Interest rate

Med students aren’t flocking to in-demand specialties. Why?

Sabrina Moreno //December 31, 2023//

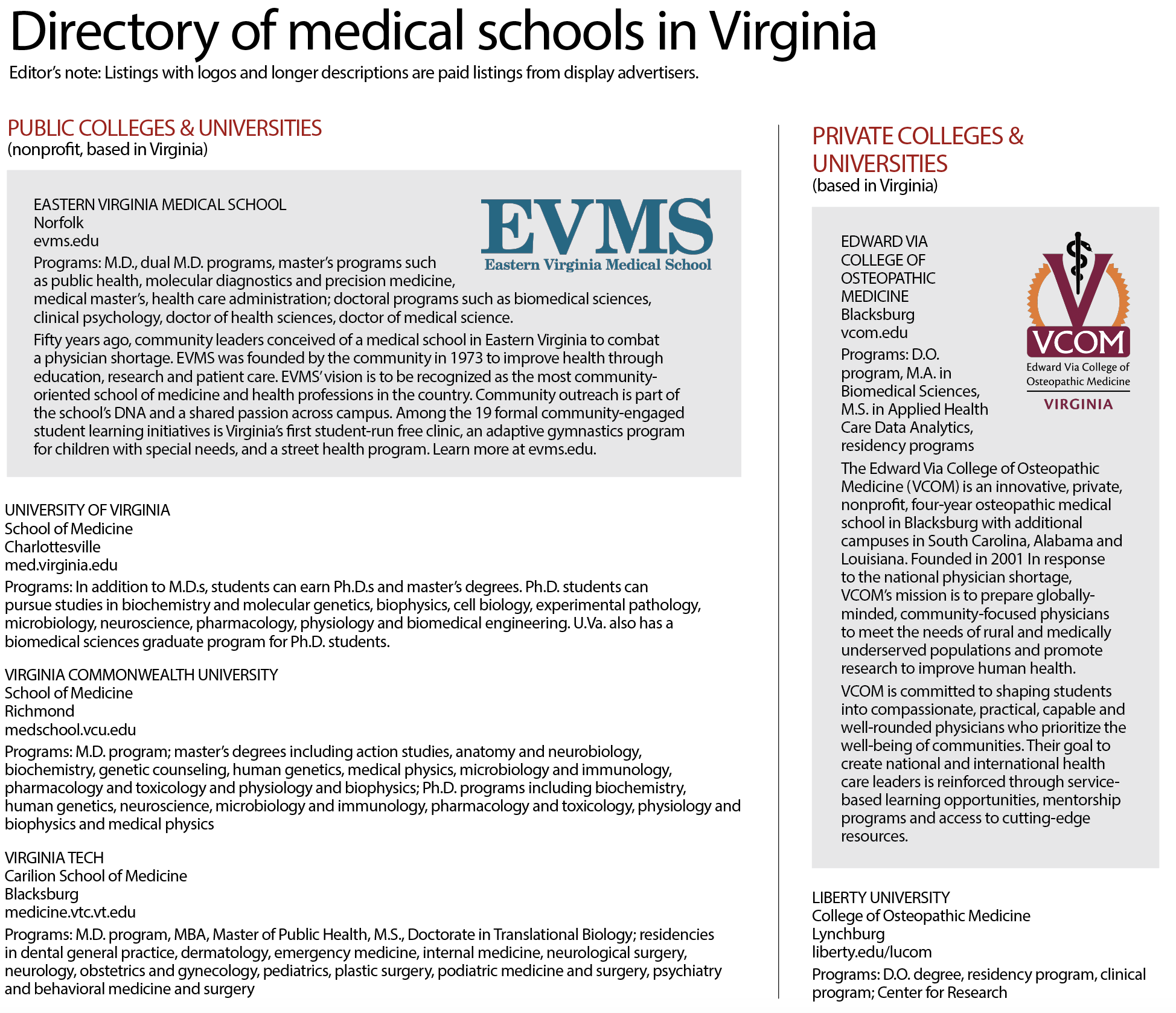

A professor of family medicine and senior dean of student affairs at Virginia Tech Carilion Medicine, Dr. Aubrey Knight is also a geriatrician, a medical specialty facing a shortage of more than 22,000 doctors by 2030. Photo by Don Petersen

A professor of family medicine and senior dean of student affairs at Virginia Tech Carilion Medicine, Dr. Aubrey Knight is also a geriatrician, a medical specialty facing a shortage of more than 22,000 doctors by 2030. Photo by Don Petersen

Interest rate

Med students aren’t flocking to in-demand specialties. Why?

Sabrina Moreno //December 31, 2023//

Dr. Aubrey Knight has spent his career listening to stories about the past. He’s talked to people who were miners during World War I. He’s spoken to Prohibition-era bootleggers. He’s heard endless stories of relationships severed then reconciled decades later.

That comes with the territory for geriatricians like Knight who specialize in treating older adults. A professor of family medicine and senior dean of student affairs at Virginia Tech Carilion School of Medicine, he says the joy and sense of accomplishment he associates with the specialty is what drew him to choose it more than 30 years ago.

With more than 56 million Americans now 65 and older, geriatrics is one of the specialties most in need of doctors due to a large population of aging baby boomers. But most of today’s medical students don’t feel the same pull for the specialty that Knight did.

The American Geriatrics Society estimates that the U.S. will need 30,000 geriatricians by 2030 to meet health care needs, but there are currently fewer than 7,300 geriatricians practicing in the nation.

The urgent need for geriatricians and other specialists shows how competing medical needs in an industry barraged with burnout and staffing shortages — especially among the primary care and behavioral health workforces — is leaving gaps in patient care.

It’s also creating a challenge for Virginia medical school leaders who want to encourage students to flock toward in-need specialties while making sure they also choose a career that will fulfill them.

Those two goals don’t always line up.

Family medicine, for example, is facing one of the most aggressive physician shortages in the U.S., but it’s not one of the most popular medical specialties — unlike dermatology, orthopedic surgery and anesthesiology, which are also among the most competitive residency programs to get into.

“What we don’t want is for a student to make the wrong decision, for a student to get into a specialty and to realize two or three years in, ‘This is not what I thought it was going to be,’” Knight says.

But no matter what specialty they choose, Dr. Lee A. Learman, VTCSOM’s dean since 2019, notes that graduating med school students are helping the health care industry battle an overall physician workforce shortage.

By 2034, the U.S. will be facing a shortfall of up to 124,000 physicians, according to projections from the Association of American Medical Colleges. Even surgical specialties, which are among the most popular and most competitive medical fields, are also facing severe shortages in rural areas and in the South. Nationwide, the AAMC projects surgical specialties could be short by up to 30,200 physicians

by 2034.

In a national address about the growing crisis in October 2023, American Medical Association President Dr. Jesse Ehrenfeld said, “While our current physician shortage is already limiting access to care for millions of people, it’s about to get much worse.”

Years in the making

Deciding on a medical specialty is a process years in the making, and it’s part of an additional three to seven years of residency that follows medical school before doctors formally join the workforce.

Medical students usually choose specialties after their third year of medical school, where as part of the core curriculum, they “rotate” or train in multiple specialties like internal medicine, general surgery, psychiatry or emergency medicine as part of an actual medical team.

Students then take what’s known as the Step 2 CK exam, a one-day test of clinical knowledge, such as treatments for given diagnoses. The exam determines a students’ competitiveness in applying to residency programs that train newly graduated physicians in specific medical specialties.

The more competitive the specialty, the higher a student needs to score on the exam to remain an attractive candidate, says Caila Bachmann, who is entering her fourth year as a medical student at the University of Virginia and plans to specialize in general surgery due to her love of hands-on work.

The fourth year of med school consists of electives that cater to a student’s expected specialty choice and can provide them a boost in their residency application process, which starts around September and is when they officially declare their desired medical specialty. Applicants are then matched with residency programs each March by the National Resident Matching Program. The number of applications submitted per person depends on the medical specialty.

Because the process is getting more competitive, med students are individually submitting more residency applications in order to raise their odds at landing a desired residency slot, Bachmann says. Med students are also putting in more applications because most residency interviews are now conducted virtually, eliminating travel time and expenses that applicants used to incur before the pandemic.

Mannet Dhaliwal, a fourth-year U.Va. medical student who aims to specialize in psychiatry, says she’s applied to more than 50 residency programs. A friend who wants to specialize in dermatology has applied to roughly 150 residency programs due to dermatology programs being smaller and among the most competitive, Dhaliwal says. The easiest programs to get into are often the ones most in need of doctors and require fewer applications, she says.

“We need a lot more pediatricians, so that’s why it’s ‘easier’ to get that residency,” Dhaliwal explains.

Decisions, decisions

The average Eastern Virginia Medical School graduate has $250,650 of school debt, according to a 2023 AAMC report, while graduates of Virginia Tech Carilion School of Medicine and the U.Va. School of Medicine incur $204,515 and $161,322 in average school debt respectively.

“I make a lot of jokes about [the debt] because I find it’s on my mind a lot,” Bachmann says. “And it’s easier to laugh than cry.”

But interest, desired lifestyle, level of patient interaction and work-life balance play heavier roles in the specialty decision-making process than salary, according to Bachmann and others.

Though Dr. Ronald Flenner, vice dean for academic affairs at Eastern Virginia Medical School, has met students whom he thinks would make “fantastic” primary care physicians, they’ve been turned away from it as a career option due to their school debt loads, he says.

Work-life balance, however, was the top consideration for 85% of new physicians choosing a job in 2022, compared with 63% in 2018, according to surveys from health staffing consultancy CHG Healthcare.

It’s a reason why dermatology, a profession limited mostly to daytime work hours, has remained consistently popular and why anesthesiology is growing as another desirable specialty nationally and among Virginia’s med school students.

Nationally, more specialized fields like thoracic surgery, neurosurgery, plastic surgery and orthopedic surgery are much more competitive and are more likely to see high percentages of people not make it into those residency programs due to limited slots. These specialties are also among the highest paid.

A neurosurgeon can expect an average annual salary of $788,313, while a family medicine doctor makes an average of $273,040, according to a 2023 physician compensation report from medical platform Doximity.

Psychiatry is a specialty that’s slowly becoming competitive, too, which Virginia’s medical school leaders attribute partly to a growing behavioral health crisis across the U.S.

More than 2,100 psychiatry positions were offered in the 2023 residency match nationwide, the highest ever recorded, and the specialty had 99% of its residency program slots filled, says Donna Lamb, president and CEO of the National Resident Matching Program.

Lamb and Virginia’s medical school leaders say Virginia’s medical students mirror national trends.

Bearing witness to industry stressors is also influencing med students’ choices on whether to pursue a particular specialty, says Dr. Meg Keeley, a pediatrician and senior associate dean for education at U.Va.’s School of Medicine.

“I would say the biggest shift that we have all experienced — not just in my medical school but across the country — is a fairly dramatic drop-off of students choosing to go into emergency medicine,” Keeley adds, which is in part due to stories about how emergency rooms were overwhelmed as they fought on the pandemic’s grueling frontlines.

Prior to COVID, emergency medicine was one of the most popular and competitive specialties for students to get into. But in 2023, the emergency medicine specialty had just 82% of available residency slots filled, down from 92.5% in 2022, Lamb says.

Third-year clinical rotations offer another glimpse into the industry, which leads some physicians to pull away from less competitive specialties with high industry needs like internal medicine when they see how difficult those specialties can be day-to-day, says Dhaliwal.

“The residency is very brutal. You are just basically working like 14-hour days for four years, six days a week,” Dhaliwal continues. “I think a lot of people just don’t want that life for themselves.”

For Mathew Ciurash, a third-year medical student at Virginia Commonwealth University’s School of Medicine, shadowing a resident anesthesiologist his first year had the opposite effect. Seeing how happy and fulfilled anesthesiologists were in their jobs is what cemented his decision to pursue anesthesiology as a specialty.

The pressure to be certain about the specialty one chooses can be tough, Ciurash explains, “because there’s … not really a looking back. Once I start a new residency, I’m … locked into a field that I better enjoy because it’s the rest of my career.”

Doctors in demand

The paradox facing medical schools is that the medical specialties experiencing the greatest shortages of doctors aren’t always the specialties medical students tend to pursue — and the issues deterring students from going into those in-need specialties are sometimes out of their control.

Medicaid’s low reimbursement rates for pediatricians and other primary care physicians can make it challenging for some practices to retain staff and provide needed care for patients.

In Virginia, the result is that more than 60% of open physician roles are for primary care positions, and those are concentrated in metro areas, likely due to patients’ ability to pay rather than need for physicians, according to a preliminary study issued in 2023 by the Virginia Health Workforce Development Authority.

Nationally, during the past 10 years, family medicine has had the lowest number of residency program slots filled within primary care specialties.

But in some cases, political and social factors — such as health care policies and growing awareness of the social determinants of health — are in part prompting students to chase specialties with great need for doctors, says Dr. Arturo Saavedra, dean of the VCU School of Medicine and VCU Health System’s executive vice president for medical affairs.

One example is Swet Patel, a fourth-year U.Va. medical student who has chosen family medicine as his specialty. Patel says seeing how overworked physicians were in larger institutions led him to want to own his own independent practice so he could have greater autonomy.

Dhaliwal, the fourth-year U.Va. medical student pursuing psychiatry, says she was drawn to the intersections of race, class and gender that “come to light” in psychiatry after working closely with

social workers.

But despite the urgent need for psychiatrists and family physicians, there’s a cap on the number of federally funded residency positions — which means there could be interest but not enough spots for them.

“We need more doctors in this country,” Dhaliwal says, “and they make it so hard.”

s