Everything is not awesome

Why Virginia lags the South in big industrial deals

Everything is not awesome

Why Virginia lags the South in big industrial deals

When Lego Group representatives toured Chesterfield County’s Meadowville Technology Park on a winter day early this year, they didn’t speak.

As with most industrial site visits, the county economic development authority staffers conducting the tour didn’t yet know which company they were working with, although they’d answered a site consultant’s request for proposal. The execs from the Billund, Denmark-based toymaker sought to keep it that way, avoiding revealing their Danish accents by letting their consultants do the talking.

“They told us later on, ‘The day we saw the site, we knew it was where we wanted to build. It was instant,’” recalls Chesterfield Economic Development Director H. Garrett Hart III.

In June, Lego held a festive news conference with Virginia Gov. Glenn Youngkin, announcing the company’s plans to build a $1 billion manufacturing plant on 340 acres at Meadowville to turn out its brightly colored toy bricks.

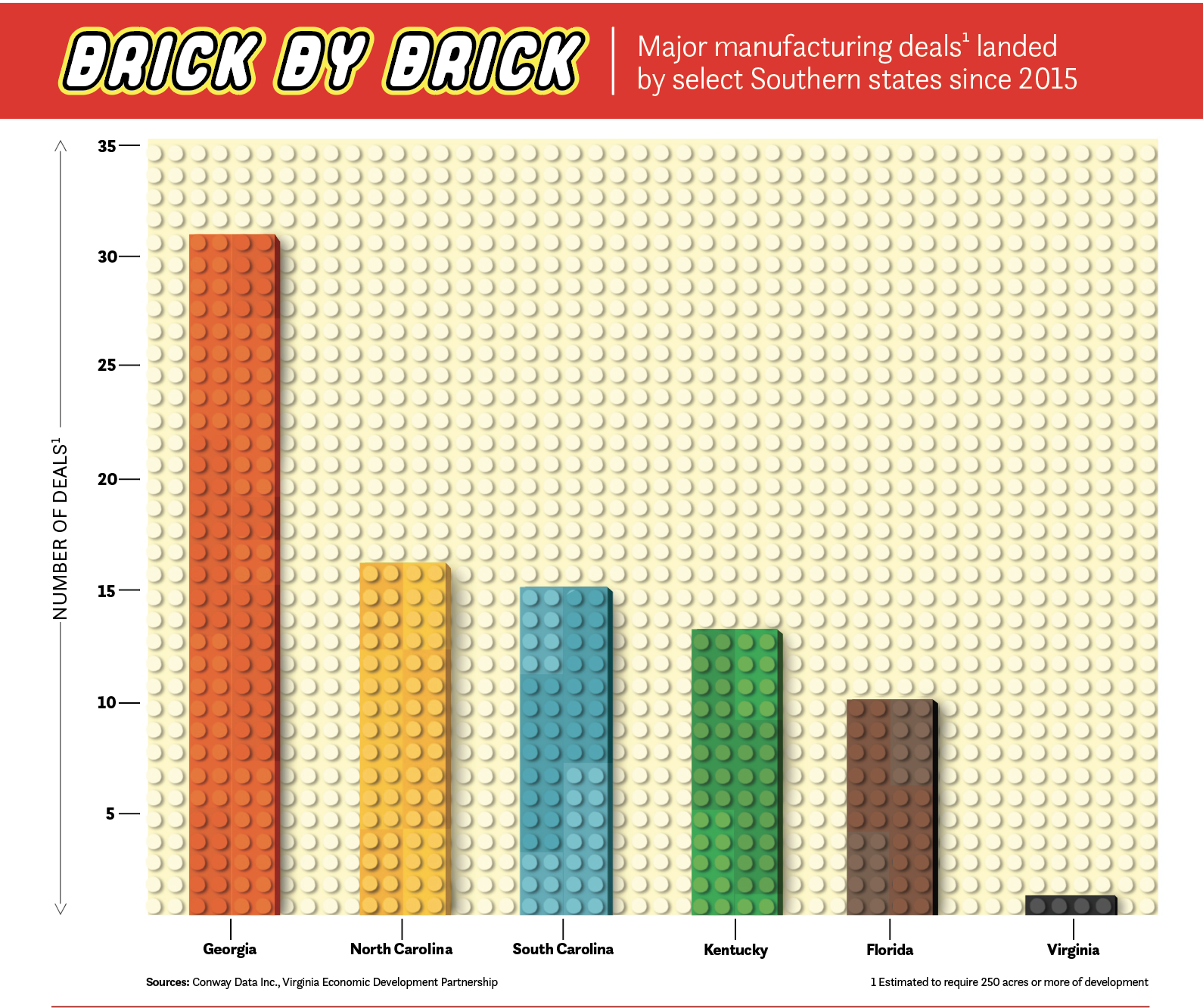

The problem? Despite local and state efforts at marketing industrial sites in the commonwealth, the Lego factory is the only manufacturing project requiring an estimated 250 or more acres that Virginia has landed in the past seven years.

From January 2015 through September 2022, 121 new industrial projects requiring an estimated 250 or more acres were announced in the Southeast, according to the Virginia Economic Development Partnership. Combined, those projects generated more than $25 billion in capital expenditures and an estimated 58,000 jobs.

And Virginia won just one: Lego.

The commonwealth’s shortage of large, project-ready sites is the largest deterrent to Virginia landing these projects, economic development officials say.

Industrial megaprojects are worth competing for, says VEDP President and CEO Jason El Koubi: “If we want to achieve Gov. Youngkin’s goal of [creating] 400,000 jobs over his four-year term, if we want to position Virginia as a job growth leader, winning the big projects is critical.”

As of August, nearly 100,000 more Virginians were employed than at the end of January, when Youngkin began his term, figures that can be attributed partly to pandemic recovery. Even so, Youngkin, a former co-CEO of Washington, D.C.-based private equity firm The Carlyle Group, has said that he thinks the commonwealth has a long way to go in economic development — even as Virginia held the top ranking in CNBC’s Best State for Business report in 2019 and 2021 and currently ranks No. 3. (See related Youngkin interview)

Big sites have big payoffs. Between 2018 and 2021, large projects requiring 250 acres or more comprised 15% of companies’ site-search requests in Virginia but accounted for 51% of potential jobs and 78% of potential capital expenditures, according to VEDP.

Manufacturing projects also matter for small metro areas and rural regions of Virginia.

“For many regions of Virginia,” El Koubi says, “manufacturing projects represent the single largest industry sector by jobs of their announcements over the last five years. Winning in manufacturing and other industrial sectors is critical for the economic growth and vitality of many of Virginia’s regions.”

Virginia has reliably secured projects in the so-called “golden crescent” stretching from Northern Virginia south to Richmond and Hampton Roads but needs to diversify its economic development into other areas, says Gentry Locke Consulting President Greg Habeeb, a Republican former state delegate who represented Roanoke. Habeeb, who now represents companies exploring economic development deals in the commonwealth, would like to see Southwest or Southern Virginia land a car manufacturer or another project comparable to Lego.

“We have large swaths of Virginia with very talented workers, with low cost of living … where we have not been as good at landing the really big projects. That to me is kind of the next phase,” he says.

The lay of the land

Manufacturers’ decisions on where to locate are multifaceted, but site availability is the first step.

“If you didn’t even have the sites, then you couldn’t be out there doing your permitting activity, getting your utilities ready,” says Chris Lloyd, McGuireWoods Consulting LLC’s senior vice president of infrastructure and economic development.

“One of the most common reasons that Virginia has been eliminated [in the selection process] for large manufacturing projects is because we do not have an inventory of very large sites of sufficient readiness to meet the needs of those projects,” El Koubi says.

Virginia’s largest VEDP-certified site — those ready for construction in 12 to 18 months — is the Southern Virginia Megasite at Berry Hill, owned by the Danville-Pittsylvania County Regional Industrial Facilities Authority. Of the site’s 3,528 acres, about 1,900 are easily developable. The site has water, electricity and sewer infrastructure, and construction on a connector road will start in January.

Although Virginia economic development officials pitched the site to Hyundai Motor Co. executives, Hyundai selected a location near Savannah, Georgia, for its $5.5 billion electric vehicle and battery manufacturing plant. Announced in May, it’s expected to create 8,100 jobs.

“We had a 2,200-acre megasite. Even though it wasn’t pad-ready, all the due diligence and the zoning had been complete. That’s a big, big thing that companies are looking for, especially [for] megaprojects like this, where time is everything,” says Hugh “Trip” Tollison, president and CEO of the Savannah Economic Development Authority, part of the joint development authority that acquired the Georgia site for $60 million in 2021. The authority started work on due diligence, zoning, wetland impact studies and other necessary prep for the site about eight years ago, completing it ahead of the acquisition.

Including the Berry Hill site, VEDP lists only six certified sites with 250 or more acres in Virginia, two of which are privately owned, and only two sites of 1,000 or more acres. The Southern Virginia Megasite is the only property of those six that VEDP lists as pad-ready — graded and ready for the development of flat parcels that can support construction — in its site database. So far, 200 acres of the Southern Virginia site have been graded, and another 65 acres are under development.

A farmland property in Chesapeake could become another 1,000-plus-acre site, but it’s currently privately owned and zoned for agriculture. In 2017, property owner Frank T. Williams proposed the city create a 1,420-acre megasite there — the Coastal Virginia Commerce Park. As of September, an application to rezone the land was set to go before the city planning commission in November. Chesapeake City Council in 2018 approved an amendment to the city’s comprehensive plan to allow for the park. Council must sign off on the rezoning application in order for the Chesapeake Economic Development Authority to purchase the site and begin development.

Public ownership is a major competitive advantage, as manufacturers are focused on speedy approvals and construction.

“The essential question throughout the last six years was, ‘Well, it’s a great site, but you don’t own it.’ And we said, ‘Yeah, you’re right. We don’t own it,’” says Tollison with Savannah’s EDA. “And until we really owned the site and could control our own destiny, it was a difficult proposition to convince a company like Hyundai to come to a site that we didn’t own.”

In contrast to Virginia, North Carolina has four sites available that are larger than 1,000 acres. The state realized it needed to develop sites to compete for megaprojects about 15 years ago, says Christopher Chung, CEO of the Economic Development Partnership of North Carolina (EDPNC).

“There were a lot of these automotive assembly plants that were announced in the late ’90s through probably [the] mid part of the 2000s,” he explains, “and during that stretch, we just did not have a good site that was under control, assembled, optioned [and] had design and engineering — if not actual infrastructure — extended to them, and other states did.”

North Carolina’s state legislature authorized a site-readiness program but didn’t always allocate funding to it. Nongovernmental agencies, like the Joseph M. Bryan Foundation of Greater Greensboro and the Golden LEAF Foundation, which administers tobacco settlement agreement funds to North Carolina’s rural and economically distressed areas, filled gaps.

In December 2021, Toyota announced it would build a $1.3 billion electric vehicle battery manufacturing facility, expected to generate 1,750 jobs, at North Carolina’s Greensboro-Randolph Megasite. In August 2022, Toyota announced an additional $2.5 billion capital investment in the project, adding 350 jobs.

North Carolina’s western neighbor also joined the race to land manufacturing megaprojects years ago. In 2009, Tennessee purchased 4,100 acres of former farmland that became the Memphis Regional Megasite. By the time it landed a project in September 2021, the state had invested at least $174 million into developing the site.

Its new tenant is a joint venture between Ford Motor Co. and SK Innovations for a $5.6 billion, 3,600-acre electric truck and EV battery plant, which will create a projected 5,600 jobs.

Below the curve

Why are these states lapping Virginia? It comes down to funding and priorities.

Virginia has historically made much smaller investments in site development than its neighbors.

Manufacturing megaprojects weren’t always a priority for Virginia, says Lloyd with McGuireWoods. “I think some of it was, we enjoyed several decades of success with economic development projects, and maybe we weren’t as focused on that as other places,” he says. “We were seeing the big office projects, the Northern Virginia economy was humming along and … we weren’t as diligent as some of the other states in order to pursue those.”

In 2021, the Virginia General Assembly allocated $5.5 million for the Virginia Business Ready Sites Program (VBRSP), a discretionary VEDP program that provides grants to localities for site characterization and development. But in previous years, the state dedicated about $1 million to the fund annually. It’s difficult to calculate the cost of developing Virginia’s sites, El Koubi says, as VEDP has only preliminary information for some sites, and the VBRSP wouldn’t bear some costs, like utility infrastructure.

In comparison, Tennessee this year announced nine site development grants that totaled about $7.6 million. In 2021, Tennessee awarded almost $12.8 million in these grants. North Carolina’s Golden LEAF Foundation budgeted $15 million for its site development program this fiscal year.

However, Virginia’s 2022-24 state budget, signed into law in June, included a historic $159 million for the VBRSP to support site development. In former Gov. Ralph Northam’s outgoing budget, he proposed the program receive $150 million. While campaigning in 2021, Youngkin said he would support shifting $200 million in federal stimulus funding toward improving site readiness.

Among the VBRSP’s goals are providing localities with grants to develop new, “high-win potential sites” — properties that can support market demand and are expected to land a big project within 18 months of becoming project-ready. In September, VEDP began reviewing localities’ site-development grant applications. VEDP expects to announce awards in January 2023.

This is not a one-and-done solution, however. Virginia needs to continue allocating funds of this magnitude to site readiness in order to be competitive, El Koubi says.

To the south, North Carolina is chugging ahead on further development. In its budget signed in July, North Carolina launched a megasite fund with an initial $1 million for EDPNC to work with a site selection consulting firm to identify the state’s next megasites. Next year, EDPNC will present up to five potential sites to the legislature for development funding.

A more nebulous problem for Virginia is how it’s perceived by potential investors.

Although the commonwealth’s competitors know it isn’t the case, company executives might not see Virginia as a manufacturing state, North Carolina’s Chung says. “I just know being kind of next door to Virginia for eight years, Virginia’s perception in the market does tend to be heavily dominated by Northern Virginia,” which is driven by the defense contracting and technology sectors.

El Koubi acknowledges the same issue. “I would say that there’s a gap between the reality of Virginia’s strengths as a manufacturing state and the perceptions of Virginia, in part because of the underinvestment in marketing.”

VEDP’s current annual economic development marketing allocation, excluding tourism, is $2.7 million. Meanwhile, in June 2021, VEDP’s North Carolina counter-part launched a $3 million national advertising campaign focused on business recruitment. The EDPNC is set to receive $10 million each year for the next three fiscal years to continue the campaign.

Pittsylvania Economic Development Director Matthew Rowe agrees that companies’ perceptions of Virginia have been slow to change. “I think Virginia’s just now getting into the megasite game,” he says. “I think when a big company’s like, ‘I need a megasite,’ they’re automatically thinking of North Carolina, Kentucky, Tennessee, Georgia, Alabama.”

Gaining recognition and credibility once a state has a site takes time.

While having dinner with one company’s representatives, Rowe asked why they were looking at other Southeastern states when the Southern Virginia Megasite was closer to their customers. They answered that, in the eyes of their board, states that had recently won large projects must be doing something right.

But about 12 months ago, as its site-readiness advanced, the Pittsylvania site began receiving more interest, Rowe says.

Although he’s tight-lipped about the names of interested companies, Rowe hints that the Southern Virginia Megasite could land a deal comparable to Lego: “We literally do helicopter tours probably once a month with name-brand companies that most people would recognize.”

g