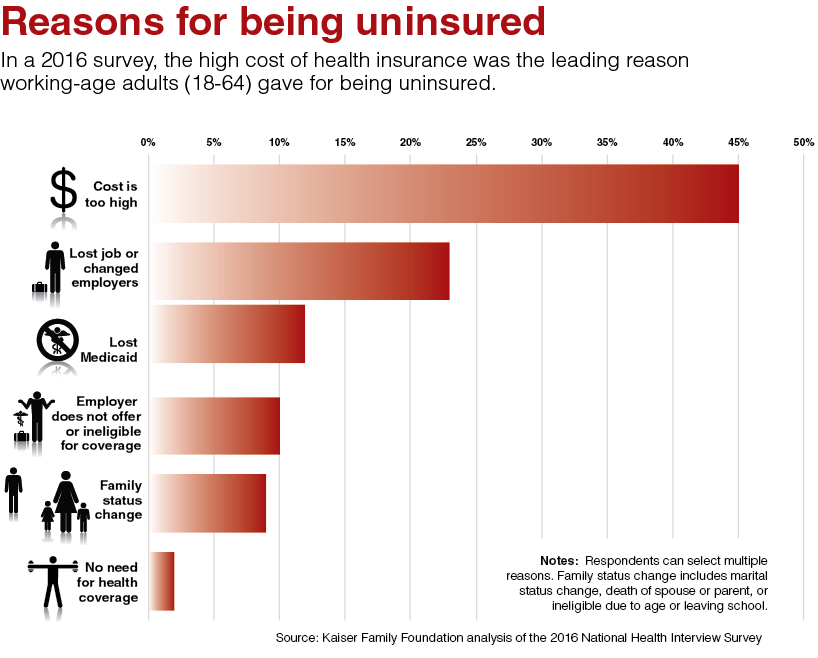

Expansion is expected to close the “Medicaid gap” that leaves many low-income Virginians without insurance options. These are adults who are ineligible for the existing Medicaid program but did not earn the minimum income required for receiving insurance subsidies under ACA.

With the higher income threshold under expanded Medicaid, some people who received subsidized insurance on the health exchange may now qualify for Medicaid.

Lee says DMAS is trying to determine how many people fall in each of those groups. Doug Gray, executive director of the Virginia Association of Health Plans (VAHP), says he has seen estimates that as many as 90,000 people now insured through the ACA exchange may be eligible to move to Medicaid plans.

Also uncertain is the health status of new Medicaid enrollees who will make up the risk pools for six managed-care plans offered by insurance companies under Medicaid. The plan providers can earn a profit up to 3 percent above their underwriting gain, Gray says, with any percentage above that being shared with the state.

For example, if profits exceed 3 percent — an event Gray says is unlikely — half of the amount up to 10 percent would be returned to the state.

Premiums are to be based on a sliding scale not to exceed 2 percent of monthly income for those between 100 percent and 138 percent of the federal poverty level.

“Part of the challenge is to develop a rate to pay for the new enrollees,” Gray says. “Some are going to be much sicker than others.”

But the state will benefit, he says, as a large number of people with chronic conditions — diabetes, asthma, heart disease — will get treatment early on “instead of having to go to the ER for help after it’s too late.”

Health exchange effects

Gray says it is too soon to gauge the impact of Medicaid expansion on premiums paid on the health exchange. Some very sick patients may leave the exchange for Medicaid, but healthier people now on the exchange also may move to Medicaid. Either move could affect the exchange risk pool.

“It will be a mix. The question is: When the mix is all said and done, is the net effect a reduction for premiums?” he says.

In July, insurance companies told the State Corporation Commission that rates for individuals covered under ACA’s Virginia exchange are expected to increase by an average of about 13 percent next year.

Lee says a 2016 study found that states with expanded Medicaid plans saw an average drop of 7 percent in premiums for health insurance policies bought through marketplace exchanges.

But that study by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Service predates the election of President Donald Trump and subsequent cuts to federal cost-sharing reduction payments that subsidize ACA policies.

Assessment fees

The General Assembly approved two provider assessment fees as part of Medicaid expansion.

The assessments on hospital revenue will be imposed on 69 private, acute-care hospitals, according to Julian Walker, vice president of communications for the Virginia Hospital & Healthcare Association. Exempt are children’s and specialty hospitals, such as psychiatric and rehabilitative facilities, and the University of Virginia and Virginia Commonwealth University medical centers.

One assessment fee, which will pay for Virginia’s 10 percent share of Medicaid expansion, is expected to yield $281 million during the two-year budget cycle and up to $300 million annually in subsequent years, Walker says.

The second assessment will be used to increase the reimbursement rate for treating Medicaid patients. The reimbursement rate now is 71 percent, or 71 cents for each dollar of care, despite state law that sets the acceptable level at 78 percent, Walker says.

The rate will increase to 88 percent with the second assessment fee, which is expected to bring in about $250 million. However, Walker says the exact numbers remain uncertain because the implementation process is ongoing. The state is expected to begin collecting the assessment payments in October.

Although hospitals are paying the state’s cost for Medicaid expansion, Walker says, they will receive only about 36 percent of revenue that will be generated.

Other health-care providers such as pharmacies, home health-care businesses, medical equipment companies and labs are among beneficiaries that won’t be subject to the tax, he notes.

Hospitals will benefit as a result of the increased Medicaid reimbursement rates as well as from a reduction in the uncompensated care of uninsured patients, Walker says. But, it’s still not clear how many people will actually enroll in Medicaid. “The challenge of uncompensated care will not vanish,” he says.

The association historically has opposed provider assessments but agreed to the bipartisan proposal to facilitate Medicaid expansion and to improve reimbursement rates, Walker says.

‘In-reach program’

Getting Medicaid expansion up and running requires a multi-partner push, says VAHP’s Gray. “People aren’t going to be just magically enrolled” on Jan. 1, he says.

At community health centers that treat people across the state regardless of their ability to pay, officials are contacting patients who might be Medicaid eligible to walk them through the enrollment process.

“We have what we call an in-reach program,” says R. Neal Graham, CEO of the Virginia Community Healthcare Association.

The centers see about 106,000 uninsured patients, the majority earning up to 200 percent of the federal poverty level, he says. As many as 70,000 might qualify for Medicaid under the 138 percent income level cutoff, with about 75 percent of those enrolling.

“Most of our people — the vast majority who are uninsured — are employed or working part time. They just don’t earn enough,” he says.

Many earning under 200 percent of the poverty level can’t afford insurance, he explains. “So, we’re worried about that group that is at 138 percent to 200 percent that won’t qualify for Medicaid but still won’t be able to afford insurance.”

Many others in the state won’t be eligible for Medicaid because of their immigration status. Undocumented immigrants do not qualify, and immigrants with legal status are not immediately eligible.

“We’re still going to need our safety net system, our free clinics to fill in the gaps,” Lee says. “But those gaps are going to be a lot smaller.”

s