A dose of inspiration

Pandemic disrupts med schools, boosts applications

A dose of inspiration

Pandemic disrupts med schools, boosts applications

Admissions officers call it “the Fauci effect.”

Inspired by Dr. Anthony Fauci, chief medical adviser to President Joe Biden and the highly visible point person for the nation’s COVID-19 pandemic response, prospective students have been flooding medical schools with applications.

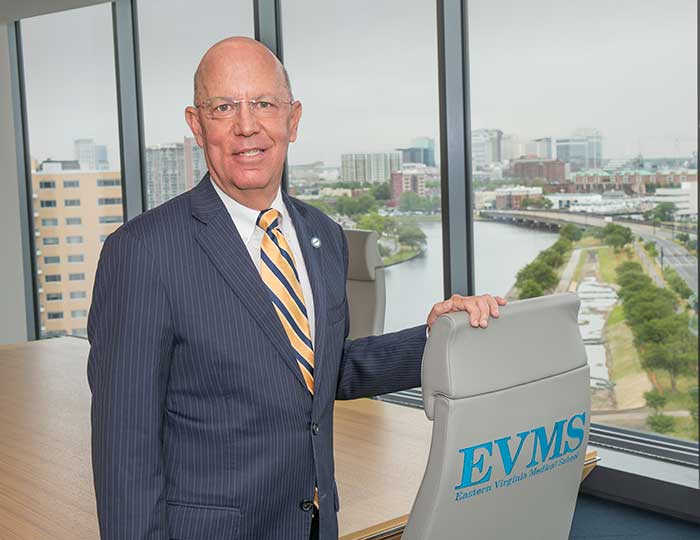

But Dr. Richard V. Homan, president and provost of Eastern Virginia Medical School and dean of its School of Medicine, has another theory about why applications have increased. He says it speaks to a sense of duty brought on by a national crisis: “It’s like 9/11, when a lot of individuals elected to go into the military. People wanted to contribute.”

The American Medical College Application Service reported a nearly 17% increase in applications last fall. During the past decade, the year-over-year increase in applications had been below 3%.

Medical schools in Virginia have experienced the same trend since the start of the pandemic.

At Eastern Virginia Medical School applications were up almost 30% — from 6,800 to more than 8,800 for 151 slots, Homan says.

The school offers more than 20 health programs, and Homan sees a heightened interest in health professions such as physician assistants and public health workers. (The national Association of Schools and Programs of Public Health reported a 20% nationwide increase in applications to master’s in public health programs last fall.)

The Virginia Tech Carilion School of Medicine in Roanoke received 6,374 applications for the class that starts this summer. That’s a 45% increase over the 4,400 annual applications the school has received on average since 2016.

“You hear the talk about the ‘Fauci effect,’” says Dr. Aubrey L. Knight, the school’s senior dean for student affairs, but there’s another important factor as well — the pandemic also moved the application process completely online for many medical schools. In the past, the application process generally started virtually and was followed up with on-campus interviews.

Dr. John J. Densmore, associate dean for admissions and student affairs at the University of Virginia School of Medicine in Charlottesville, notes that “medical schools have always interviewed people in person. The switch to virtual made it much less expensive for applicants.” U.Va.’s School of Medicine saw a 35% increase in applications for fall 2020, Densmore says.

The Virginia Commonwealth University School of Medicine in Richmond reports that applications jumped from 7,309 applicants for the fall 2020 class to 8,185 applicants for the fall 2021 class, according to Dr. Michelle Y. Whitehurst-Cook, senior associate dean for admissions.

Knight says that there were concerns that, with the virtual application process, potential Virginia Tech students might not be able to tell if they were a good fit with the school, and the school wouldn’t be able to tell whether a student was a good match. However, the process went better than he expected.

The school “was able to do a good job not only [with] virtual interviews but [with] virtual meetings,” he says, and was able to offer students detailed information about the program and the overall educational experience. “There was less of an impact than I was fearing. We don’t know whether we will be doing virtual interviews this year, but if we do it again, I won’t be as afraid.”

Virtual learning

The pandemic not only changed the application process for medical school, it also changed the way medical students are being taught and tested. The need for social distancing shifted many medical school classes from in-person to online.

“It changed the teaching process dramatically,” Densmore says. At U.Va., students traditionally spend their first 18 months largely in the classroom, followed by more than two years of hospital and clinic work.

In spring 2020, preclinical classes went entirely virtual, with course directors hurrying to change to an online format. “In the fall, there were some in-person options,” he says. “We have continued to expand that this spring, particularly as our students are vaccinated.”

On-site visits to learn clinical skills were shut down for about 12 weeks beginning in spring 2020 and students switched to virtual electives. Medical school students began returning to hospitals and clinics in summer 2020 but were limited initially by a shortage of personal protective equipment, Densmore says.

Knight has found the shift in teaching methods to be “a very mixed bag,” he says. “There are things we’ve learned from the [new] application and education process that may never go away.”

He’s heard good things from students about the revised approach to basic science education. “We’ve learned a lot about virtual learning, as well as the value of providing alternative options instead of stand-and-deliver lectures. I think that … will outlive the pandemic.”

And he believes “students were very appreciative of the ways in which we very quickly made sure we attended to their safety and to the safety of patients. Carilion was sensitive to everyone’s needs.”

Still, “when we had to pull students from hospitals and clinics, it was a big challenge to keep them on track,” Knight says. “I know it limited the patient contact they had. That’s not a good thing. We want to send our students out from here as well-versed in clinical medicine as possible. The limits have taken a toll.”

Med schools get a checkup

Dr. Christopher Woleben, the VCU School of Medicine’s interim senior associate dean for medical education and student affairs, thinks some of the pandemic-driven changes have been for the better, though, particularly in preclinical education.

“I think we’ve learned to do remote learning technology better,” such as creating virtual breakout discussion groups, says Woleben, who is also an associate professor in the school’s Department of Emergency Medicine.

Once the pandemic hit, the school quickly had Zoom video conferences up and running for preclinical students. “We continue to have some in-person experiences in small groups. Of course, we’ve had to change the rooms and the timing to make sure we’re meeting requirements for social distancing,” Woleben says. “We’re hoping to transition back to more traditional in-person classes in the fall. I think we will continue to offer opportunities for students to participate virtually. It will probably be a hybrid experience. “

From March through June 2020, Woleben continues, “we were not sure what was going on, how to keep clinical-phase students safe,” so students were temporarily moved from in-person clinical training to online elective classes.

Third-year students took an eight-week nonclinical course until it was deemed safe to return to the health system in July 2020.

Fourth-year medical students returned to clinical work in June 2020. With a shortened timeframe to prepare to apply for residencies, “individual schedules were designed by hand to make sure they got the experiences they needed. It was a lot of all-hands-on-deck,” he says.

Woleben is proud of his medical students’ response to the pandemic crisis. Many stepped up as volunteers to conduct contact tracing for the Medical Reserve Corps, a national network of community-based units that provide volunteer assistance for public health initiatives and emergencies. “Their question was: ‘How can I help?’”

Waleed Ahmad, who recently finished his first year at the VCU School of Medicine, applied to medical school before the pandemic hit, but by the time he started in August 2020, classes were mostly online.

The virtual experience was “pretty well done,” offering opportunities for small group meetings, says Ahmad, a native of Loudoun County and a graduate of James Madison University. He is president of the school’s class of 2024.

As a first-year student, Ahmad didn’t examine actual patients, but he did take the required Practice of Clinical Medicine class, during which students perform exams on actors who portray patients. This year, however, the class broke into small groups, employing social distancing and wearing surgical masks and face shields.

“The toughest thing” about studying medicine online, Ahmad says, has been the lack of social contact with other students. “You work together. You study for exams and then have a sense of release together. The goal is to build a sense of community and cohesiveness. Our class missed that. I hope we have that next year.”

The Match game

The pandemic also disrupted a major medical school testing tradition. In March 2020, the Step 2 Clinical Skills medical licensing exam test was put on hold. The daylong in-person test was designed to assess potential physicians’ communication and physical exam skills. This January, the Federation of State Medical Boards and the National Board of Medical Examiners (NBME) — the exam’s sponsors — announced that they no longer had plans to revive it.

“The Match,” on the other hand, continues. On the third Friday of March each year, fourth-year medical students from around the nation take part in the nonprofit National Residency Match Program (NRMP). The Match determines where they will spend the next three to seven years of their residency training. The 2021 Main Residency Match saw the largest number of placements offered since the program began in 1952, with 35,194 first-year positions offered, according to the NRMP.

This year’s match was very similar to prior years, according to Woleben. He and other medical school officials say they didn’t see any last-minute changes in medical specialties on the part of this year’s fourth-year students, who are already locked into career paths.

But, Woleben says, “it will be interesting to see what happens with the third-year class. Will there be more interest in critical care, in infectious disease, in population health?”

The pandemic has raised awareness of the disparities that exist in health care, he believes, as well as making changes in the way classes are taught.

“I think that the pandemic will affect how everyone practices medicine. It will have a lasting effect.

Medical

schools in

Virginia

Virginia Commonwealth University School of Medicine

Main Campus: Richmond

Website: medschool.vcu.edu

Annual in-state tuition and fees1: $37,143

Dean: Dr. Peter Buckley

No. of students: 765

No. of faculty: 3,461

Eastern Virginia Medical School

Main Campus: Norfolk

Website: evms.edu

Annual in-state tuition and fees1: $32,456

President/Dean: Dr. Richard V. Homan

No. of students: 1,384

No. of faculty: 545

Edward Via College of Osteopathic Medicine

Main Campus: Blacksburg

Website: vcom.edu

Annual tuition and fees1: $46,900

President: Dr. Dixie Tooke-Rawlins

No. of students: 2,122

No. of faculty: 133

Liberty University College of Osteopathic Medicine

Main Campus: Lynchburg

Website: liberty.edu/lucom

Annual tuition and fees1: $49,910

Dean: Dr. Joseph R. Johnson2

No. of students: 621

No. of faculty: 53

University of Virginia School of Medicine

Main Campus: Charlottesville

Website: med.virginia.edu

Annual in-state tuition and fees1: $48,690

Dean: Dr. David S. Wilkes

No. of students: 630

No. of faculty: 1,254

Virginia Tech Carilion School of Medicine

Main Campus: Roanoke

Website: medicine.vtc.edu

Annual in-state tuition and fees1: $56,092

Dean: Dr. Lee A. Learman

No. of students: 175

No. of faculty: 829

1 Estimates based on tuition plus semester, annual and one-time fees

2 Interim dean

Sources: Universities, Virginia Business research