History in the making

Colonial Williamsburg emerges revitalized from pandemic

History in the making

Colonial Williamsburg emerges revitalized from pandemic

Cliff Fleet took the helm of the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation in January 2020 with a mandate to curb declining attendance and revenue at the nation’s largest outdoor living museum while maintaining its relevance to diverse 21st-century audiences.

It was a tall order and one that became even more challenging two months later when the COVID-19 pandemic forced Colonial Williamsburg to shutter properties within its 301 acres for three months. Meanwhile, the nation became engulfed in social and political unrest, with debates erupting over how to present a more complete narrative of the events and people that shaped the nation, including those in Colonial Williamsburg.

“It’s been an interesting year,” reflects Fleet, a William & Mary alumnus and former president and CEO of Richmond-based tobacco manufacturer Philip Morris USA. “Obviously, we could not predict how the pandemic and social justice movement would unfold, but we made sure our focus was on the health of our employees, guests and the region as we thought about how to reopen safely and soundly.”

Colonial Williamsburg has a massive economic impact on Williamsburg. The private, nonprofit foundation oversees more than $1 billion in assets, including the living history attraction, museums, lodging and restaurants. It’s the city’s second-largest employer, next to William & Mary. The foundation owns approximately 300 properties within the city limits and about 25 more in James City and York counties.

Fleet was hired to replace Mitchell B. Reiss, who stepped down as the foundation’s eighth president and CEO in October 2019 at the end of his five-year contract. Reiss oversaw a series of dramatic cost-cutting measures at the foundation, which has had to contend with declining attendance and revenues in recent decades. Visitation at the nearly 100-year-old living history tourist attraction has dropped from 960,000 in 1999 to 534,000 in 2019. The 2010s saw the foundation making large draws from its endowment to balance its books.

So, Fleet, who holds a law degree and graduate degrees in history and business administration from William & Mary, was already prepared to enter a challenging leadership role. But then came the coronavirus pandemic.

21st-century engagement

Although Colonial Williamsburg’s hospitality staff were furloughed during the pandemic, Fleet says, the foundation made sure their health insurance benefits were maintained, and food from closed Colonial Williamsburg restaurants was used to provide tens of thousands of meals to the community.

And activities at the historic site did not grind to a halt during the closure. The foundation used the down time to spruce up landscaping and buildings and accelerate work on projects that tell a more balanced, complete story of Colonial life.

Additionally, Colonial Williamsburg used the pandemic to expand its digital presence. The foundation launched a streaming channel on Amazon Fire TV and Roku in early April 2020. It also enhanced its online educational content, including blogs, video and virtual tours, allowing visitors from all corners of the globe to virtually travel to the historic site. Colonial Williamsburg’s online content received more than 13.5 million video views and nearly 110 million digital impressions last year.

“We’ve seen great growth over the past year in means that don’t involve physically having visitors here to deliver educational programs,” Fleet says. “It’s heartwarming to see how many people we have reached through our digital footprint.”

More than a year after the pandemic began, Colonial Williamsburg has reopened the larger buildings in the historic area and moved other programs outdoors. It’s also launched new and expanded historic interpretation programs, including relating more stories of women and Black people and American Indians who lived and worked there in the 18th century.

“Colonial Williamsburg is set to emerge from the pandemic stronger than when it began,” says foundation spokesman Joseph Straw. “As a harbinger of good things to come, visitation is building back up as we enter spring.”

Meanwhile, the foundation is coming off a successful fundraising year, including raising a record $19 million designated for its unrestricted Colonial Williamsburg Fund.

All of which puts Colonial Williamsburg Foundation on more solid footing as the organization prepares to celebrate its own centennial and the 250th anniversary of the signing of the Declaration of Independence in 2026. “We’ve built a plan to help strengthen our financial profile as we approach 2026,” Fleet says. “We’ve made good progress and are excited about where we are.”

Not dry and dusty

Colonial Williamsburg strives to ensure its programs are both engaging and relevant, Fleet says, especially as it relates the intersection of current events with the past. “We’ve learned people are very interested in what we do, but we need to be very thoughtful about how we do it,” Fleet says. “We’re continuing to evolve and add experiences that tell a more full, inclusive story.”

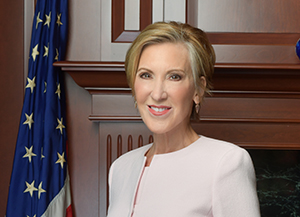

Telling Colonial Williamsburg’s story in an accurate, complete, inclusive and compelling manner is one of Carly Fiorina’s goals as chair of the foundation’s board of trustees. Elected chair last December, the onetime GOP presidential hopeful and former CEO of Hewlett-Packard Co. says she’s using her industry experience to support the foundation’s continued digital evolution and delivery of more inclusive programming.

“Sometimes the word ‘history’ is interpreted as dry, dusty, academic, but most people respond to the human story,” she says. “When you can connect to a human being telling a story about a real person, and the person is surrounded by objects and events, that’s very compelling.”

Fiorina adds that Colonial Williamsburg seeks to be world-class in its threefold mission of preservation, education and civic engagement as it reaches out to a more diverse audience. “We realize our true, complete history is much bigger than Jefferson, Madison and Washington, although they are an incredibly important part of our history,” she explains. “History also includes the unsung heroes.”

Heroes like the people who founded Williamsburg’s First Baptist Church in 1776. One of the oldest American continuous congregations established by Black people, First Baptist’s original building was demolished in the 1950s and the site was later paved over for a parking lot. Last year, Colonial Williamsburg, in partnership with the church, began excavating the original site, unearthing brick foundations and structural wooden postholes dating as far back as the 1700s. A second phase of the archaeological project began in January.

Colonial Williamsburg also is working with William & Mary to relocate the Bray-Digges House from the college’s campus to the Historic Area. The building once housed the Williamsburg Bray School, an 18th-century institution that educated enslaved and free Black children. The Bray-Digges House will be the 89th restored, original structure housed in the Historic Area.

“Both First Baptist Church and the Bray School are really important to our nation’s history,” says Fleet. “We always have more history to uncover and more history to go back and rethink and reanalyze.”

Those projects also will help Colonial Williamsburg reach a broader audience, Fiorina adds. “That work is intensively interesting to people who might have thought Colonial Williamsburg was about a bunch of guys walking around with pointed hats and fifes and drums and that was it.”

Inclusive history

Describing the historic site’s mission, Colonial Williamsburg benefactor John D. Rockefeller Jr. coined the foundation’s motto, “That the future may learn from the past.”

“That continues to guide all our work,” Fleet says. “We constantly challenge ourselves to continue to build on that rich heritage.”

Colonial Williamsburg’s Historic Area, which started offering historic reenactors in the 1930s, began interpreting Black characters in 1979 and has also included portrayals of American Indians. A recent virtual presentation, “Created Equal,” highlighted Black perspectives on the American Revolution.

Stories from the 1700s are relevant to 21st-century events, adds Beth Kelly, Colonial Williamsburg’s vice president for education, research and historical interpretation. “The past year gave us more insights into our audience and their capacity and desire to understand the depth and breadth of this 18th-century community,” she says. “The pandemic irretrievably changed our lives. The same thing happened to this 18th-century community with political impacts. Each member saw it differently. Those are the stories we want to tell.”

While interpreters previously relayed mostly rote information, such as dates and details about Colonial furniture and architecture, they now frequently step out of character to contextualize a scene, allowing visitors to ask questions and dig deeper. For example, Kelly explains, modern audiences can be uncomfortable watching a vignette between a Black enslaved woman and her white mistress. “It’s not easy to portray enslaved and enslavers,” she says. “When they come out of character, guests can understand the tension. That opens the conversation and allows us to understand the roots of what we experience as Americans.”

Colonial Williamsburg also has begun exploring the role of LGBTQ people in early America. “They certainly did not live within the accepted boundaries of the 18th century, but they were definitely there,” Kelly says. The initiative has received an overwhelmingly positive response from the LGBTQ community.

“We’re not trying to change any part of the story of the 18th century,” she adds. “We’re just trying to ensure the whole story is told. When we look at the whole picture and understand all the threads that make us up as a community, it makes it much more vibrant and interesting.”

Back to the future

Philanthropy has played a critical role in advancing Colonial Williamsburg’s mission, especially during the pandemic. The foundation’s 2020 annual fundraising netted $62 million. “We have a very loyal donor following that recognized that this was a challenging year for all museums,” says Colonial Williamsburg’s chief development officer, Earl Granger. “Our donor community answered the call in some really significant ways.”

The foundation’s $600 million Campaign for Colonial Williamsburg concluded in December 2019. It included $163.5 million for updated programming and research initiatives and a $42 million expansion of the DeWitt Wallace Decorative Arts Museum and the Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Folk Art Museum. “Philanthropy supports Colonial Williamsburg’s core education mission,” Granger notes. “It lends itself to our best ideas and allows us to invest in people, programs and services to bring world-class services.”

Strengthening the foundation’s endowment, as well as reducing the amount and cost of debt, are among Fleet’s priorities as Colonial Williamsburg prepares for its 2026 centennial. Last year, the foundation sold its 200-room Governor’s Inn to Charlottesville real estate investment company Castle Development Partners LLC for $3.05 million. The property is slated to be developed into an apartment complex.

The foundation also hopes to expand the 18th-century-style retail village Merchants Square to the south, adding a mix of residences, retail and office space. Another project, about a half mile away, would transform the nine-hole Spotswood Course at Golden Horseshoe Golf Club into a walkable residential neighborhood.

“We want to increase the appeal and livability of downtown Williamsburg,” Fleet says. He adds that the foundation is working with local authorities to determine the best uses for its numerous properties throughout Williamsburg and the Upper Peninsula.

A walkable new neighborhood near Merchants Square would be advantageous to local businesses, adds Williamsburg Mayor Doug Pons, who acknowledges opposition to the move from the Spotswood Senior Golf Association, golfers mostly age 70 and older. “Spotswood is iconic, but not everything should last forever, and Colonial Williamsburg still maintains two 18-hole golf courses.”

A regional government task force identified the Colonial Williamsburg Visitor Center’s 100-acre campus as a potential site to locate a proposed community sports complex. The visitor center would remain on the large site, most of which is now vacant and devoted to parking lots and 20th-century buildings that are no longer in use. Colonial Williamsburg supports the proposal.

A sports complex would invigorate both the town and Colonial Williamsburg, Pons adds. “Williamsburg is ripe for this kind of investment. It could be a financial draw for Colonial Williamsburg.”

In the interim, though, Fleet is focused on ensuring more people immerse themselves in 18th-century Virginia. “Colonial Williamsburg is an incredible place,” Fleet says. “It’s an incomparable platform used to understand our culture and history and help us discern the issues of today.”